SECOND LECTURE

From the film of H.G. Wells' Shape of Things to Come.

We are now at the point where recognizable modern science fiction begins. Certainly, by the time H. G. Wells dies in 1946, science fiction had come a long way. It had its name by then, courtesy of Hugo Gernsback who coined the term somewhere during 1929. Gernsback, whom we will explore in depth a little later on, had even characterized what he thought of as science fiction as "fiction written in the mode of H. G. Wells." So even by the late 1920s Wells' influence over the yet-to-be-named genre was quite evident.

But how did we get from The Time Machine in 1895 to the strange literature of the 1920s?

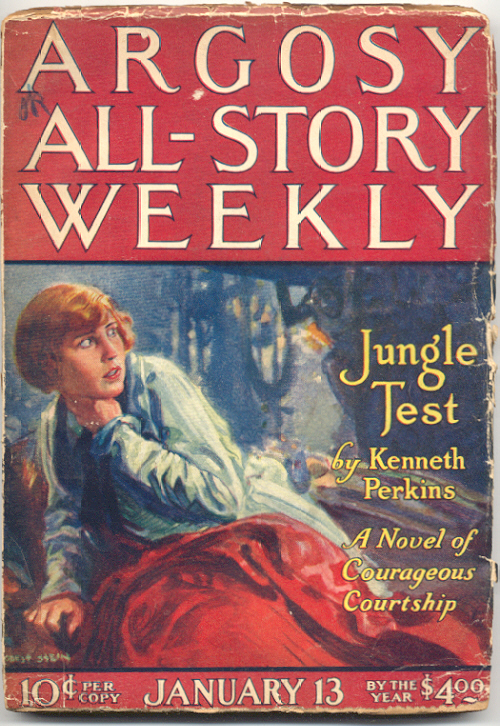

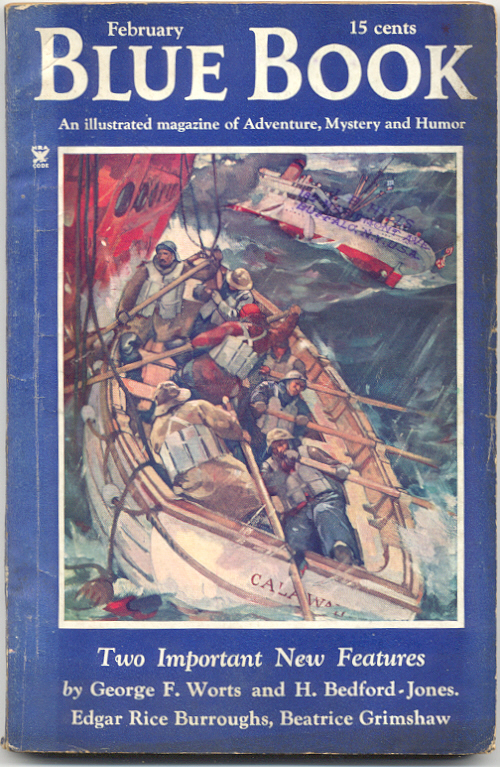

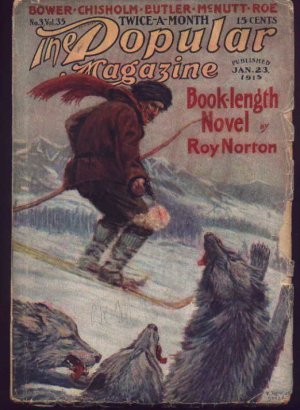

It wasn't until the late 1890s and the invention of linotype printing that true "popular" fiction came on-line for the masses. This is the beginning of the reign of the great "pulp" magazines. It was in this very inexpensive form of pulp publishing that science fiction was able to reach-and some have said-bulid a wider reading audience. In fact, all of the genres of popular literature (at least as publishers presently distinguish them) began in the era of pulp magazines, which ran roughly from the 1890s to the early 1950s.

|

|

|

The pulps were the first magazines aimed at specific demographics (boys, girls, men, women, etc.) or clear subject genres (the western, the mystery story, war, etc.) rather than a general fiction market. One of the greatest pulp magazines, Argosy, started out as a general fiction magazine, but quickly became a purely "adventure" magazine, aimed at young boys and young adult males, with stories that took place all over the globe. These were often written in the tradition of Jack London and Joseph Conrad but always stressing action. Indeed, Rudyard Kipling's "As Easy as A.B.C." and E.M. Forster's "The Machine Stops" will appear in the very magazines that the common consumer read for fun. Both were meant as satires and would have been fully appreciated in their times as taking a poke at the future they knew was just on the horizon.

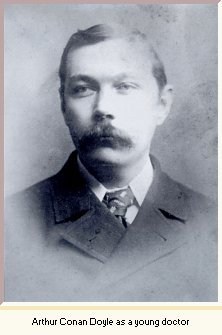

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Creator of Professor Challenger and Sherlock Holmes

One of the first authors to emerge in this new market in England was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930). Originally a country doctor, Doyle found success in publishing by writing stories in his spare time about about a detective named Sherlock Holmes. Doyle wrote at a time when the tales of Edgar Allan Poe and Jules Verne (and a host of lesser luminaries) had sparked interest in all manner of stories of exotic locations and bizarre adventures. Professor Challenger is Doyle's other great creation and The Lost World is part of a sub-genre of Victorian science fiction called the "scientific romance". Most of what is now early science fiction can be slotted into the definition of scientific romance in that these stories were generally light on scientific possibility (time travel, death rays, dinosaurs, etc.) and long on adventure. It started in Britain but quickly moved over to America. Much of that leap had to do with the availability of fiction magazines.

