FIFTH LECTURE

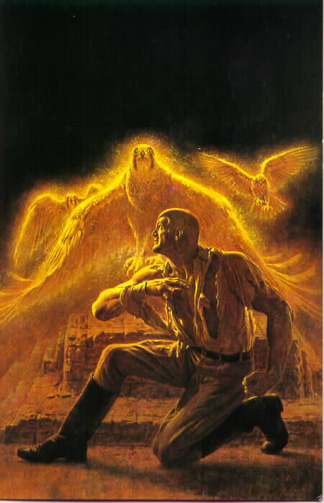

The Flaming Falcons - by James Bama

A profound shift begins to occur in science fiction by the early Sixties. Without going into too much historical detail---most of which you probably already know---America was in the process of becoming entangled in the civil war in Vietnam. We had begun sending "advisors" (a euphemism for the Green Berets) to assist the government of South Vietnam in 1958 after France had long abandoned its colony there and by 1963, when Lyndon Johnson became president in the wake of John F. Kennedy's assassination, we were up to our knees in the war and all manner of domestic unrest at home. The Civil Rights movement was in full swing and the environmental movement saw its beginnings during this period as well (mostly because of what napalm and Agent Orange did to the people who both dumped it and the people upon whom it was dumped).

Meanwhile in the Soviet Union Brezhnev was in, Khrushchev was out. Cosmonauts and astronauts were setting their sights on the moon. The times were a changin', to quote Bob Dylan, and life at home and abroad was becoming a bit surreal. Science fiction, however, was a few steps ahead of the game.

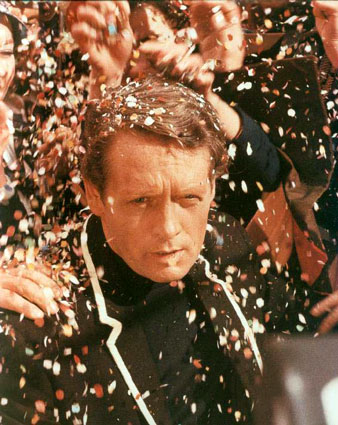

Indeed, one of the most important science fiction television series of the decade was the very surreal show, The Prisoner, which starred Patrick McGoohan. The Prisoner single-handedly put an end to the romance of the spy thriller. I Spy, The Man from U.N.C.L.E., Our Man Flint, even Get Smart were all dealt a mortal blow by what The Prisoner really suggested about Cold War politics as well as the power of governments to manipulate individual lives for its own purposes.

The "real" Village is actually a holiday resort in Portmeirion, Wales.

In The Prisoner a secret agent, and presumably a British citizen, is kidnapped by an unknown agency and kept at a place called "The Village," isolated away from the rest of the world. The keepers of the Village are never identified; they could be British or Soviet or rogue agents. And little else is known about Prisoner himself. Was he merely quitting the British Secret Service because he was tired of his job or was he in fact about to defect? The Prisoner is very Kafkaesque in its themes and it became a stunning metaphor for the ultimate corruption of government agencies by the end of the 1960s.

The fact is that people power--and America is not immune here--have always abused power whether it was given to them by the people or whether they took it for themselves. So it always was, so shall it always be. Science fiction allows us not only to speculate, but it also allows us--and sometimes compels us--consciously or unconsciously to express our fears and dreads in a fictive setting. Stories about Mars or the far future, or stories about about alien invasions, are usually just metaphors for life as it is lived (or as it perceived) in the present day. But even going back to Heinlein's time, writers of science fiction always dreaded the overreach (or its possibilities) in the government. When Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, the Warren Commission was painfully (and forensically) lacking in the kinds of details that would convince even the most casual reader that one person had acted alone. Then the uncontrollable Vietnam War was followed by Watergate, and soon an entire generation distrusted what "Big Brother" was telling us. He was saying: "Ignore the man behind the curtain!"

We would not.

This meant that life in America was becoming scarier. Writers such as Ray Bradbury, Robert Bloch, and Richard Matthiesen could tap into these primal fears of the Fifties and Sixties and create some of the most classic stories in the science fiction field.

