FOURTH LECTURE

The stories in this section were written from the mid-1950s to the early 1960s, a period of time that saw the end of the somnolent Eisenhower administration giving way the promise of John Kennedy's administration. What we got was a decade of extraordinary change. The threat of the Cold War and nuclear annihilation now seemed quite likely, with the actions of Soviet Russia during the short-lived Hungarian Revolution in 1956 further convincing everyone that the Soviets meant business and were quite possibly as evil and tempestuous as they seemed to be. Certainly the Hungarians had reason to think so.

Thank you very much.

At home, so did Joseph McCarthy, who saw communists everywhere and persecuted them in Congress, doing more for the "Red Menace" than the Red Menace could do on its own. By 1955 the world seemed clearly polarized into two distinct political entities (us and them) and fifth columnists were everywhere undermining society. Just ask J. Edgar Hoover. He had files galore on every major writer in the country who had any leanings toward the left. His favorites were Sinclair Lewis and John Steinbeck. Later on, he took an interest in John Lennon, The Doors, Andy Warhol and women's apparel.

One overlooked development during 1950s was the transformation of rural China into a modern communist state. Mao Tse-Tung, gifted poet and rural revolutionary, brought China into the 20th century by wresting it away from the clutches of a weak oligarchy helmed by Sun Yat Sen who, in turn, wrested it away from an effete royal line that had nothing but their own interests in mind. But almost as soon as Mao Tse-Tung grabbed hold of the government, China went absolutely quiet for a couple of decades. China would suddenly reappear on the world's radar screen when they obtained nuclear weapons technology and aggressively backed North Vietnam in their civil war with the South. Geopolitics was beginning to rear its ugly head and the comforting isolationism of the 1950s was about to end.

Also at this time, China was also at loggerheads with the Khrushchev in the U.S.S.R. because Khrushchev was a rabid anti-Nationalist, which meant that he didn't like Soviet satellite countries, China included, to retain any semblance of national or ethnic identity. The Hungarians experienced this doctrine 1956, so too the Czechs during the Prague Spring which lasted from January to August in 1968. But when China developed (stole) plans for the hydrogen bomb, the world became a much more dangerous place. Both the Americans and the Soviets began to sweat a little bit more because each had two adversaries, not one.

Soviet Tupolev "Bear" Bombers often skirted the American coast during the Cold War to test our defenses and reaction time. Here, one is being escorted into safer territory by an F-14 Tomcat. This kind of behavior goes on all the time all over the world. This is what's often called "brinksmanship."

The movie, On the Beach, was an international hit during this time. It was also "banned in Boston" by the Roman Catholic diocese of Massachusetts, mostly because the way the novel and the movie ends: Everyone dies. Everyone. Its bleakness was so horrifying that there were protests in many capitals of the world when the movie came out in 1959. (Critics will later respond that, while the movie was a good polemic, it didn't really show what a slow, horrible -- and painful -- death from radiation poisoning would be like. Either way, it's pretty grizzly.)

Other novels of the time, George Stewart's Earth Abides and Pat Frank's Alas, Babylon also echo the same Cold War fears. Here, it's not scientists who are out of control; it's the technocrats, those who use science (and its weaponry) to enforce public policy. When this happens, it usually has disasterous consequences.

In the 1980s, Jonathan Schell's The Fate of the Earth, a stark analysis of the real effects of a nuclear war, would evoke a similar response, suggesting that even a minor nuclear strike on any major city in the world would be catastrophic. Its results would be felt across the entire ecosphere. All of this, of course, was fictionalized in Nevil Shute's On The Beach.

|

|

Nevil Shute

Science fiction had, of course, been at the forefront of the dangers of nuclear radiation since Marie Curie and her husband died of radiation poisoning in 1934. She may have discovered radium, but in the end it killed her.