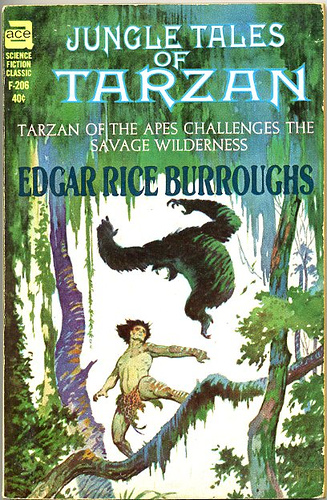

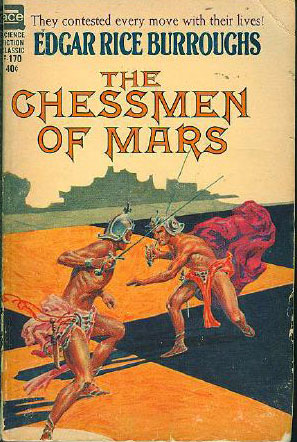

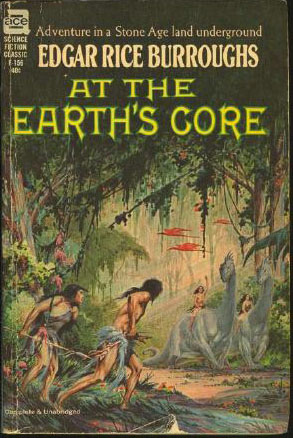

The most significant of these publications were those published by Frank R. Munsey starting in 1895. One of these was All-Story Magazine, and in 1911 Munsey published Edgar Rice Burroughs' At the Earth's Core, the first of the Pelluciadr novels, then in 1912, he published Burroughs' Tarzan of the Apes, then after that came the first of the Mars books (or books about the planet Barsoom) A Princess of Mars. These novels, and those by others ranging from the late 19th century to the very middle of the 20th century, are considered today to be what's called "scientific romances" and not science fiction as such--or even fantasy. More on this later.

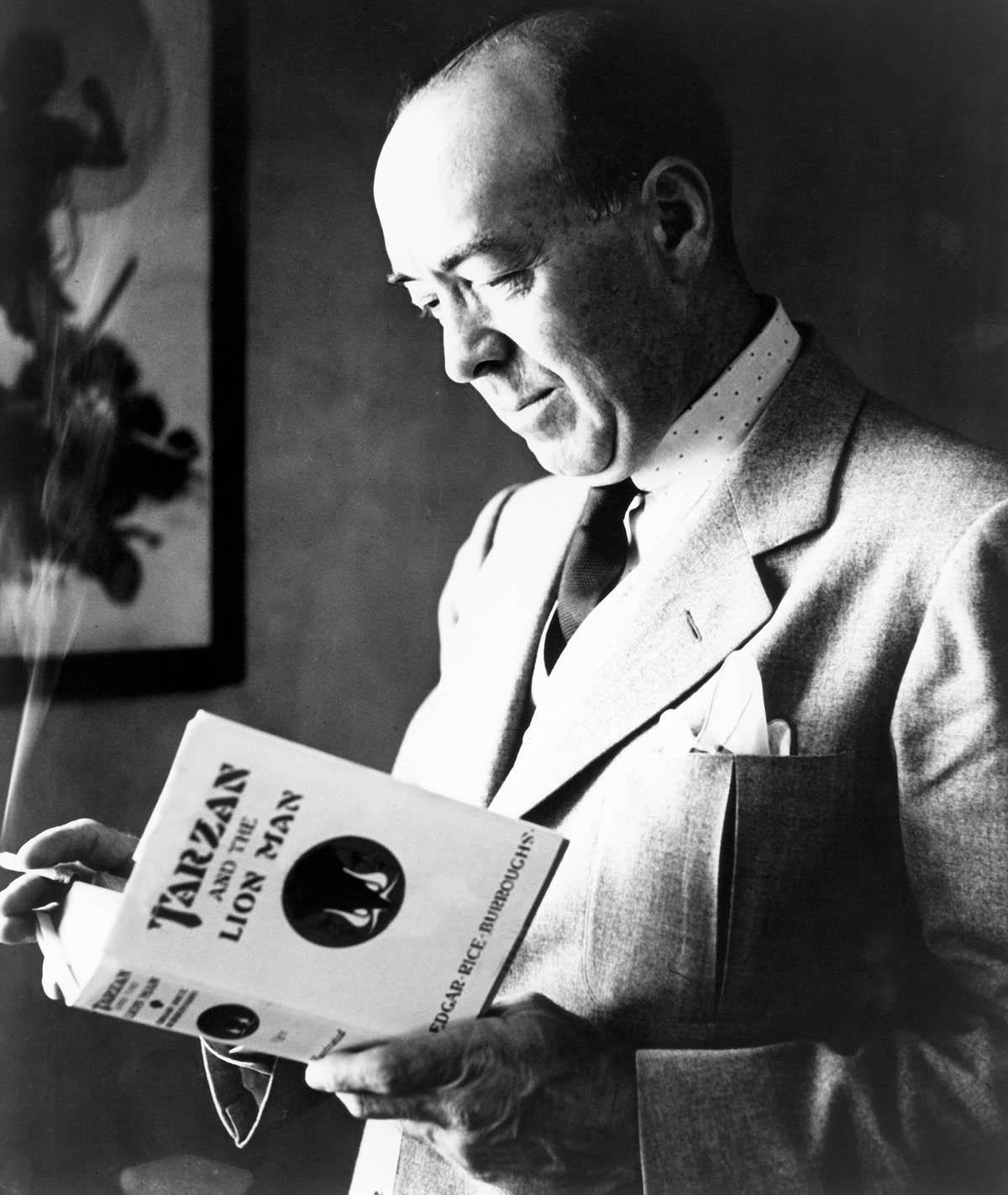

Edgar Rice Burroughs

1875-1950

|

|

Burroughs, by all accounts, was the best-selling American author of the Teens and the Twenties, outselling Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and Faulkner, combined (but this in no way suggests that he was the better writer). If the great American novelists of the Twenties sold in the tens of thousands, Burroughs sold in the millions. Burroughs' stories at first came out serially in the likes of Munsey's All-Story Magazine and others in the Munsey line, then were printed in the form of books, finally made into movies, comics, serials, and a television series. Today these are seen as more in the vein of fantasy adventure. Even so, in his day Burroughs was astute enough to place his stories in locales and parts of the globe that readers of Verne, Wells, and Jack London would find familiar. A history of science fiction isn't complete without some significant mention of Edgar Rice Burroughs and the rise of the pulp era which he helped foster.