Ray Bradbury, a writer John Campbell would never have published, became one of the greatest SF writers of all time by going soft on the "hard" sciences and mixing in a little horror and a little fantasy in his stories. Unlike the writers of Campbell's stable, Bradbury wrote in a highly metaphorical style, rich in both Gothic elements and symbolism-something John Campbell and the die-hard readers of Astounding wouldn't have had the patience for. Bradbury, the Kuttners, Sturgeon, Blish, and Heinlein were the giants of the transition in science fiction from the late 1940s into and through to the end of the 1950s. While Astounding plodded along with its same, narrow vision, many of Astounding's former writers found Campbell's influence a bit stifling. Heinlein left, so too did Theodore Sturgeon. Science fiction was changing, developing a more human, social side, sometimes analyzing the inner life of human beings in the future as well as their outer lives.

Bradbury's stories often involved ordinary people, people usually from the upper Midwest, where Bradbury grew up, who found themselves in extraordinary situations. And usually, tragically, there was very little they could do--because they were usually ill-equipped to do anything. This has much to do with the paranoia of the "little guy" during the cold war (witness the Bixby story) where immense forces were at work and there was nothing anyone anywhere could do about it. Thus, the small-town "episode" that unfolds in "Mars is Heaven!" remains one of the best Cold War horror stories yet written. It suggests life isn't innocent and terror and horror lurk right around the corner.

Bradbury's stories from the very beginning were powerful and poignant and remain so to this very day. In fact, of the 300 or so stories Bradbury has written, few were originally published in science fiction magazines. Bradbury was one of the first SF writers to crack the "slicks" and reach a wider audience. He was a favorite of magazines such as Collier's, Saturday Evening Post, and later on, Playboy. His stories have been transcribed into episodes of many early television series, notably The Twilight Zone and Alfred Hitchcock Presents, not to mention the movies made from his books: Fahrenheit 451, The Martian Chronicles, Something Wicked This Way Comes, and The Illustrated Man.

At this time in the early 1960s science fiction was beginning to prosper, mostly because publishers began to see science fiction as a viable publishing endeavor and publishing houses which previously did not have a science fiction line began creating them. Or put differently: there was a lot of money out there to be made because there was a hungry audience ready to read just about anything that looked good. Thus, by the 1970s, science fiction books would begin to appear on The New York Times Bestseller's List.

More writers than ever were entering the field, and few, if any, were strictly in the Campellian camp. Moreover, fantasy began its rise at this time, simply because the market had opened up once the reading public discovered the novels of J. R. R. Tolkein. This leads us to a very important (though often ignored) publishing phenomenon that came about in the early Sixties. This was the rediscovery---and in many cases, the rehabilitation---of the great pulp heroes of the 1930s. And we start with Edgar Rice Burroughs.

|

|

|

Frank Frazetta's covers for Ace Science Fiction in their Edgar Rice Burroughs reprints.