Then Lester Del Rey made a name for himself with the field's first story of a nuclear accident in "Nerves" in 1942 and the Fifties were full of stories involving all kinds of mutants from the giant ants in "Them" (1954) to the X-Men movies of recent vintage. What's at work here is the Frankenstein monster of the nuclear genie: once it's let out of its bottle, there's no telling what sort of damage it can do. So during the 1950s it was much easier to simply ignore the monster rather than face it.

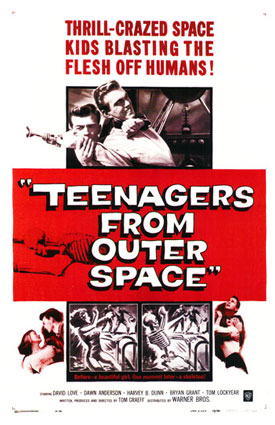

Of course, monsters were with us in the Fifties . . . as was the ubiquitous drive-in theatre (a dying breed these days). The new American suburbanites with their new American convertible cars spent their weekends at the drive in theater where you could see all manner of movie mutants.

|

|

|

|---|

And, of course, Godzilla.

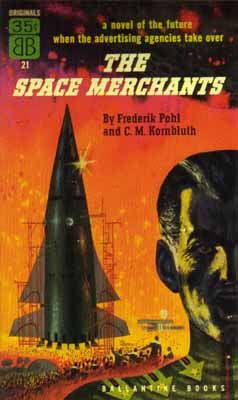

America, however, snoozed straight through most of the 1950s, and most of it, if not at the drive-in, then in front of a television set. Television and the development of the suburbs seemed to be the promise of the American dream, at least for the greater (and mostly white) middle class. Science fiction, however, often reflected this growing complacency of the (once again white) middle class, as did mainstream literature of the time. These are the great years for mainstream fiction about the new middle class published in The New Yorker. The stories of John O'Hara, John Cheever, Saul Bellow, and John Updike poignantly chronicled the plight of the middle class during this decade. Science fiction, meanwhile, often found themselves making fun of it. One of the best satires of the Madison Avenue cult of advertising is The Space Merchants by Frederick Pohl and C.M. Kornbluth.

Science fiction writers themselves were not immune to the changes America was feeling in the post-WW II years. The field begins to see science fiction taking on the role of social criticism, suggesting that perhaps our whole society has become something of its own Frankenstein monster. Certainly the ongoing nuclear testing program by the superpowers didn't do much to calm the nerves of the American public, with Great Britain and France soon to develop their own nuclear weapons. Something seemed to have gotten out of whack and everyone alive during the late 1950s felt it. Add to this the development of the intercontinental ballistic missile and field nuclear weapons and everything starts to get really scary. (And now, as late as January 2006, Iran is making nuclear noises, again. It never seems to stop, does it?)

Illustration by James Gurney.

It's one of the great ironies of predictive science fiction that no one saw that governments, not corporations or maverick individuals, would be the first in space and to be the first to set foot on the moon. Science fiction, of course, had been in space for over a hundred years in projectiles of one kind or another. But nearly all science fiction stories had men and women traveling to the stars under the auspices of corporations out to do business or individuals plying their own trade and playing by their own rules. Here think of Han Solo and The Millennium Falcon. In fact, this particular conceit is still being practiced today. The best current writer in this vein is C. J. Cherryh. Her novel Downbelow Station chronicles a wide group of corporations trying to get economic control of a planet (and the general space around it) with all sorts of complicated results. Indeed, in this day and age, one often finds corporations trying to rule the world rather than individual crazy people or entire governments. The RoboCop movies come to mind in this regard.

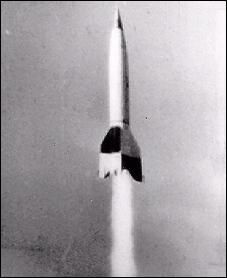

In the mind of the public, however, the space race made space travel palpably real. The public already knew about V-1 and V-2 rockets that Germany had developed during the Second World War. Everybody knew that both America and the Soviet Union were testing rockets that might someday launch a man to the moon. And, of course, the entire culture had almost a century of science fiction (good and bad) in the movies telling us where we were headed and what kinds of machines were going to get us there.

