HOME | PURPOSES | TEAM | PARTNERS | THEORIES | MEASUREMENTS | PUBLICATIONS |

by Paris S. Strom, Auburn University

Robert D. Strom, Arizona State University

Presented to the

American Association of Behavioral and Social Sciences Conference,

February 2004, Las Vegas, Nevada.

This article appeared in

The Educational Forum, Summer 2004, 68(4), 325-335

Abstract There are differing opinions about how to achieve the national

goal of “No Child Left Behind.” Concerns involve relevance

and fairness of tests students must pass, merits and drawbacks

of retention policies, access to tutoring, qualifications of teachers,

and sufficient funding. These issues may expand to include debate

about whether college and vocational training should become an

entitlement. Related factors are rising tuition rates, financial

aid, demographic changes, career planning, curriculum practicality,

and labor market forecasts. |

Discussions about public education often include opinions on how to

evaluate basic skills, whether all students should be required to meet

minimal standards for graduation, and whether social promotion is warranted.

School districts continue to search for ways to improve remediation

efforts, increase the amount of learning time in classes, and reduce

dropout rates. These issues may soon be joined by concerns about whether

higher education and vocational training should become an entitlement.

By identifying ahead of time the factors that seem most crucial, educators

can help shape the debate in which parents and students will act as

the main proponents.

Looking Ahead at Economic Considerations

The burden of funding higher education has been shifting for some time

from government sources to students. This trend is reflected by significant

tuition increases at public colleges and universities across the nation.

Parents of young children are frightened by predictions of what going

to college will cost when their children are old enough to attend. Commercials

on television suggest that families start to save money for college as

soon as a child is born. This advice is based on economic projections

that, when today’s infants are ready for higher education in 2022,

the total tuition covering four years at a state university may be $50,000

or more. The current average tuition over four years is $20,000 at public

institutions and as much as $120,000 at elite private universities (Arenson

1997; Trombley 2003).

The first state to offer a prepayment plan to residents was Michigan in

1986. The details of these programs vary by state but commonly lock in

future tuition at current rates so families will be protected from escalating

costs. This approach is referred to as a Guaranteed Education Tuition

(GET) plan. Assume that the parents of an infant pay $5,000 this year

for their child's future tuition as a college freshman. The couple submits

the same amount during each of the next three years for a total investment

of $20,000. The combined prepayments cover tuition costs, thereby avoiding

possibly overwhelming expenses without the plan in 2022. Parents of students

in elementary grades or middle school can also join but must pay a higher

amount because their child will start college sooner. Prepayments are

put into a government trust and invested with a guarantee to pay four

years of tuition at any of the public universities or colleges in the

state. If a student is unable to meet academic requirements for admission

or chooses to attend a school in another state, a refund will be provided

with some interest penalty.

One assumption of prepayment plans has been that interest rates and college

tuition would rise at a corresponding pace. However, lower interest rates

but higher tuition has been the rule in recent years. A national slowdown

in the economy after the tragedy of 9/11 caused legislatures in most states

to reduce the funding level they contribute to the operation of colleges

and universities. Institutions have responded by increasing tuition; even

with high rates, the tuition students pay accounts for usually only one-fourth

the total cost of their education. Some states have temporarily denied

further membership in prepayment plans; others are restructuring the plan

so parent contributions will be tied to growing tuition; and still others

have initiated deliberations over whether the legislature should assume

responsibility to meet whatever shortfalls occur between the amount parents

have paid and what tuition ultimately will cost when the child goes to

college. The National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators

Web site describes the plans in place for each state along with contact

information -- http://www.nasfaa.org/annual/pubs/csp0202.asp

Congress passed the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act in 2001. This legislation enlarged the tax advantage for families to set aside money for tuition and approved a more versatile strategy to augment the prepayment options. Known as the 529 College Savings Plans, these alternatives do not lock in rates of tuition nor do they offer other guarantees. Investments depend on market condition risks so profits may not cover all college costs. However, this option has no maximum annual amount for the contribution and compounds interest tax-free so it can grow more rapidly. There are appealing features at the time the money is taken out as well. So long as the funds are applied for education purposes, earnings on the investment remain tax-free. The money may also be used to attend universities elsewhere than in the sponsoring state. Forecasts suggest that more than $15 billion will be invested in prepayment plans or the 529 college savings plans by 2010. One downside of 529 plans is that management fees can be high and certain states do not offer tax deductions (Tergesen, 2003). The College Savings Plan Network, an affiliate of the National State Treasurers, maintains a Web site which describes the options available in every state at http://www.collegesavings.org (click the link ‘Guide to Understanding 529 plans’).