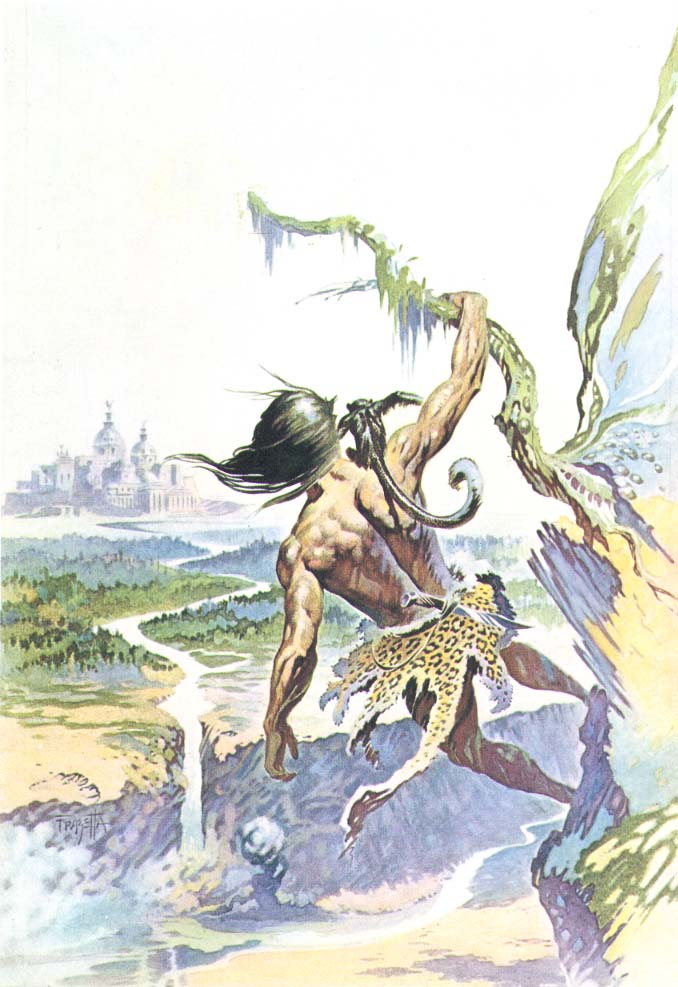

In the early Sixties, Ace Books began reissuing the pulp adventure novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs. Burroughs had always had a following mostly because of Tarzan. Yet his science fiction adventures were less well known to younger readers (the person writing these words, for example). Previously, the tales of John Carter and those of Carson on Venus, to say nothing of the Moon Maid and all those people who lived in Pellucidar, only existed in expensive hardbound editions available only in ibraries. A wider (and younger) market had yet to be tapped.

Ace Books obtained the rights to all of Burroughs' novels and reissued them all in about a four-year period. More importantly, Ace published them with brilliantly evocative covers by Frank Frazetta. As such, Ace almost single-handedly created the market for fantasy in one bold stroke. Ace Books had originally entered the paperback market in 1953, publishing mostly westerns in a "double" format: two novels (actually novellas) back to back, with one novel upside down to the other. Ace also published science fiction in the "double novel" format.

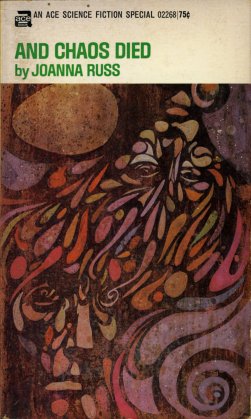

Two of the forty or so Ace Science Fiction Specials.

However, in the 1960s, Ace became a major publisher of science fiction with their crowning achievement being the Ace Science Fiction Specials, of the late 1960s and early 1970s, that were edited by Terry Carr with extraordinary covers by Leo and Diane Dillon. Some of the most important novels in the science fiction field appeared as Ace Science Fiction Specials--Ursula K. LeGuin's The Left Hand of Darkness, John Brunner's The Jagged Orbit, Philip K. Dick's The Preserving Machine and Roger Zelazny's Isle of the Dead.

And let's not forget Conan the Barbarian. Conan was the brainchild of Robert E. Howard, friend and soul-mate of H.P. Lovecraft. Howard, a prolific pulp writer from Texas, published most of his stories during the 1920s and were a staple of Weird Tales magazine. He committed suicide in 1936 and never witnessed the impact his fiction (or his famous barbarian) had on the field.