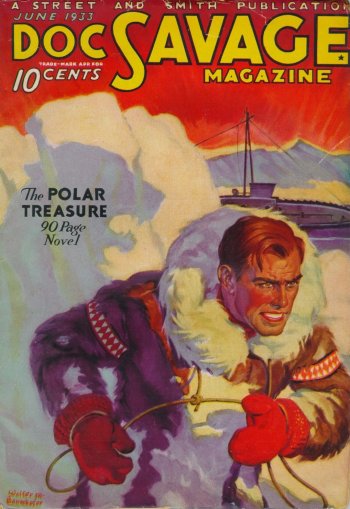

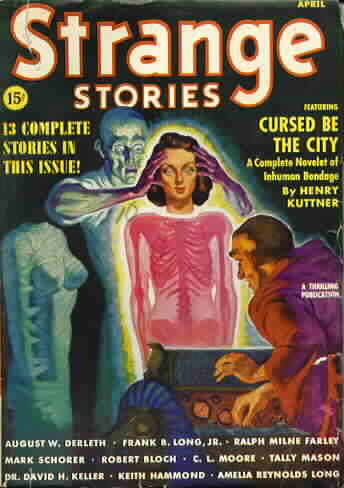

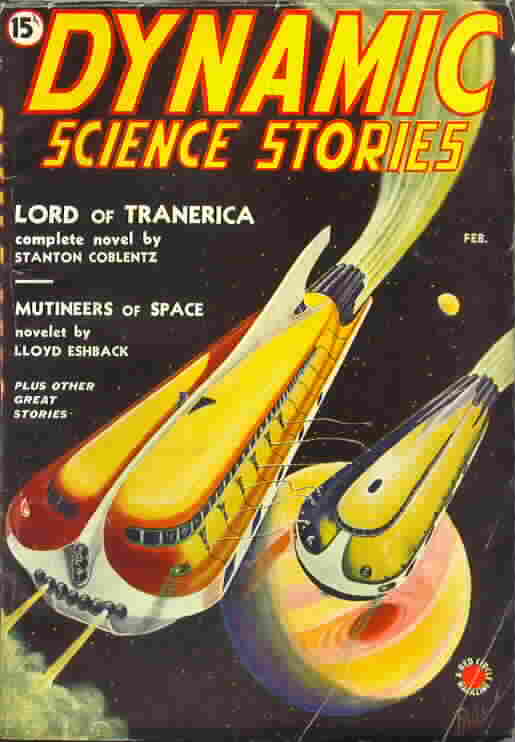

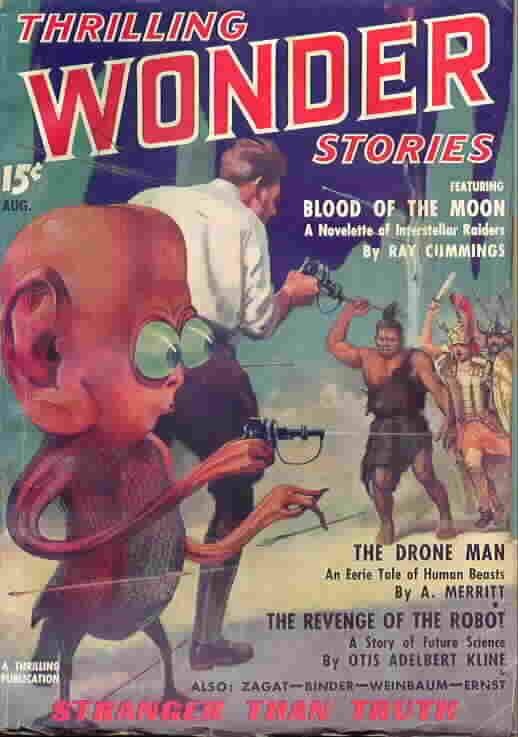

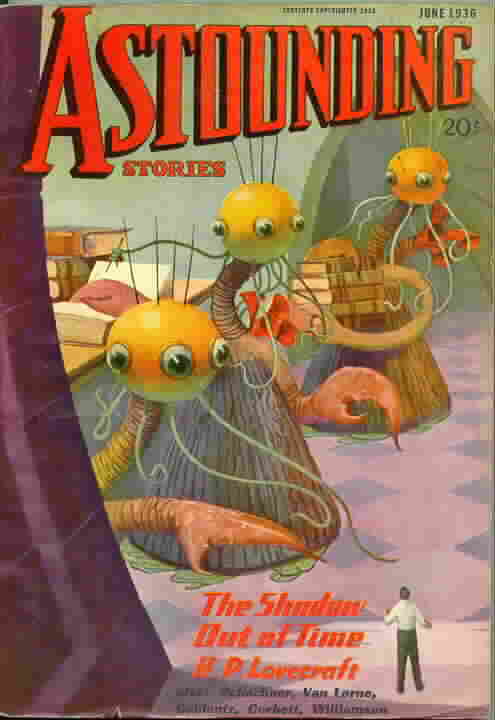

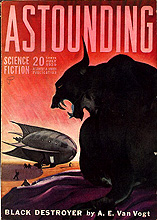

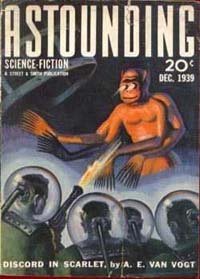

The 1930s was the heyday of the great science fiction pulp magazines. Among these were Planet Stories, Amazing Science Fiction, Astounding Science Fiction, Startling Stories, and Thrilling Wonder Stories.

