A relative pronoun is a word that we use to combine two sentences (or more) into one sentence without having to repeat the word that is common to both sentences. For instance the sentences

Where is the book? I was reading the book last night.

can be combined into one sentence that runs

Where is the book that I was reading last night?

The part of the sentence that contains the word “that” is called the subordinate clause, and the other part of the sentence is called the main clause. The word “that” is called a relative pronoun. The phrase “the book” in the main clause we call the antecedent of the relative pronoun.

English has other words besides “that” that can serve as relative pronouns, e.g. which, who, whom, and whose. For instance:

I would like to return this parrot, which I bought in this very shop not half an hour ago.

She knows a man who speaks four languages.

The woman with whom you were seen yesterday is a spy.

One of the interesting things about English is that sometimes we can use a zero-form for the relative pronoun; that is, both of the following sentences are possible:

(1) Where is the book that I was reading last night?

(2) Where is the book I was reading last night?

In Russian one cannot leave out relative pronouns. That is, any time you are translating a sentence like (2) from English to Russian, you will first have to rephrase it as (1) to get it right.

English sentences with relative pronouns can often end in a preposition:

(3) I want to buy the book that you were talking about.

Russians never end sentences with prepositions, so any time you are translating a sentence like (3) from English to Russian, you will first have to rephrase it as (4) to get it right:

(4) I want to buy the book about which you were talking.

Relative clauses most commonly occur at the end of the sentence, but they can also occur in the middle of a sentence, for instance

The book that I was reading last night is really interesting.

In this case the sentence “I was reading the book last night” is embedded as a relative clause in the middle of the sentence “The book is really interesting.” Russian also can have relative clauses either at the end of a sentence or embedded in another sentence.

There are several words that are used as relative pronouns in Russian, and the one we want to address today is который. It's endings are like any other perfectly regular adjective of the новый type:

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Plural | |

| Nom | который | которое | которая | которые |

| Acc | * | которое | которую | * |

| Gen | которого | которого | которой | которых |

| Pre | котором | котором | которой | которых |

| Dat | которому | которому | которой | которым |

| Ins | которым | которым | которой | которыми |

| * copies nom. if inan.; copies gen. if anim. | ||||

Let's say we want to write in Russian “Where is the book that I was reading yesterday?” That will come out something like this:

Где книга, котор_____ я вчера читал?

We must figure out which ending to put in the blank. The easiest was is to break the sentence down into two simple sentences:

| Main clause | Subordinate clause |

| Где книга? | Я вчера читал книгу. |

Here's the rule for figuring out который:

Который takes it's gender, number, and animacy from the noun it refers to in the main clause (in other words, its antecedent), and it takes its case from the grammatical role it plays in the subordinate clause.

In this case the antecedent is книга in the main clause, which is feminine singular. In the subordinate clause книгу is the direct object of the verb читал, and therefor it appears in the accusative case. Combining those features, we deduce that the proper ending for котор_____ in this instance will be feminine singular accusative, which from the chart we see is -ую. The final form of the sentence is

Где книга, которую я вчера читал?

Here is another way to picture it diagrammatically:

Note that the gender and number of котор_____ comes from the word it refers to in the main clause, but its case comes the role it's playing in its own clause, which in this case is accusative because it is the direct object of the verb читал.

Let's try another example. Let's say we want to say “I want to buy that magazine she was talking about.” Since the sentence ends in a preposition, we need to rephrase it in more formal English to set up the Russian sentence. Thus we will base our translation on “I want to buy that magazine about which she was talking.” This gives this almost complete Russian sentence:

Я хочу купить тот журнал, о котор_____ она говорила.

To do our analysis we will break it down into two sentences:

| Main sentence. | Subordinate sentence. |

| Я хочу купить тот журнал. | Она говорила о том журнале. |

Since который takes it's gender from the phrase it refers to in the main sentence, we take the features masculine and singular from тот журнал in the main sentence. Since который takes its case from the role it plays in its own clause, we take prepositional case from том журнале in the subordinate sentence. Combining them, we achieve the final form:

Я хочу купить тот журнал, о котором она говорила.

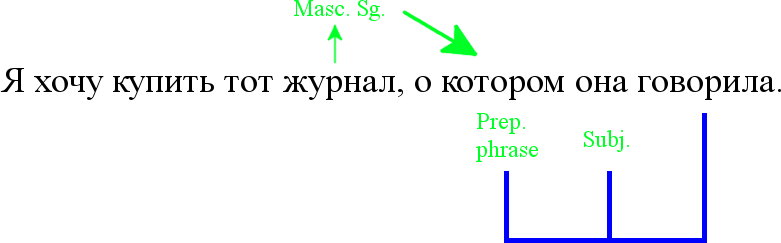

Let's look at that sentence diagrammaticaly:

Note that the gender and number of котор_____ comes from the word it refers to in the main clause, but its case comes the role it's playing in its own clause. In the subordinate clause the verb говорила is taking a prepositional phrase as its complement. The preposition is «о», which governs the prepositional case when it has the meaning of “about.”

Let's take a more complex sentence now: “What is the name of the boy you were reading the story to last night?” Since the preposition “to” is refering to “the boy,” we see that it is one of those tricky displaced prepositions that English uses so often. This means we will have to rephrase the sentence into more formal English, thus “What is the name of the boy to whom you were reading last night?” Thus our partial Russian sentence will thus be

Как зовут мальчика, котор_____ вы вчера читали рассказ?

Breaking the sentence down into two sentences, we get

Как зовут мальчика? Вы вчера читали мальчику рассказ.

There is a bit of a trick here. In English we can say either “You read the boy a story,” in which case “boy” is an indirect object, or we can say “You read a story to the boy,” in which case boy is the object of the preposition “to.” The Russian verb читать does not allow the option of using a prepositional phrase: the person to whom you read must be an indirect object.

Since который takes it's gender from the phrase it refers to in the main sentence, we take the features masculine and singular from мальчика in the main sentence. Since который takes its case from the role it plays in its own clause, we take dative case from мальчику in the subordinate sentence. Combining them, we achieve the final form:

Как зовут мальчика, которому вы вчера читали рассказ?

Now let's look at it diagramatically:

To summarize, then, the key to making который work is to methodically identify the antecedent, from which который takes its gender, number, and animacy; and to identify the grammatical role it is filling in its own clause.