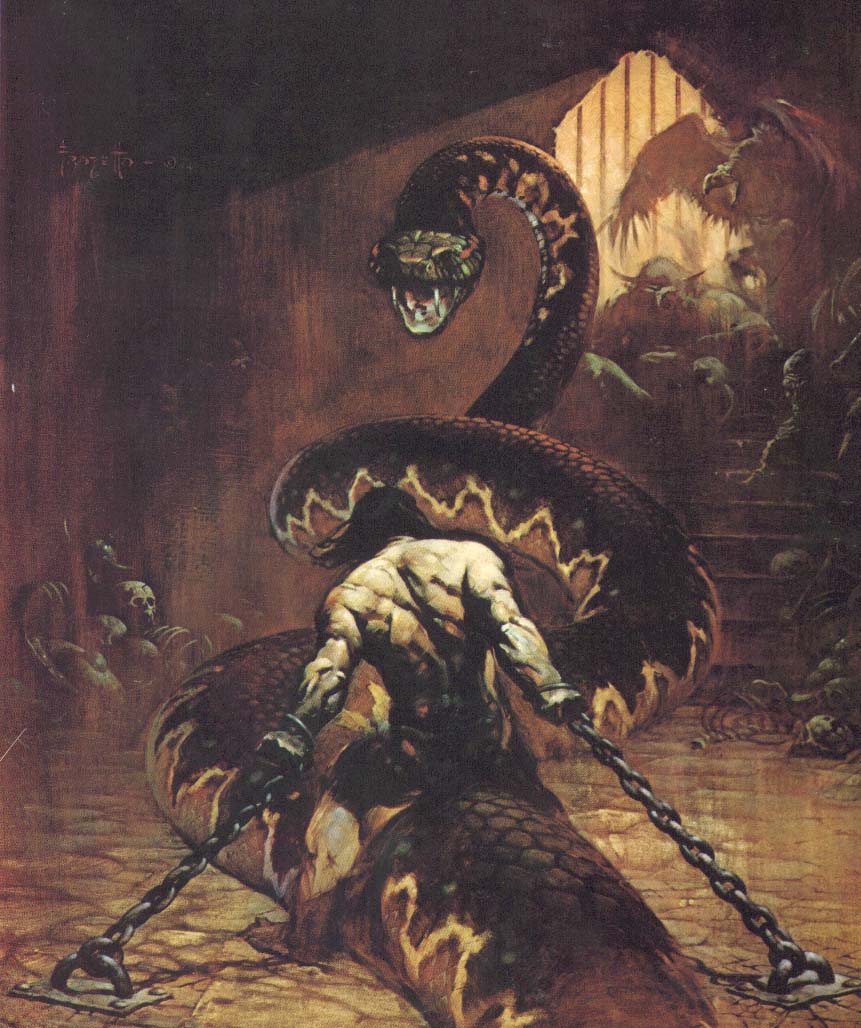

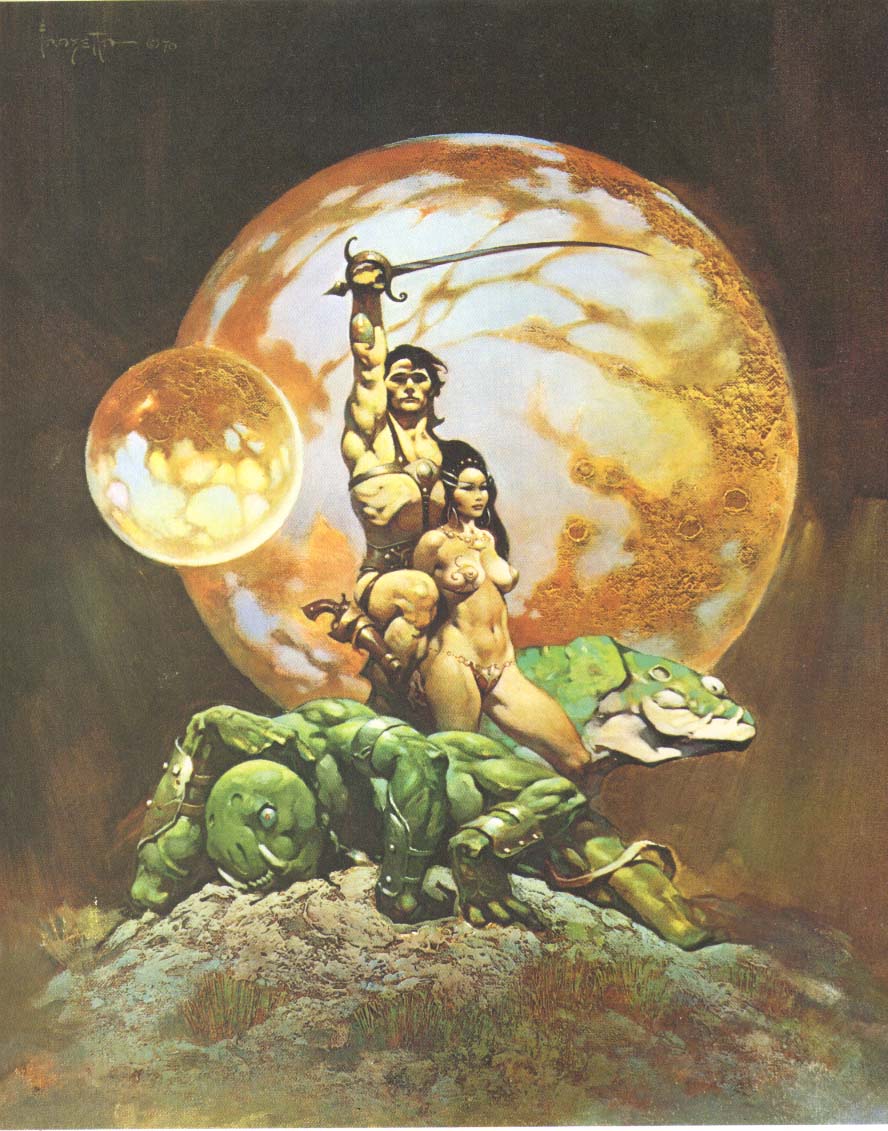

Frank Frazetta's stunning cover to the Lancer Books 1967 reprint of Conan the Usurper.