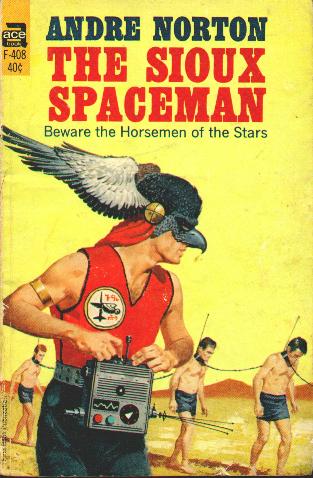

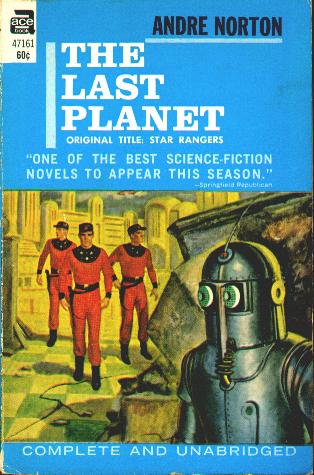

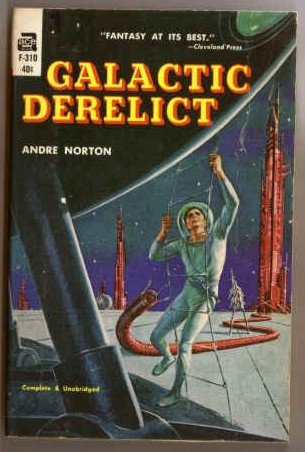

During the 1950s, television shows such as Tom Corbett and the Space Patrol, Men in Space and The Adventures of Colonel Bleep captured the imaginations of youngsters much the same way that the Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon serials captured the imaginations of kids during the 1930s. In this way, as some critics have pointed out, the genre of science fiction has a built-it growth factor. No other genre begins with readers in their early adolescence and keeps them into adulthood. Most readers come to the other genres as adults. Still, some of the best science fiction of this period came from the pen of Alice North writing as Andre Norton.

|

|

|

|---|

Ace Science Fiction was one of the leading publishers in both science fiction and fantasy. Mostly edited by Donald A. Wollheim (who later on founded DAW Books), Ace books also featured the first - and often only - editions of Philip K. Dick's novels.

Though her books weren't marketed specifically to younger readers, many who came to science fiction in this period did so through the paperback titles of Andre Norton. (This was also when Robert A. Heinlein was writing his "juveniles".)

Still, the space race was serious, with space itself an unforgiving environment. Missiles will blow up on launch pads. Satellites will fail to make orbit and burn up on reentry. Astronauts and cosmonauts will, in their turn, die. In 1970, Apollo 13 will nearly end in disaster and the space shuttle Challenger will blow up in January 1986. All this is to remind us that space travel still is a very dangerous undertaking. Science fiction writers have always known this and many still choose to write the occasional story with a realistic edge.

Tom Godwin's classic 1954 science fiction story "The Cold Equations" is the one story that truly represents Campbellian fiction at its rigorous best. You could also argue that it is not really a science fiction story. It's the one story in your anthology that comes closest to mainstream fiction because it adheres to science as we know it today: It's what would really happen if a ship had only so much fuel and so much time to reach a destination. No more, no less. The cold equations here are the simple mathematics of objects traveling in space. They have no regard for romantic adventures or heroism. They are indifferent to Hollywood conventions of shipboard romances and daring rescues. Godwin's universe is our universe and it's a very unforgiving one.