|

|

|

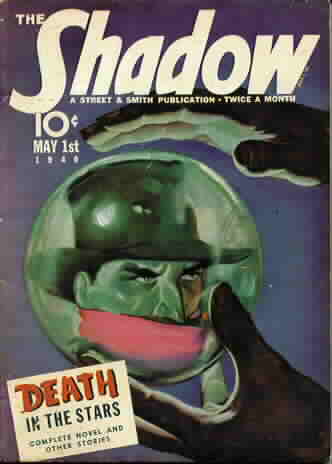

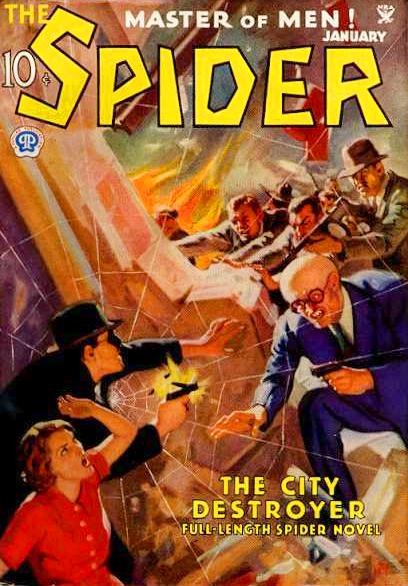

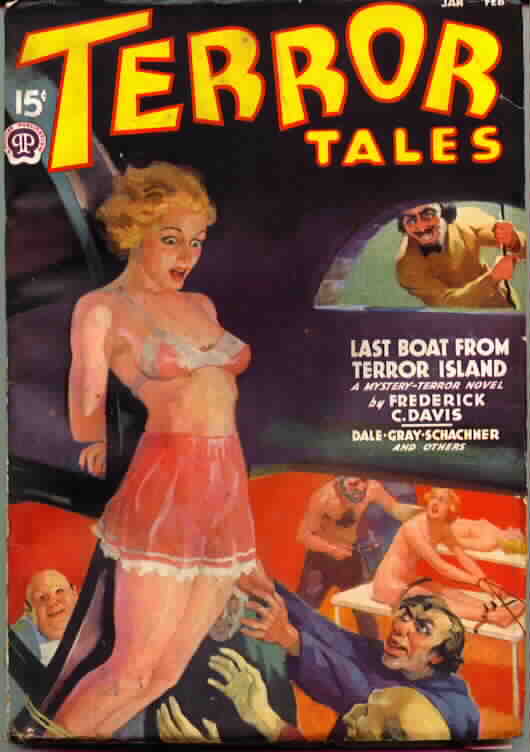

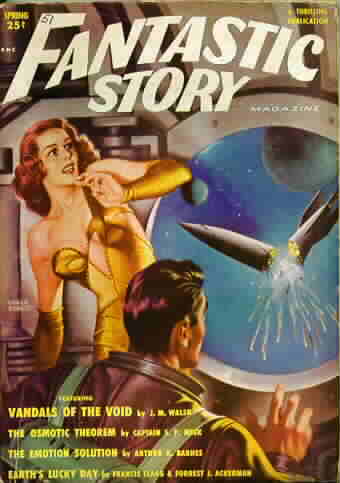

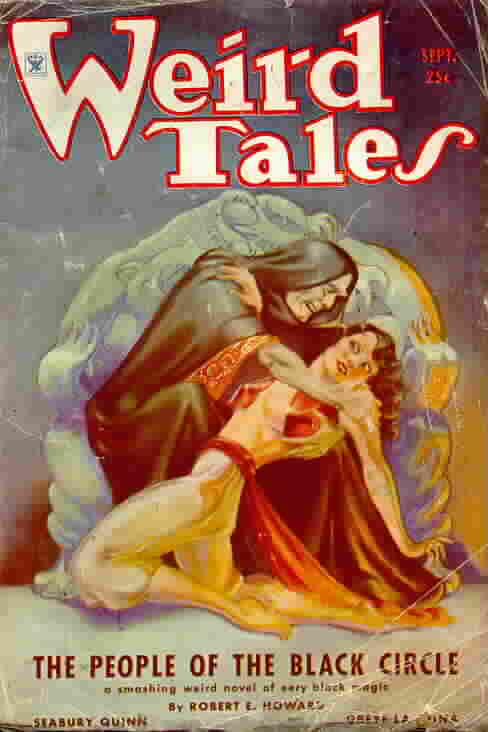

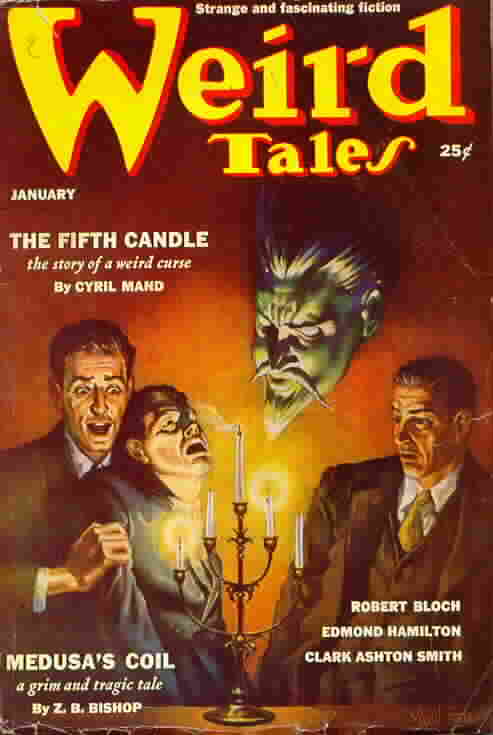

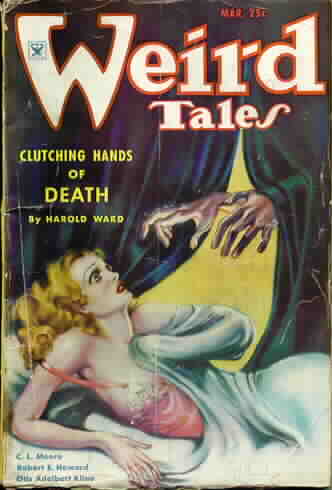

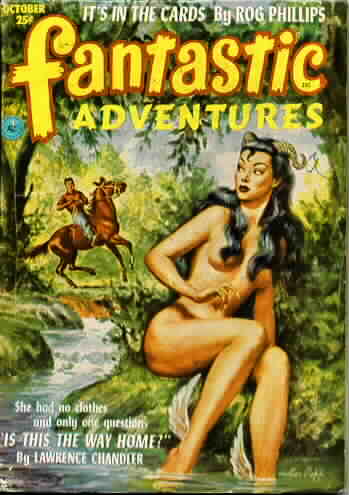

The pulps were known for their garish covers of monsters and women in distress. But they are also well known for their very colorful covers. Pulp magazines got their name from the use of extremely cheap paper made from simple wood pulp. These were magazines that were meant to be "consumed" and when you were done with them, you threw them away. These were among the very first artefacts of America's then-evolving throwaway culture. It became just another part of the "mass production" philosophy that Henry Ford was in the process of inventing. Pulps, like newspapers, came out fast and furious, and by the time World War II began in 1939, over 900 different pulp titles had come into existence.

Indeed, pulps were the precursor of the paperback book. Most pulps, especially in the 1930s, often touted a full-length novel in every issue. The hero pulps of the 1930-Doc Savage, The Shadow, The Spider, The Avenger, Nick Carter, G-8, Operator 5, etc.-each had a novel and at least three stories in every issue.

By the late 1940s all the fiction genres we know today--the western, the romance, the mystery, science fiction and fantasy--were all well established by World War II. Indeed, these stories have changed little since then, a sign of their popularity.

It should also be pointed out that pulps gained their popularity because there were very few other entertainment venues around. Though radio was invented in 1895, its real popularity did not take hold until the mid-1920s, where radio shows often broadcast live and featured news, music, and very popular serials, also separated into distinct genres-the western, the detective story, the romance. Movies (replacing touring Vaudeville shows) soon appeared thereafter. It was a heady time, driven by invention. In fact, cinematographer George Melies, a Vaudevillian magician by trade, made the first science fiction movie in 1902 called A Trip to the Moon, complete with special effects . However, radio remained the cheapest venue for family entertainment for a half-century until television sets became available for domestic use in 1949.

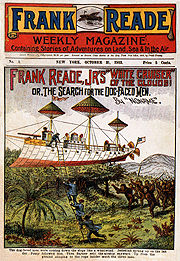

Just before the pulps came onto the scene, "dime novels" began to appear in both America and throughout Europe in the 1870s. Westerns and boys' adventures were the most popular dime novel at this time, but close on their heals came novels that were in the mode of Jules Verne. These were so-called "invention" stories, the most popular of which were the fictional adventures of Frank Reade, boy genius--very much part of the "scientific romance" genre. Reade was the imaginative product of Harry Enton who based his character on that of Horatio Alger, off in search of adventure in his strange vehicles. Harry Enton's first book was Frank Reade and his Steam Man of the Plains, published in 1876, a time when steam anything was all the rage, especially in America.

