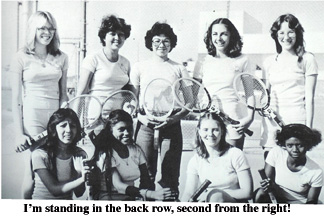

I distinctly remember when I learned that there is another way. When I was a sophomore in high school I played on my high school’s Junior Varsity tennis team. I was a pretty good player, I thought, and I really enjoyed it. We played half of our scheduled matches at “home”, on our own campus, and half “away” on the competitor’s campus.

We played one of our matches at

Camelback High School in central Phoenix. We took the school van

across town to the Camelback campus. I always hated taking the

van because it made me carsick. It was a great day in February,

the air was a little warm but there was a cool breeze and lots of

sunshine. I was looking forward to playing on Camelback’s tennis

courts because they seemed like “real” courts. They had cloth

nets, whereas Carl Hayden’s were made of fencing to avoid

vandalism.

At the time, Camelback High was considered “rich” and consisted of nearly all white kids. The girls on their tennis team had cute tennis outfits, pure white with matching bloomers. Ours were old and worn and most didn’t fit properly. Of course, the reality is none of this should matter. We were there to compete. But it did matter. All of my team mates were Hispanic and with my dark hair and eyes, the Camelback players assumed that I, too, was Hispanic. They showed an obvious, palpable disrespect toward my team. Humiliating glances, disrespectful giggles, and unfriendly attitudes were everywhere.

Carl

Hayden? Oh, man! I hate playing Carl Hayden’s tennis

team! First of all, it’s not really even like playing a tennis

match. None of them are that good so it’s hard to get a decent

volley going. Plus, they’re all punks. Who knows if they’re

bringing their boyfriends or they’re going to want to start

something. At least we don’t have to play at their school!

That would be awful having to drive to that side of town for a quick 10

minute blow out match. What if something happened while we were

down there?

Here they come in their team van. Oh God…look at their uniforms. How embarrassing! They’re not even all the same shade of white. Some look yellowed. Some girls aren’t wearing the right kind of tennis shoes. Oh well. Let’s get this over with.

Here they come in their team van. Oh God…look at their uniforms. How embarrassing! They’re not even all the same shade of white. Some look yellowed. Some girls aren’t wearing the right kind of tennis shoes. Oh well. Let’s get this over with.

As we began playing, I remember feeling the courts were very private and special. Carl Hayden’s were situated right by 35th Avenue so there was lots of noise and no privacy. The Camelback girls seemed a little precocious the way they talked to one another, saying things like “a little help please” when the tennis balls from one court ended up on another. I was used to saying things like “Marci! Get the ball!” There were large coolers filled with cold, icey water and Gatorade. At Carl Hayden, we only provided fountain water, no ice, no cups. I felt very confused.

The

girl I’m supposed to play isn’t wearing as much makeup as the other

girls. Her name is something like “Weeona” or “Ramona”, not the

usual Veronica, Monica, Jessica. She thinks she’s a professional

because she’s not using the school issued tennis racket—she has her own

Chris Everett racket. My teammate and I make eye contact and

start laughing. We’re probably both thinking the same thing—poor,

Mexican girls from the west side. They all look alike with their

dark hair and eyes. I would just die if I had to wear those

uniforms! It’s weird…I wonder why their coach works at that

school. She seems nice. She’s an older, white lady. I

wonder if she’s ever nervous going to work every day? It must be

strange knowing that all of your students are poor Mexicans and

probably don’t even want to be there. Hmmm….listening to the girl

I’m playing calling out the score…she doesn’t really sound Mexican…

I felt what I can now identify as inferior from a very distinct difference in social class. My friends and the students at Carl Hayden and my neighborhood all had a sense of “togetherness”, like a big family. In spite of our differences, I think we were bonded by the very nature of where we lived and went to school. Yet, on the Camelback courts, I suddenly felt underprivileged and “less than”. The contrast in social class was obvious, confusing and almost depressing.

To this day I remember the impact this episode had on me. I felt judged not only for what I was (from a poor school), but for what I wasn’t (not upper crust enough) AND for what I was perceived to be (Hispanic). There was a definite difference in our economic classes, probably the quality of our education and even in our tennis skills (a lot of the Camelback girls had private lessons!) But I really FELT these differences, and it felt shaming. It is interesting to reflect on it today, that although there wasn’t anything tangible going on that one could prove, the prejudice and stereotyping was obvious. How enlightening to have been subjected to prejudices of class and ethnicity as a young, white female by other young, white females. The situation truly allowed me the opportunity to experience something as an ethnographer and as the “Other”.

I believe that this “incident” stuck with me not only because of who I was at the time, but who I still consider myself to be. Often, I was labeled a “Pollyanna”, someone who was overly optimistic. It was difficult for me to believe that there could be conscious evil, especially surrounding race, ethnicity or class. I think that’s why when I experienced it first hand I was so disillusioned, so affected. I believe that we all have something to offer. Sometimes it’s difficult to see what it is another has to offer, but it’s there--even if only to enlighten our own selves about something. This “opportunity” allowed me to experience a certain prejudice, stereotyping, or labeling that I might not have realized could happen. Knowing in my heart that I had done nothing more to deserve it than exist was convincing enough for me that inequalities do exist, in spite of my optimism.

When I grew up, I married a young white man who had many future goals in mind. He seemed structured, goal-oriented and stable. This ultimately resulted in perfectionism, criticism and little acceptance for who I was. He eventually started abusing me emotionally, verbally and finally physically. After 18 months, we divorced.

I eventually married someone I had known from high school. A Hispanic; someone who knew the reality and unfairness of diversity. We embraced one another for who we are, and did not criticize one another for who or what we aren’t. We have two beautiful children who embrace diversity, who are not afraid of difference, and least of all, criticize it. I remember my daughter in first grade describing an African American girl as “…so pretty, Mommy. She has the darkest, prettiest skin I’ve ever seen.”

I like to think that being “white” and “middle class” attending a “poor, inner-city, minority” school taught me life lessons I may never have identified. Text book knowledge and logical awareness is not nearly as effective as a real life experience.