"The Cold Equations" might be unflinchingly brutal with its harsh realities, but contrast this with Alfred Bester's "Fondly Fahrenheit," published the same year as "The Cold Equations." "Fondly Fahrenheit" clearly is not a John Campbell story. It was originally published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Astounding's main competitor at the time. "Fondly Fahrenheit" is one of a legion of science fiction stories in the Fifties that explored the nature of consciousness, perception, and reality itself. This is also one of the first stories dealing with the interface between human minds and the minds of others-in this case a robot. The Cordwainer Smith story that follows "Fondly Fahrenheit" has humans interfacing with cats, of all things.

|

|

|

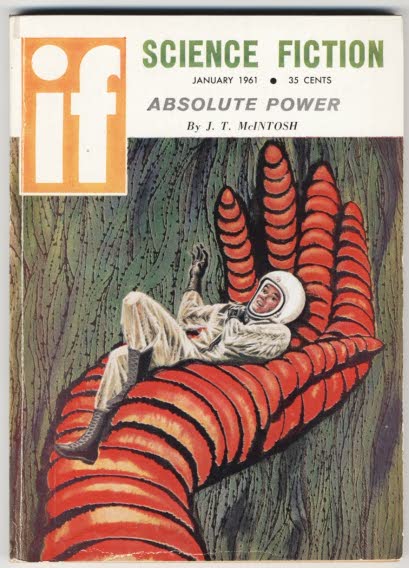

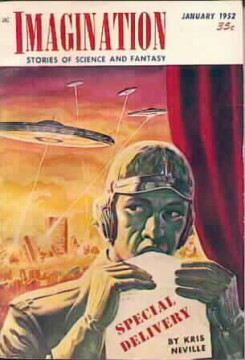

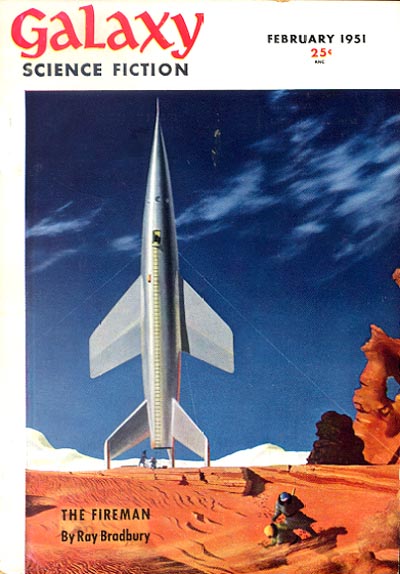

Galaxy, edited by H.L. Gold, emphasized the "soft" sciences such as psychology, sociology and anthropology.

In fact, during the mid-Fifties, most of the science fiction field had veered away from John Campbell's neat and tidy universe and explored, instead, the phenomenologically variable universes that human think they inhabit but in fact might not. Philip K. Dick began his extraordinary writing career during the mid-1950s and was on the forefront of stories that suggested that reality wasn't what we'd been told it was. We will end the course with a Philip K. Dick story that underscores this very notion.

However, these are stories that take the Frankenstein motif and turns it back on itself: The creator becomes (or becomes integrated with) the monster. Both "Fondly Fahrenheit" and "The Game of Rat and Dragon" approach this confused mind-body dualism with both humor and élan, but the field has just as many stories exploring the dark side of this interface. The movie The Matrix is a good example of this darker side. In The Matrix humans don't even know they're imprisoned in the brain of a giant, world-girdling computer. They don't know that, to the computer, they are nothing but batteries.

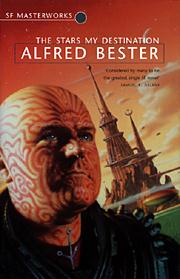

But while Cordwainer Smith (the pseudonym of Paul Linebarger) wrote stories of a fairly conservative nature, Alfred Bester is known for his literary experiments. Bester's best work is contained in two novels The Demolished Man (1953) and The Stars My Destination (1957). The Demolished Man is about a man who commits murder in a society filled with "Espers," police detectives who possess extraordinary powers of mental telepathy or extra sensory perception. (The Demolished Man has some similarities to the conceits of the movie, Minority Report. Both as the question: What would you do, if you were contemplating a criminal act, if you lived at a time when the police could anticipate your every move?) The Fifties were awash with stories of mental telepathy, a conceit that rarely occurs now (except when Obe Wan wants to get Luke to use the Force). However, Bester's The Stars My Destination uses odd typography and a mix of literary styles to tell the picaresque tale of Gully Foyle who learns a personal form of teleportation, "jaunting." Stories like this, stories that employ "fuzzy" science fictional concepts, were often rejected outright by John W. Campbell Jr. at Astounding (soon to become Analog in 1960).