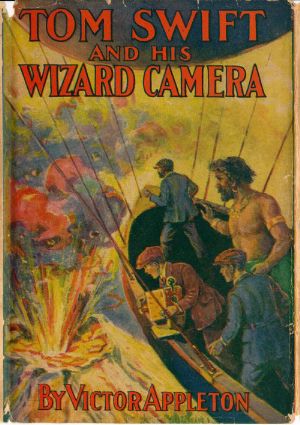

When Harry Enton got tired of writing what he thought of as "juvenile" books, a man named Luis P. Senarens was commissioned to write about Frank Reade's son, Frank Reade, Jr. The popularity of this series eventually lead to the even more popular Tom Swift novels, written by Victor Appleton (who was in actuality a man named Howard R. Garis). The Tom Swift books were part of the publishing empire of Edward Stratemeyer (1862-1930) who published a wide range of what we would now call "young adult" stories. Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys were among the other popular series that Stratemeyer later on published. Every one of these series endured for decades and were immensely popular.

So science fiction stories (in hardbound form) that were about inventors and their inventions persisted well into the 1930s, mostly because this also happened to be a period of extraordinary advances science and technology. The scientist as hero began to appear as a popular motif in pulp fiction. Part of this had to do with the fact that real scientist heroes did exist. Remember that this is the heyday of the great inventor: Thomas Edison (1847-1931), Albert Einstein (1879-1955), Charles Proteus Steinmetz (1865-1923) and the much overlooked Nikola Tesla (1856-1943), to name just a few. The public viewed these people with the kind of celebrity reverence we now give rock stars. Their names were well-known, and so were their exploits.

Nikolai Tesla in a famous double-exposure photograph.

However, it was the popularity of radio technology that jump-started the science fiction genre in pulp magazines. Hugo Gernsback (1884-1976) was a Luxembourg-born writer and editor who came to America in 1904. His interests were in all things electric; his heroes were inventors, especially Edison and Tesla. Gernsback's first magazine publication in 1908 was Modern Electrics, devoted mostly to radio technologies. A short time later Modern Electrics became Electrical Experimenter and Gernsback started publishing bits of his own fiction in Electrical Experimenter as filler. Gernsback eventually began publishing Science and Invention Magazine in 1920, a much more ambitious journal that aimed for a wider audience than just boys interested in building crystal radio sets in their rooms. In Science and Invention his fiction and that of others began to appear with greater regularly . However, in the August 1923 issue of Science and Invention, Gernsback published only fiction, no articles. This fiction he called scientifiction, and were stories, he claimed, to be in the mode of H. G. Wells.