Though Howard's writings experienced a brief revival in the early 1950s, Howard was really put on the map when Lancer Books, a small New York paperback company (now deceased) published nearly all of Howard's Conan stories, edited by Lester Del Rey and Lin Carter. Lancer Books also employed by Frank Frazetta to illustrate the Conan covers. Frazetta's art appeared on a number of fantasy adventure books in the 1960s, but in 1964 the pulp revival really took off when Doc Savage, the greatest pulp hero of them all, came back to life.

Image of the original Doc Savage, Jr. by Walter M. Baumhofer,1934.

In 1964 Bantam Books decided to resurrect Doc Savage in a numbered series format of paperback books. At first they had only intended to publish eight stories, but when the series unexpectedly took off, Bantam committed itself to publish all 187 novels that had been originally published from March of 1933 to November of 1949. No publisher had attempted a numbered series before, so it was very much a publishing risk on Bantam's behalf. The generation that had read Doc Savage Magazine in the 1930s was very much alive, but the real money lay in getting newer readers who were born after the era of the pulps (your instructor). Bantam did this the same way that Ace and Lancer Books did with their Burroughs and Conan series. They "jazzed up" the image of their character for a younger, television-oriented age and soon every pulp hero found a new publisher in New York. Doc Savage was the most successful of them.

Bantam, however, wanted a more updated, "modern" Doc Savage and employed commercial artist James Bama to give Doc Savage a makeover. Bama's Doc Savage was a golden-skinned, blond-haired physical superman with a pronounced widow's peak. With riveting golden eyes and torn shirt, this Doc Savage meant business. And off the series went, exposing a whole new generation to the fantastic literature of the 1930s (to say nothing of some pretty spectacular writing, especially in The Lost Oasis and The Thousand-Headed Man).

Detail from James Bama's The Thousand-Headed Man

The influence of the Doc Savage stories and the central character cannot be measured, but many movies have been made using the Doc Savage archetype including The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai and Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Others have seen the archetype (a charismatic leader and a team of specialists) in Arnold Schwarzenegger's Predator and the most recent League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow. It's an archetype that is particularly American and comes out of a typcially American "can do" attitude that really came of age in World War Two when anyone who could, did--because they had to. There were real enemies abroad at that time.

But if the Doc Savage stories seemed a little dated as the Sixties wore on, it was only because the world was changing at a horrendous rate. Everything seemed to change at once, both at home and abroad. Music, movies, fashion, even morals felt the hammer-blows of change, even at times leading that change. And science fiction was as much a part of it as anything else.

But the stigma of being a genre known for its bad writing began to lift in the 1960s when the entire field fell under the influence of editors such as Michael Moorcock, Terry Carr and, later on, Harlan Ellison, who encouraged their writers to write at the absolute peak of their ability. As such, the first genuinely difficult science fiction begins to appear at this time. John Brunner's Stand on Zanzibar (1969) and Ursula K. LeGuin's The Left Hand of Darkness (1970) won Hugos for the best novel of their respective years, yet both pose unfamiliar rigors for the average reader.

|

|

These are not "pulp" adventure stories and tended, as is the case with Le Guin, to resemble philosophical novels such as those of Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus (and Philip K. Dick would come closest to resembling Gogol or Kafka).

But these novels could never have been published a mere decade earlier. By the early 1960s, though, the audience for these books was in place. This audience was now in college, musically hip, and politically savvy. And not a small part of that audience was dabbling in the drug culture of the time, experimenting with the frameworks of consciousness, looking to see if there were other ways of characterizing human experience. Science fiction was no less affected. This was a culture-wide change and a great deal of mainstream literature had undergone the same changes.