Tales of ESP, however, took on their urgency at this time from everyone's fear of "Big Brother," the omnipresent father-figure ruling the world in George Orwell's novel 1984 (published in 1949) which was a bestseller during most of the early 1950s. Add to this the general fear in the population of communism, as well as Joe McCarthy's personal pogroms in Congress and you get a nervous public constantly looking over its shoulder for spies and God-knows-what-all lurking in every shadow.

Science fiction writers were often just ahead of the curve in capturing in print some of the terrors floating around in the back of our collective heads. And today, Stephen King is the best writer of stories involving ESP and telekinesis, most notably in Carrie, The Shining, The Dead Zone, Firestarter and The Green Mile.

Anyway, back to our stories.

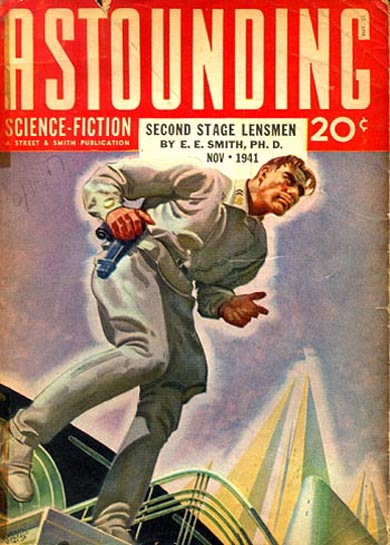

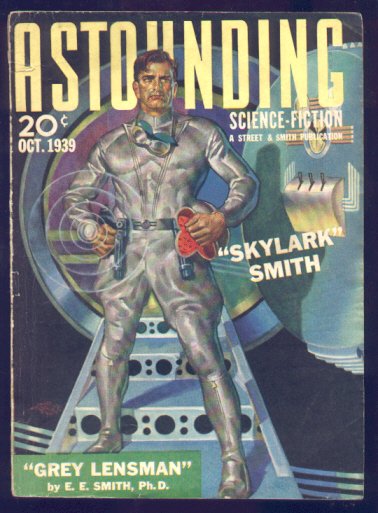

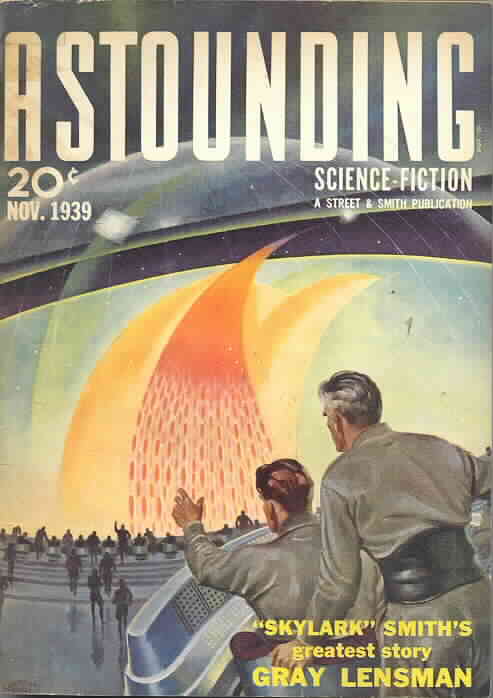

One of the most important science fiction writers to emerge in the 1950s was British writer James Blish. Blish was a thoroughgoing Campbellian most of his life and parts of his major work, his four-novel series called Cities in Flight, were published in Astounding/Analog. Cities in Flight still stands as a major achievement in the field, both as a concept and as a series. In these lectures I haven't really discussed the series either as a publishing phenomenon or as a science fiction and fantasy mainstay. There have been recurring characters in other genres of fiction (Zorro, Sherlock Holmes, Philip Marlowe, James Bond, etc.), but science fiction was the first field of literary endeavor to allow a longer story to evolve through separate novel-length narratives published over a period of years. E. E. "Doc" Smith's "Lensman Series" ranks as the greatest "Space Opera" and Isaac Asimov's "Foundation Trilogy" is known to one and all. Other great series are Frank Herbert's Dune series and Philip Jose Farmer's Riverworld saga.