This one issue of Science and Invention was so popular that in 1926 Gernsback created Amazing Stories, the first true magazine devoted to the new fictional genre called "scientifiction." Later, in the early Thirties, Gernsback revised the term, now calling this new literature "science fiction." Later in his career Gernsback went on to publish Air Wonder Stories, Science Wonder Stories, and Scientific Detective Monthly.

|

|

|

Though these magazines were successful in their day, Gernsback eventually lost financial control of his publishing empire and many of his magazines, with the exception of Amazing Stories, perished. In fact, few pulps survived the paper shortages of World War II and the appearance of comic books. The fledgling National DC company (owners of Superman and Batman) and the early Marvel lines, starting in 1939, took away many of the younger readers who, a decade earlier, would have been devoted pulp fans. But in the science fiction genre itself, Gernsback's influence had endured long enough for science fiction to take root permanently in the American culture.

What pulps of the late 1920s and early 1930s gave readers stories that emphasized the "gosh-wow!" aspect of new inventions. From these new inventions came (what are now) standard science fiction tropes and icons, whether or not the actual science within them made sense. It's from this period, I have chosen the Edmund Hamilton story in your anthology, "Fessenden's Worlds" which was originally published in Weird Tales in April of 1937. Hamilton was a prolific pulp writer during the Great Depression and his science, if we can call it that, often took back seat to incredible stories written in a florid prose style. Hamilton, along with E.E. "Doc" Smith and Jack Williamson, fostered the "space opera" story, complete with giant spaceship armadas and exploding planets (tropes of which persist in the Star Wars movies). They were just the stories that would capture the mind and imagination of teenage boys in the Great Depression (and quite a few are still readable today). Stories by these authors often appeared in several magazines in any given month throughout the Thirties. They were often written in a single draft, put into the mail and forgotten about as the next deadline (or meal) approached. It was, for some, a good way to beat the gloom of the Depression years.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

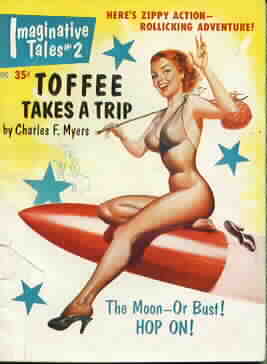

Weird Tales often published stories like "Fessenden's Worlds" that were borderline fantasy or pseudo-science fiction. Indeed, this taint of "pseudo-science" has stigmatized the entire science fiction field, especially regarding any sort of academic acceptance of the field's artistic legitimacy. None of this was helped by the cheesy covers of women in distress (and, of course, wearing very little clothing) that continually appeared on the science fiction pulp magazines from their inception well into the 1950s. Covers like these still make people cringe.

|

|

|

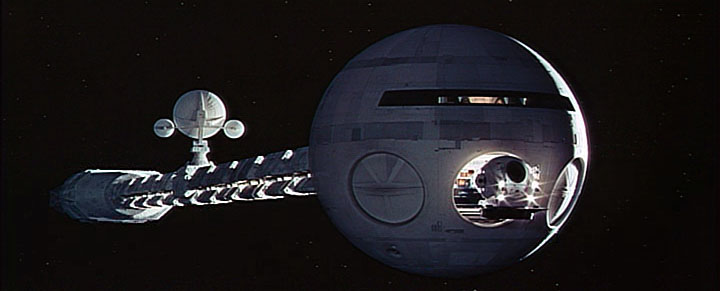

Movies and serials that perpetuated racial, gender, and genre stereotypes didn't help the field much either. Both of the Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon movie serials in the 1930s, popular though they were to young audiences, nonetheless gave science fiction an ongoing aura of tackiness that only began to change in the 1970s. Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) helped bring that change to cinema in a very dramatic way.

However, during this period (approaching 1937 and the important career John W. Campbell, Jr.), avoiding the pulps altogether we find science fiction appearing in novel form, and coming not only from America, but from Europe and England as well.

At this time as H.G. Wells continued his writing career and was very much a public figure. Aldous Huxley (1894-1963) began to publish a number of significant extrapolative works, notably Brave New World (1932) that contained many now-standard SF tropes, most notably cloning and the use of soporific drugs to keep the population happy. American Nobel laureate Sinclair Lewis (1888-1951) wrote perhaps the first alternate history in It Can't Happen Here (1935) about an overthrow of the United States government during the Great Depression, something both Lewis and J. Edgar Hoover believed could happen because of the wave of poverty that had swept the world. Indeed, fantastic literature seemed to flourish in the Great Depression because of this widespread economic downturn. Certainly millions of people in this country and abroad were ready for stories of an escapist bent, even if much of their subtext might be based in reality.

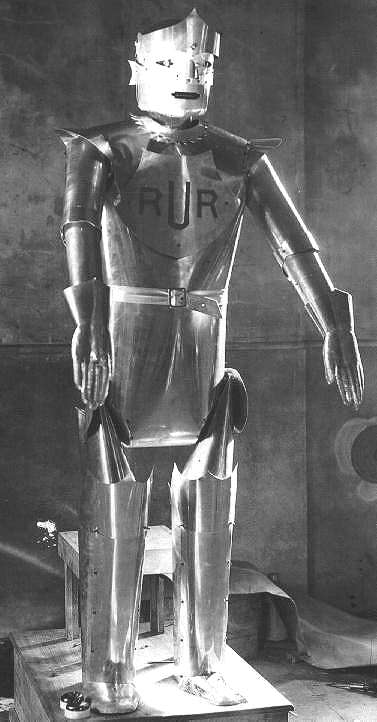

In

1920, Russian writer Yevgeny Zamyatin (1884-1937) wrote We, an

anti-utopian novel that is a powerful condemnation of science and technology

(which was, in turn, a powerful condemnation of the utopian visions of

Joseph "The Plowman" Stalin). Also in 1920 Karel Capek presented

his most famous play, R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots) which

gave the world the word "robot" for the first time. Another

British writer, Olaf Stapledon (1886-1950) began writing some of the most

visionary novels ever written. His most famous are The Last and First

Men (1930), Odd John (1935), and Star Maker (1937).