In the real world, grownups such as Thomas Pynchon, Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Carlos Castaneda, Robert Coover, Paul Bowles and William S. Burroughs (no relation to Edgar Rice Burroughs) were burning up college English classes with their wit, wisdom, and surreal visions of realms hitherto unimagined. Overseas Italo Calvino was writing his fantastic fictions; in South America, Jorge Luis Borges and Gabriel Garcia Marquez were inventing magical realism all on their own.

And how did this sea-change come about? One reason for this was that right after World War II, everyone started going to college. College, something heretofore inaccessible by any but members of the upper classes, became a middle-class goal. Much of this came about because of the various veterans benefits enacted by Congress in 1946 and 1947 to get veterans into college so they would have usable skills on returning to society. In simple fact, the American reading public became smarter and it showed in the level of sophistication in poetry, fiction, drama and cinema, not only in America, but in Europe as well.

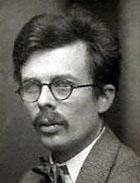

The other factor at this time that became a major influence in the culture of the era was drugs. Just about everything in popular culture became influenced by people (writers and civilians alike) using marijuana, LSD, and other drugs. Many literary figures dabbled in the use of drugs, not the least of which was British writer and philosopher Aldous Huxley who saw psychotropic drugs as a means to gain access to a higher reality. Huxley, the author of Brave New World, also wrote a seminal work on mescaline and peyote called The Doors of Perception.

Aldous Huxley

Quite a lot changed because of hallucinogens. Everyone from the Beatles on down (or up) seemed to be doing them. Even cinema directors experimented in strange modes of filming, sometimes inventing modes of storytelling that moved beyond the logical and the linear (this would lead to movies of the 1990s such as Pulp Fiction that tells its story in a fractured manner) . During the 1960s the films of Fellini, Kurosawa and Bergman were changing the way directors told their stories. This happened in science fiction as well.

This isn't to say that the science fiction field became flooded with drugged-out literary experiments such as Brian Aldiss' aforementioned Barefoot in the Head (1969) and Thomas Disch's tour de force also of 1969, Camp Concentration. But we must remember that writers are also part of the culture and their points of view often show up in their fiction. Some did drugs; most didn't. Few who did drugs found that it affected their writing. Others were quite impressed by the experience. (We'll alk about Philip K. Dick in a minute.) But the writing in the field did change during this time and many brave editors advocated such writing. It certainly found a place in the hearts and minds of readers.

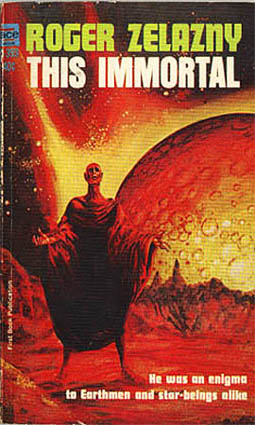

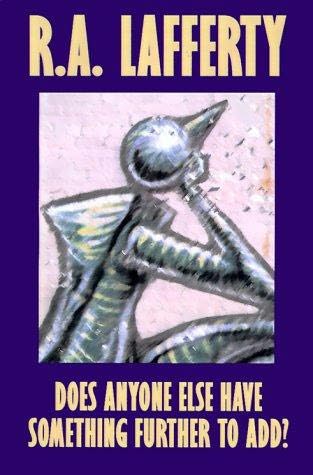

Still, many writers emerged whose simplicity of writing style and sheer sanity seemed to be at the opposite end of the stylistic spectrum. Writers such as Samuel R. Delany, Jr., Roger Zelazny and R.A. Lafferty are almost the complete opposites of Aldiss, Disch and LeGuin. These writers managed to emphasize the simple art of storytelling without letting the words get in the way.

|

Roger Zelazny |

|

oger Zelazny has an amazingly unadorned writing style; yet his stories zip right along with both humor and poignancy. "The Great Slow Kings," a terribly funny story all on its own, gains its impact from what we all know of human folly. Like a lot of SF that appeared after Astounding, "The Great Slow Kings" suggests that humans might not be able to "make it" as a galactic species, something John W. Campbell, Jr. would never have advocated. Zelazny, like Ray Bradbury before him, wrote a number of stories that were, at their very center, tragic. His stylistic simplicity belies the heart of a great moralist.