|

|

|

|---|

E.E. "Doc" Smith was a mainstay of Astounding Science Fiction in the late 1930s through the 1940s. These novels contain the essence of "space opera" and everything George Lucas put in Star Wars (and more) can be found in the pages of these wonderful adventure stories.

James Blish's Cities in Flight, one of the greatest cycles in the history of science fiction, chronicles the development of "spindizzy" technology that allows whole cities to uproot themselves from the Earth and fly off into space to become cities of industry, looking for work. The story I've chosen in our anthology to represent James Blish is somewhat uncharacteristic of his writing, but its poignancy in nonetheless heartfelt. "A Work of Art" deals with the recreation of a "artist" in a culture that is only interested in entertainment and not so much the artist himself or aspects of his life. The irony here is that the "artist" in question actually has a depth to his consciousness and the audience and the creator miss it entirely. This is something of a sad Frankenstein story. (The story also bears some comparison to "Fessenden's Worlds" in that the creator doesn't fully understand his creation.)

"A Work of Art" also showcases another important aspect of science fiction. During the 1950s stories began to appear where the protagonist, normally a "common" individual, not a Campbellian hero, is in some way a reflection or product of his or her era and in some ways are stuck. These kind of stories, many of which are in your anthology, give us a picture of a character so enmeshed in his world that he can't see reality for what it is nor can he think of a way out of his problem. Note the characters in "Nightfall." Though they seem to grasp the problem, they nonetheless believe that there isn't anything they can do about the coming eclipse. They are products of an ingrained cultural passiveness which only makes their problem worse in the end. However, Asimov's stories more often than not involved scientists, not common people. But in the stories of James Blish characters often were helpless in the face of an oppressive culture around them.

Robert Sheckley shared some of this same perspective, only Sheckley was an out-and-out satirist. During the 1950s Sheckley became the embodiment of the Galaxy Science Fiction writer and wrote stories of sharp satire using all manner of science fiction tropes and conceits. "Pilgrimage to Earth" deals with another common theme in science fiction, the way in which science subverts and debases "love" (or any other human emotion), reducing it to its most marketable utility. The story is also (very cannily) about ideals and principles and the way in which these things get corrupted, even in the best of us. And why? Because we are not supermen; we are not Doc Savage, equipped to handle the unusual.

This is what I'm talking about regarding the plight of the common man in science fiction. You've probably noticed by now how few of these stories are about actual "heroes." "Who Goes There," of course, had a Doc Savage look-alike in McReady and their enemy is of the caliber of Grendel, or Grendel's mom, straight out of Beowulf. This is a monster worthy of Doc Savage.

Illustrated by Randy Grochoske

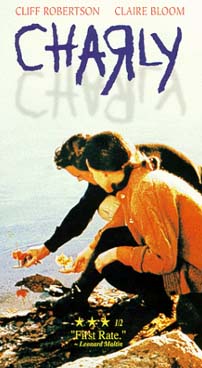

But World War II showed us that the common man could be an uncommon hero, and the 1950s were rife with stories about ordinary people caught up in extraordinary situations. The Sheckley story is one of those, and so too, is Daniel Keyes' heart wrenching "Flowers for Algernon." This is the only story Keyes is known for today, but it's a doozy. The emotional impact of the story comes from its narrative strategy-the diary of a retarded man as he evolves into something of a mental giant. The novella version received a Hugo in 1960 and the novel version in 1966 received the Nebula Award for the best novel of the year. "Flowers for Algernon" was made into the movie, Charly in 1968.