In fact, Odd John is the first novel about a mutant superman whose

very existence alone threatens mankind. (This is the conceit behind Marvel

Comics' X-Men series, but Stapledon thought of it first and his mutants

have some very strange powers indeed.)

One of the stage robots from the play R.U.R.

But it needs to be pointed out here that none of the works referenced in the previous paragraph were ever published as science fiction, anywhere, under any conditions. They still aren't. Nevertheless they are still considered to be well within the conceptual parameters of just about anyone's definition of science fiction (especially mine). These are books that explore the possible futures open to humankind, now that we've got all manner of advanced technologies.

On closer examination, these stories are essentially horror stories and you'll recall that it's this gothic element, the horror element, that makes science fiction, in Brian Aldiss' belief, so significant. And perhaps the greatest of these "non-SF" science fiction novels of this period is George Orwell's 1984, whose terrifying vision of the future is just as relevant today as it was in 1949, the year it was published.

Overall, it seemed that, by the end of the 1930s, American science fiction was bogged down in cheesy pulp magazines whose covers were blazoned with men in tights clutching blondes in their arms and shooting purple beasts somewhere on the moons of Jupiter. Goofy Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers serials didn't help much either. This would soon change, however. Science fiction was about to become serious again.

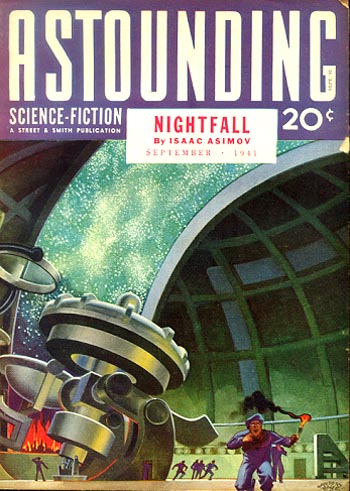

Hugo Gernsback's influence on science fiction was largely gone by 1937 when John W. Campbell Jr. (1910-1971) took over the helm of Astounding Stories (soon to become Astounding Science Fiction). Campbell started writing in his teens and came up through the pulp ranks, publishing stories of "super science" in Gernsback's own Amazing Stories. By the time Campbell took the helm of Astounding Stories in 1937, he had matured enough as a writer and as a social philosopher to begin demanding a different standard of writing from his stable of writers.

As such, John W. Campbell Jr. is generally credited with formulating or characterizing science fiction as it's understood today. He is also credited for ending the era of the "scientific romance" or at least relegating it to a branch of adventure fantasy such as the Tarzan novels or the Burroughs novels that take place on Mars or Venus.

Campbell first of all demanded a no-nonsense approach to both real and extrapolated science. The science had to sound reasonable and the men and women who were the stories were about had to behave in a credible way. In effect, Campbell demanded a keen sense of verisimilitude from his stable of writers. None of this Captain Future/Buck Rogers "gosh-wow!" stuff. Secondly, he demanded a higher level of professionalism in the actual prose his authors produced and this included verisimilitude in all aspects of how men and women would actually behave even under the most bizarre of circumstances. Campbell demanded that his writers respect the intelligence of the average reader of Astounding Science Fiction while writing as well as they could.

John W. Campbell, Jr. by famed artist Kelly Freas.

And it shows even in his own fiction. "Who Goes There", published in 1938, was Campbell's own masterpiece of scientists at work. Campbell deftly portrays a group of different scientific types trying to solve the problem of an alien menace among them.

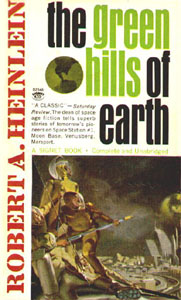

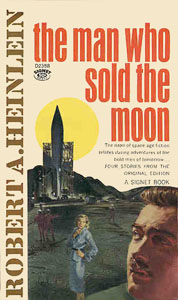

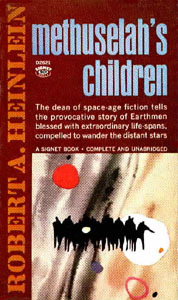

As an editor, Campbell is also responsible for starting the careers of Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon, Lester Del Rey, Murray Leinster, Henry Kuttner, Lester Del Rey, and A. E. Van Vogt, while helping along others who began in other pulp genres such as Jack Williamson, Clifford Simak, and L. Ron Hubbard. Campbell is credited with co-creating Asimov's Three Laws of Robotics in Asimov's "Robot" stories and for giving Asimov the basic idea for his "Foundation" stories which would eventually become the Foundation Trilogy. He also gave guidance to Robert A. Heinlein when many of Heinlein's stories seemed to be taking place in the same universe. All of these stories, plus one novel, can be found in Heinlein's seminal work, The Past Through Tomorrow (1967). Campbell also published the first (largely positive) article on L. Ron Hubbard's nascent Dianetics ideas in the late 1940s. Heinlein, however, was a star from the beginning until he left off writing to join the war effort.

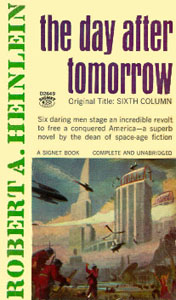

For the most part Campbell saw science and technology in a positive light, as long as humans behaved themselves. But Campbell did not limit his authors to mere science and technology (mere gizmo SF) as Gernsback had. Campbell encouraged his stable authors to explore aspects of future politics and social change in the pages of Astounding, something Gernsback wasn't interested in. Campbell, a child of the Depression, had a keen suspicion of governments and bureaucracies, and you can see how some of this rubs off in several stories in your anthology. In fact, Campbell saw that a simple idea all on its own could become something like a Frankenstein monster and not just ideas floating around in science and technology. Ideas such as the rightness of any religion or the tyrannies of any majority can be very dangerous ideas indeed. In fact, a very bad idea can bring a nation to its knees and a bad philosophy can ruin an age-old institution, any age-old institution. Campbell even encouraged Robert Heinlein to write a novel called the Sixth Column (published in 1941 under the pseudonym Anson McDonald, then in 1951 as RAH with the title The Day After Tomorrow), wherein a bogus religion overthrows a dictatorship in a future USA. The fear of larger bureaucratic systems stomping on the average individual was a commonly held notion in the 1930s because people alive at that time had actually seen a small group of men in 1929 turn Wall Street into a casino and the government of the United States nearly collapsed because of the outcome.

|

|

|

Heinlein did very well by Signet Books in the early 1960s with some of the most evocative covers the field had yet seen in paperback publishing.