R.A. Lafferty is another kettle of fish entirely. Lafferty's forte was the short story and what short stories they were! Part fantasy, part SF, and part magical realism, afferty's stories inhabit a realm of their own. Few of his stories were ever meant to be taken literally, yet they all resonate with deeply conjured truths.

|

|

A Slow Tuesday Night" is probably his most anthologized short story and its endurance in the canon lies in its clear metaphorical applications to what life in America has become today. Rock groups become instant millionaires practically overnight (they're called One Hit Wonders) then fade away, never to be seen or heard from again. Fads in clothing-or anything else for that matter-appear and disappear in the blink of an eye. (Like, whatever happened to Hootie and the Blowfish and Soundgarden and Alice in Chains and Stone Temple Pilots?) This wonderful short story has all the satiric ring of Vonnegut's "Harrison Bergeron" which describes yet again another aspect of the American culture. (I would equate in spirit many of R.A. Lafferty's short stories with those of magical realist Jorge Luis Borges. They are that good. Lafferty, however, has more humor than does Borges.)

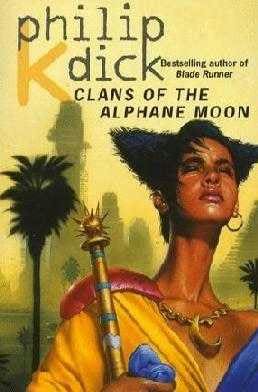

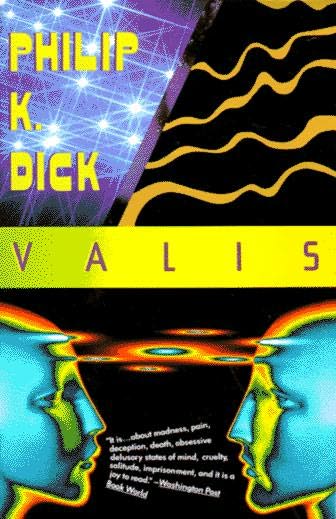

Our final two figures have had an ongoing and lasting effect on the science field and they have helped in convincing the world that science fiction is actually literature and not the juvenilia that academe has traditionally claimed it to be. These writers are Philip K. Dick and Harlan Ellison. Philip K. Dick's writing career started in the early 1950s when he attempted to become a mainstream writer. When that failed, his friend Donald Wollheim suggested that Dick turn his sights to science fiction. Dick became an immediate hit with readers and produced an extraordinary body of work in both short fiction and the novel. His fiction has been called paranoiac, visionary, transcendent, and just plain crazy. All of those certainly apply.

Dick's novels and stories are virtually indescribable and they usually involve some sort of reality-bending crisis in the life of an ordinary individual (as in the recent movie Minority Report). Dick's writing is meticulously crafted, but his plots are absolutely unpredictable (rare for a field of almost formulaic plotting conventions). And sometimes the good guy doesn't always triumph in the end. In fact, there are times when nobody wins. Still for all that, Dick became one of the most respected writers the genre ever produced.

The story I've chosen, "We Can Remember It For You Wholesale" (which was made into the movie Total Recall), takes an ordinary man and thrusts him into a world he can't control. In fact, that world (an implanted vacation scenario) turns around andbites him in the ass-him and everyone else nearby. This is a wonderful Frankenstein story that takes several digs at science and technology, with not a few digs at American commercialism.

Another Frankenstein story is Harlan Ellison's brutal "I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream".Ellison's career began in the 1950s and he has created an enormous body of work, mostly in the format of the short story and novelette. But his has written several million words in articles, newspaper columns, screenplays, and teleplays. There is no kind of writing Ellison has not touched upon (except maybe cookbooks, but I could be wrong in this). He has even scripted a number of issues of a wide array of comic books. Ellison's stories tend to be satires or monstrous visions of the future, and they are all written in one of the most characteristic writing styles in the field. His stories grab you by the short hairs and takes you where you don't want to go, but go there you do.

As you've seen, the late 1960s in both America and Britain was a time of great experimentation in all of the arts. Movies changed, music changed, the world was rocking and rolling to the beat of Huey helicopters prowling the skies above the rice paddies of Vietnam. In England, New Worlds was giving Brian Aldiss, John Brunner and J.G. Ballard a chance at spreading their literary wings. All of which led to the creation of a literary phenomenon called the "New Wave."