I also chose "Flowers for Algernon" for your text because it's one of the few stories in the field that makes use of a narrative technique rarely employed in the genre. Tales told in journal or epistolary format go all the way back to the 1700s to writers such as Daniel Defoe and Samuel Richardson, later to be used by Poe and Hawthorne. It's a strategy that has its own built-in sense of verisimilitude and we can actually see the changes as they happen to Charly in "Flowers for Algernon." You might also take note here of the similarities to Frankenstein where the monster is allowed to tell part of own tale. "Flowers for Algernon" is one of science fiction's clear masterpieces.

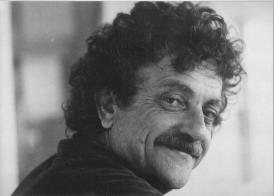

Perhaps the greatest satirist since Mark Twain was Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. Vonnegut's stories have an eerie stylistic simplicity, masking, as it does, a devastatingly sharp wit that has yet to be equaled. Curiously, Vonnegut's "Harrison Bergeron," though written in 1961, seems more relevant to life in 21st America than the early Sixties. Today, it seems, everyone has fallen victim to some form of "political correctness" or another. The 1990s especially saw litigants in courts across the land, claiming one kind of abuse or another at the hands of someone who probably had no idea that they had said or done a thing. It was just the tenor of the times.

It was an era where you had to be careful what you said or did, lest it might offend someone . . . someone who would take you to court at the proverbial drop of a hat . . . someone who would love to put you in jail simply for holding a divergent opinion--

---or perhaps not belonging to the "correct" religious faith.

And don't think for a minute that it still cannot happen. Don't think that there aren't people out there who don't like you (this is primal man's fear of "the other") and feel that it is their right to change you. (Mostly because one or two of their religious leaders a long time ago said that it it is important for them to do this for the good of mankind.) Some of these people are presently hiding in caves in the mountains of eastern Afghanistan; others wear suits and ties (and nice dresses) and work on Madison Avenue. They don't like you either. Well, they like your money. But they'd still love to change the way you look and think about yourself. (So would Pat Robertson, come to think of it.)

In fact, to offend anyone for any reason was a no-no in the Eighties and Nineties. "Harrison Bergeron" is a perfect example of the morals of a society out of control; society itself has become the Frankenstein monster.

In an effort to make everyone feel good about themselves (or not to feel bad for what they, in fact, are), we've made it so that anyone who excels is viewed with contempt and eventually censured, especially anyone who's thought a bit deeper about the nature of reality or who might have a more informed opinion or who might have just "gone the extra mile" to become the person they wanted to be, someone exceptional who might embarrass us simply by being around. Imagine what life would be like without them showing us what can be done? Here are two of my favorites.

Madonna Ciccione |

Muhammad Ali |

|---|

* * *

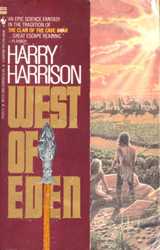

The final story in this section is by Harry Harrison, an extremely prolific writer of a wide range of science fiction stories who is best known today for his alternate history Eden novels where dinosaurs never became extinct and the intelligent ones have to interact with what few humans there are in the world. Harrison's stories also had elements of satire in them, but he is not considered a satirist the way Vonnegut is. Harrison kept his science fiction close to the Campbell mode of believability and often has come up with stories of a sadly tragic nature. "The Streets of Ashkalon" is one of the saddest science fiction stories ever written.

Indeed, you will have noticed by now that many of the truly great SF stories do not have happy endings at all - like mainstream literature. Go figure. But for as bitter as "The Streets of Ashkalon" is, nothing will prepare you for the absolute hilarity of Harrison's classic anti-war novel, Bill, The Galactic Hero, which is a slam at Robert A. Heinlein's pro-military stance in Starship Troopers, a juvenile novel that doesn't really criticize the military the way many people left of center thought books of that era should - the era being the beginning of America's escalation of the Vietnam War.