Both Campbell and Heinlein were libertarians at heart. They believed in the primacy of the individual and held an enormous suspicion of large-scale institutions, religious, political, you name it. Campbell knew that governments were prone to get out of control (or display no controls whatever, as in the aftermath of the crash of 1929 that precipitated the Great Depression) and the first thing that usually went when governments collapsed were individual rights, or civil liberties. This goes for religious institutions as well. Indeed, "They" can be taken as a metaphor of them versus us (or in case of the story, the lone individual). It should be noted that Campbell never let his writers pick on any one church or religion even though later science fiction writers would later start pointing fingers and naming names. One such writer will be Walter M. Miller Jr. whose A Canticle for Liebowitz of 1959 will take a few pokes at the Roman Catholic Church, or at least its enduring medievalism and its mandate on utter obedience. James Blish's A Case for Conscience (1958) will tackle the simple arrogance of human religion, asking questions about aliens and Christian redemption.

It should come as no surprise then that Astounding's best years were from 1939 to 1945, which neatly parallels World War II, a time when civil liberties were, by necessity, suspended. This also was a time of a budding "can do" attitude in most Americans as the country entered the war and put our physical and mental muscles to work. Campbell had faith enough in scientists and the "hero" mentality that his stories were filled with optimism and the belief that with the right kind of mental effort (as in a chess game, for example) a solution could be found. Campbell, as such, advocated the "conundrum" story. These were stories were a technological fix was needed to resolve a crisis. Most of the writers appearing in Astounding wrote conundrum stories. But Campbell's greatest writer of "conundrum" stories was Isaac Asimov.

Asimov, a scientist at heart, wrote stories that focused on problems of a technological kind. Later in his career he would explore the societal ramifications of technological problem, but in the early 1940s he dazzled his readers with his immensely popular "Robot" stories. Robots had already become a familiar conceit with science fiction fans; they would have known of robots from Fritz Lang's Metropolis with its gorgeous female android. They would have remembered the 1939 World's Fair and the robot of the Futurama and the wonders they seemed to foretell.

Asimov's robots, however, were different. The Robot stories had specific rules of engagement. Both Campbell and Asimov came up with "Three Rules of Robotics" and all of Asimov's Robot stories operate within the range of these rules, rules that were quite like the rules of chess, beyond which you could not stray. The Rules are:

1) A robot may not harm a human being or through inaction allow a human being to come to harm;

2) A robot must obey the orders of a human being except where they come into conflict with the First Rule;

3) A robot must protect its own existence except where it comes into conflict with the First or the Second Rule.

.jpg)

Therefore, Asimov's Robot stories became scenarios where a robot found itself in conflict with one or more of the Rules and, sometimes with the help of a human, managed to overcome the crisis without breaking any of the rules. Indeed, any of the Robot stories can be seen as archetypal Campbell stories centered around paradoxes and science-based solutions. Asimov's early reputation rested on the popularity of these stories, and so influential were they that other editors would not let their writers write about robots unless they obeyed Asimov's Rules of Robotics. This, of course, no longer applies. Just ask the Terminator.

Asimov also had a flair for the larger problems of a vast galactic society and these are found in the stories that lead up to the Foundation Series. Speaking generally, Asimov's characters always operated with the confines of these large civilizations; Robert Heinlein's characters were often renegades from those societies. A good example of Asimov balancing the life of science with the facts of historical change is found in the story "Nightfall". Here Asimov speculates on how a society might change if its very belief system was shown to be in error. The change is horrific and, as in most science fiction, functions as a metaphor for our own scientific arrogance.

Another immensely popular writer of the Campbellian stable was A.E. Van Vogt. Van Vogt's science fiction tended to lean toward space opera and worlds filled with all kinds of peculiar creatures, but he also had a political streak in him that bore a resemblance to some of the ideas embraced by Robert Heinlein. "The Weapon Shop of Isher" stories detail a repressive society where one man (with a gun and some bizarre loops in time) comes to challenge it. Van Vogt's stories, though, were more complexly written (sometimes to a fault) than those of Heinlein and drew from adventure elements common to the freewheeling action pulps of the 1930s before Campbell changed all that.

Harlan Ellison presenting A.E. Van Vogt with the Grand Master Lifetime Achievement award.

Indeed, one of Van Vogt's best novels is actually a collection of four novelettes called The Voyage of the Space Beagle (1939-1943) and is rumored to be the inspiration for Gene Roddenberry's Star Trek. Scientists of the Space Beagle travel hither and yon and encounter a wide range of exotic and very memorable alien beasts.

|

|

|---|

As mentioned earlier, many critics have suggested that the pulp era, and Hugo Gernsback in particular, created a "dumbing down" of science fiction. Since this also occurred in an era of grade B movie serials that were very clearly dumb, this has always been an impression hard to overcome. But a close reading of science fiction of the late 1930s, particularly once Campbell takes over Astounding, will show the reader that Campbell was the one person responsible for bringing a more studied seriousness to the genre. Not all science fiction ends unhappily in the pages of Astounding. But the field matured profoundly under Campbell's influence. Campbell showed that science fiction was an excellent proving ground for the exploration of myth, morality, and the things we can expect the future to bring to us---happily or sadly.