This is a book you must have.

But back in America, Harlan Ellison's contribution to the New Wave was a book he edited called Dangerous Visions. Ellison convinced Larry Ashmead at Doubleday to do something that had never been done in publishing before. He convinced Doubleday to publish a massive book of original science fiction-not a reprint anthology- but it would be a book of science fiction stories so radical that they never would be accepted by the normal SF magazine outlets. This book, when it came out, rocked the science fiction (and publishing) world. Among its 33 extraordinary stories were the award-winning "Aye, And Gomorrah ..." by Samuel R. Delany, "Gonna Roll the Bones" by Fritz Leiber and "Riders of the Purple Wage" by Philip Jose Farmer. Indeed, Dangerous Visions might be Ellison's lasting achievement. Not even his own radical fiction has had the impact that Dangerous Visions has.

Whether science fiction needed a shot in the arm in 1967 is a matter of debate because fine science fiction was already being produced by dozens of wonderful writers. It was also evident that by 1967, the "hard science" story advocated by John W. Campbell Jr. was no longer the only kind of story writers wanted to write and readers wanted to read. Science fiction had expanded right along with the general culture even if the influence of John Campbell still resonated throughout the field. Remember that Star Trek, the television show, ran from 1966 to 1969 and it was based on A.E. Van Vogt's Voyage of the Space Beagle, itself a product of Astounding Science Fiction. In fact, science fiction remained conservative in cinema until the 1980s when Blade Runner, directed with great stylistic flair by Ridley Scott, came along. Indeed, science fiction cinema today seems to be advancing by greater leaps and bounds than the written word, perhaps due to the advances in special effects technology and CGI software. Steven Spielberg's Minority Report is a grand stylistic romp as is Terry Gilliam's 12 Monkeys, and The Fifth Element is just plain fun to watch.

As it is, science fiction will undergo a few more changes in the Contemporary Era (1967 to the present), but if you've tracked these lectures all the way to this point, you should have a solid foundation of the origins of science fiction and how it came to be what it is.

I have one final comment. You will have noticed that I have virtually (though not entirely) ignored women---or more properly speaking, women writers---in this course. I wasn't quite "ignoring" them. Until the late 1960s, after the period covered in this course, women authors had not entered the field in any huge numbers or written stories as powerfully significant as the men in the field up to that time. Then again, for years it was mostly an adolescent male's domain. Even movie serials of the 1930s and 1940s were mostly aimed at boys (and white, male boys, at that). Not so anymore.

As always in our culture, it takes a while for minorities and women to catch up to most things. So, too, science fiction. But they are with us now. With Judith Merril and Catherine L. Moore already mentioned in this course, we have Ursula K. LeGuin, James Triptree, Jr. (the pen-name of the incredible Alice Sheldon), Kate Wilhelm, Andre Norton (Alice North), Katherine MacLean, Anne McCaffery, Zenna Henderson, Octavia Butler, Pat Murphy, Patricia Anthony, Pat Cadigan, Connie Willis, Pamela Sargent, Linda Nagata, Sherri S. Tepper and dozens more.

Quite a few women were writing in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and one of the ones who made the transition into feminism was Joanna Russ. The Modern Feminist Movement began when Betty Friedan published her 1963 book The Feminine Mystique. Modern Feminism is an outgrowth of the civil unrest of the 1960s and the Civil Rights Movement. As some groups began to fracture on the political Left, one group that came together was centered around the rights of women. There is no hard line of demarkation that suggests that feminism began at a certain date, but by the early 1970s, women were beginning to make greater inroads in the academic world and especially that of publishing. Female science fiction writers had always been around, of course, but not so nearly appreciated until female scholars, critics, writers, and editors (Judith Merril and Judy Lynn Del Rey) came along. Joanna Russ's story "When It Changed" is no less brutal that the Ellison story and no less visionary. It was one of the first stories that brought into greater perspective issues of gender, gender relations, and what human beings in general sometimes have to become in order to survive.

Joanna Russ |

Though we are at the end of the class, I do recommend that you track down the works of the other great female science fiction writers, especially the novels of Ursula K. LeGuin, the short stories of James Triptree, Jr. and when you have nothing else to do with your life, read Sherri S. Tepper's novel, Grass; then run out and buy Pamela Sargent's novel, The Shore of Women.