Echoes of America's involvement in Vietnam only magnify one of the important themes in science fiction which has to do with the impact humans have on lesser (here read: alien) cultures. This theme appears throughout the various Star Trek incarnations and is called the Prime Directive. Star Trek is also a Cold War product and Gene Roddenbury was also not a fan of America's involvement in Vietnam.

But while Gene Roddenbury had his Star Trek writers keep Kirk, Picard, Janeway, and Archer out of the affairs of less advanced cultures, the rest of the science fiction world was not so hesitant. And usually when humans interacted with other creatures the results are sadly tragic. "The Streets of Ashkelon" is a bitterly ironic story that actually gives credence (of a kind) to the spirit of the Prime Directive. Without it everybody loses, even humans.

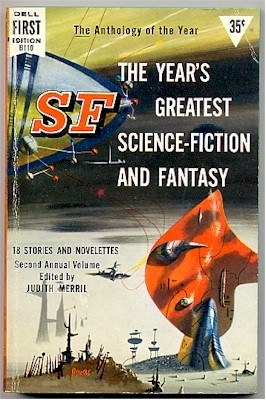

Another important factor in the growth of the science fiction field in the 1950s is the rise of the science fiction anthology, both in paperback and hardbound formats. Anthologies allowed for the greater proliferation of stories that were deemed exceptional for the previous year (or fit a particular editorial format, such as stories about robots, or time travel, etc.). This way, authors were able to earn a little bit more money and keep their names current in the minds of the reading public. However, this was also the era of the superb science fiction editor as well, and important editors were legion. Among them were Martin Greenberg, Damon Knight, August Derlith, Geoff Conklin, Frederick Pohl, the aforementioned Donald Wollheim, then later on the extraordinarily influential Judith Merril whose Year's Best SF routinely contained some of the best reading on any planet.

|

Judith Merril |

These books continued to chip away at John Campbell's influence over the field of science fiction, even if they always contained a story that originally came from Astounding. Campbell nonetheless published excellent science fiction until the day he died.

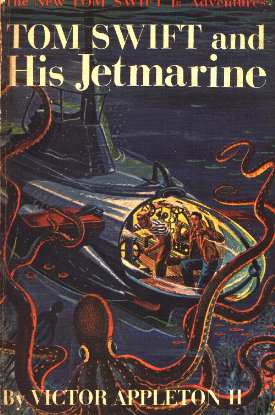

One final publishing phenomenon in the Fifties was the rise of juvenile or young adult SF book series. Grosset and Dunlap created a very popular Tom Swift, Jr. series based on the Tom Swift, boy inventor series of the 1920s. These new Tom Swift books were very much in the science fiction vein, complete with helpful aliens. Like his father before him, Tom Swift Jr. came up with rather unique inventions, many of which have yet to be invented. Still, the adventures were straight out of pulp science fiction and furthered the notion of the scientist-as-hero, common to the Twenties and Thirties.

|

Click on any image for a link to a Tom Swift, Jr. site.

Also in the 1950s, the Winston Publishing Company published a series of juvenile science fiction novels that were widely read yet widely panned by critics. These books were simplistic and undemanding and are today very popular among book collectors nationwide. For example, a good copy of British writer Paul Capon's The World At Bay (Winston 1953), a generally wretched novel by anyone's standards, sells anywhere from $100 to $300 in rare book auctions. Go figure.

But for as maligned as this Winston series was, they also published excellent novels and some of them first novels by some of the greatest names in science fiction. They published Poul Anderson, James H. Schmitz, Ben Bova, Donald A. Wolheim, Raymond F. Jones, Arthur C. Clarke, Chad Oliver, and Lester Del Rey. It should also be emphasized here that during the 1950s both Asimov and Heinlein wrote for the juvenile science fiction market as well. It was a good way to make a living, even if the critics grumbled.

Click on either image to a link to a Winston Science Fiction fan site.

But the 1960s are now upon us and by the end of the decade, everything will have changed. And I mean everything.