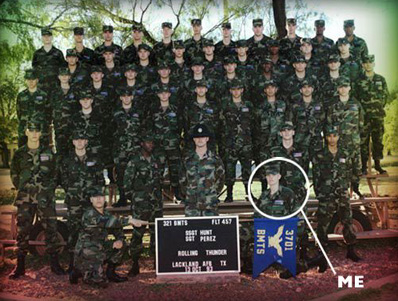

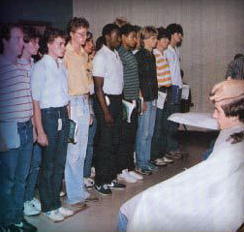

Confusion was the first gripping emotion that overtook us. It was definitely an emotion sprinkled with pains in our gut and our temples as we tried to shake the departure from our families. This was our first whole day at Lackland. The moment that found us so confused was the second after which we each stood up from the maniacal barber’s chair and caressed the nothingness now situated on our scalps. Shaving every follicle from our heads was the barber’s job. Adapting to their work was ours. It was the equalizing template for all newly arrived airmen. The lack of hair resonated throughout the waves of us so that, when in marching formation, the flight resembled a sea of troughs and glistening, cloned caps. That appearance, coupled with our now unacceptable civilian attire, gave reason for all attending drill instructors to label us as “rainbows”. That would last until each of us marched in those crisp, pungent battle dress fatigues with sixty-pound, stuffed duffle bags over our aching shoulders.

The early 1990’s witnessed the birth of a

popular phrase to reference the U.S. military’s operational

practice in dealing with homosexuals. This was the “don’t ask, don’t

tell” policy. Widespread aversion to the idea of gays in the military

allowed the policy’s phraseology to be more of a punch line than a serious

solution. This was the coming out of sexual America. Everyone

was touched by the possibility of a seemingly volatile sect of society breaking

into the mainstream. The military was no different. I found myself

in the midst of a microcosm while serving out a six-week basic training assignment

at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas. The bald headedness

around me was supposed to buffer differences. They were supposed to

erase mentalities of persecution. We were to change from a rambling

group of preconceived notions into an unfailing squadron of comradery.

At first, such was not the case.

The early 1990’s witnessed the birth of a

popular phrase to reference the U.S. military’s operational

practice in dealing with homosexuals. This was the “don’t ask, don’t

tell” policy. Widespread aversion to the idea of gays in the military

allowed the policy’s phraseology to be more of a punch line than a serious

solution. This was the coming out of sexual America. Everyone

was touched by the possibility of a seemingly volatile sect of society breaking

into the mainstream. The military was no different. I found myself

in the midst of a microcosm while serving out a six-week basic training assignment

at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas. The bald headedness

around me was supposed to buffer differences. They were supposed to

erase mentalities of persecution. We were to change from a rambling

group of preconceived notions into an unfailing squadron of comradery.

At first, such was not the case.

Despite his warmth, noble convictions, and empathy toward fellow airmen, the sons of thirty-some states throttled Pinkerschmidt to exhaustion. It was perhaps the fact that he chose to listen. Maybe it was his attention to cleanliness, which, in basic training, is definitely a virtue. Nevertheless, Pinkerschmidt’s ordeal was one of a sexual borderland. While he went day-to-day in the same stale uniforms as the rest of us, clutching crinkled letters from home like the rest of us, and sobbing after a phone call home with the rest of us, Pinkerschmidt felt the brunt of a nation’s children in sexualized turmoil.

“Pinky”, as he was labeled, stood about five-foot-eight, from the edge dressing on his boots to the stubble on his head. He had a small paunch about the waistline that seemed to echo the protruding lips on his otherwise narrow facial features. The uniform was the same. The salute was the same. Even the dust-bunnies that took up residence beneath his drab, grey bed was just like the rest of ours. In all apparent accounts, Pinky was just another one of the guys. As time went on, Pinky found himself laughing along with the jokes at his own expense. That was the kind of guy he was at first. The words that befouled him were sent out like jokingly, innocent gestures surrounding his manhood. I can only relay this as I see myself acting in his situation. That is to say I felt his pain and helplessness in the face of outnumbering critics.

The floors of the barracks were as shiny as our foreheads

after a morning run. They seemed clean and untarnished by the atrocities

that mounted upon them. Pinky was in regular spirits with regard to

his abnormal existence in such a persecuting realm. I had found a quiet,

but congenial, distance from him if only because we had no pertinent shared

interests at the time. He kept folding his underwear and tightening

the wool blanket on his bed as the daggers of sexual incongruity stuck to

his back. There were no visible signs of aggression from his disposition

for the first four weeks or so. Our drill instructor certainly had no

idea what kind of torment soiled the sanitized halls in which he ruled all

knowing. One particular line of bunks was more incontinent than the

rest. They generally saw fit to capitalize on the nation’s fear of

gays by laughing out their puns of Pinky’s worst like hot water on the shower

floor. He bent to unlock his footlocker. The jokes ruptured.

He crouched to fiddle its contents. The jokes echoed. He heaved

at the bequest of his fatigued patience. The jokes found time to pause.

Pinky stood straight up, tears running down his five o’clock shadow and across

his quivering chin. There was silence.

The floors of the barracks were as shiny as our foreheads

after a morning run. They seemed clean and untarnished by the atrocities

that mounted upon them. Pinky was in regular spirits with regard to

his abnormal existence in such a persecuting realm. I had found a quiet,

but congenial, distance from him if only because we had no pertinent shared

interests at the time. He kept folding his underwear and tightening

the wool blanket on his bed as the daggers of sexual incongruity stuck to

his back. There were no visible signs of aggression from his disposition

for the first four weeks or so. Our drill instructor certainly had no

idea what kind of torment soiled the sanitized halls in which he ruled all

knowing. One particular line of bunks was more incontinent than the

rest. They generally saw fit to capitalize on the nation’s fear of

gays by laughing out their puns of Pinky’s worst like hot water on the shower

floor. He bent to unlock his footlocker. The jokes ruptured.

He crouched to fiddle its contents. The jokes echoed. He heaved

at the bequest of his fatigued patience. The jokes found time to pause.

Pinky stood straight up, tears running down his five o’clock shadow and across

his quivering chin. There was silence.

“Listen to me you assholes. I don’t give a damn where you’re from or who you’ve slept with. I’ve watched you cry when you got off the phone with your girlfriends or your families or at the news of your dying dog. I’ve put up with your crap everyday that I had to mop that damn latrine, and still you call me a fag and a fairy and all the other foul names you could come up with. You all forgot about the picture I carry in my wallet of a seventeen year old girl that I love back home. You all forgot that I was still planning on marrying her. You all forgot not to ask and not to tell. I’m no different than you. And I sure as hell don’t care if you’re gay or not.”

Nobody laughed. Nobody smiled. Somebody dropped their dog tags on the floor, and then I think we all looked inward. It wasn’t the words that rolled so poetically fierce off of Pinky’s bowed lips. It was the sudden break in the silence afterwards that caught our attention. That was the moment, that cataclysmic moment, when so many of us realized that we had been stopped in our tracks by the plight of one of us. He was the other and he wasn’t the other. We made him and forgot him and suddenly remembered him. What had begun four weeks prior, in the seat of a burly, grey barber and hair falling around us like memories, in complete confusion, had just become the singular moment of clarity. Pinky blew up and we all stood there with our eyes at the floor and our jocks in our throats. What the hell had we done? Who in the hell had we turned that kind, understanding kid into? While religions blasted same-sex relationships and protests waged against their communion, hell and hatred had defined the borderland for us that year.