The Gender Gap

Before 1980 more men than women went to college. The assumption then

was that continued efforts to bring equity would result in as many female

students as males. The surprise was that, while enrollment rates for women

have risen steadily in the past decade, the number of men attending college

has declined. Consequently, men now represent 44% of undergraduates nationwide

with an expectation of further shrinkage by 2010 (Rowan 2002). Women earn

57% of bachelor degrees and 58% of masters’ degrees. The higher

proportion of degrees currently completed by women than men are spread

across ethnic groups to include Whites (58%), Blacks (63%), Hispanics

(61%), Asians (55%), and Native Americans (62%) (National Center for Education

Statistics 2002).

One possible explanation for the gender reversal in enrollment is that

men are more likely than women to seek employment in the high tech sector

where a degree is less often necessary and pay is greater. These jobs

represent only 9% of the labor force. Another speculation is that a larger

proportion of men, especially from low-income backgrounds, choose to go

directly from high school to a trade such as telephone repair, aircraft

mechanic, and related fields where the income is good after short-term

training. This means there is no need to delay marriage or assume the

financial debt usually associated with four or more years of college.

Whether efforts should be made to recruit more men for college and how

to proceed with such a task has yet to become a public concern (Conlin

2003; Fonda 2000).

Everyone Needs Job Training

The new economy has made prosperity more dependent on educational attainment.

Demands for highly skilled employees are expected to accelerate, and the

proportion of jobs that require training beyond high school continues

to rise. Some estimates are that 70% of jobs will require post-secondary

education (Carnevale 2002; Freeman 2003). However, this does not mean

that every student should go to college. Many adolescents and their parents

erroneously suppose the choice must be between college or settling for

a service-related job that offers a poor economic outlook. These perceptions

do not match current conditions or forecasts. Indeed, 43% of bachelor

degree graduates have jobs for which they are overqualified (Lee 2000).

It seems that expectations students have as to where a college degree

will take them are alarmingly naïve (Johnson and Duffett 2003).

Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of jobs that pay well but require different

skills and credentials remain unfilled. According to the United States

Department of Labor (2002), half of the new jobs created by 2010 will

be available to students who enroll in short-term to moderate length training

following high school. The situation is complicated by a general belief

that, because most high school students express the goal of attending

college, the guidance they need to choose their career can be postponed.

This conclusion fails to acknowledge that high schools also are obliged

to provide vocational guidance for students who are not planning to go

to college. For these individuals, career exploration must occur while

they are still in high school or it might not happen at all (Gordon 2000).

Relevance of Core Curriculum

The curriculum of American high schools is most helpful in support of

general reasoning abilities. However, the core curriculum seems a poor

match for current expectations of employers. Anthony Carnevale (1999;

2002), labor economist and Vice President for Education and Careers at

the Educational Testing Service, estimates that at most only 13% of workers

will ever need to use algebra on the job even though two-thirds of high

school students are led to believe that their occupational future depends

on performing well in algebra. Dennis Redovich (2000), Director of the

Center for Study of Jobs and Education, presents a related challenge to

the common practice of requiring all students to pass tests on mathematics

skills that are unnecessary for employment. His job projections through

2006 led Redovich to conclude that high stakes testing in mathematics

is a hoax that should be exposed and eliminated.

Support for high stakes testing as essential for all students appears

to be eroding, even in terms of taking the results of tests seriously.

Over half of the high school freshmen and sophomores who completed the

2003 New York Board of Regents mathematics examination failed. Officials

at the New York State Department of Education initially interpreted these

results to mean that test items were too difficult. Later, the scores

of students who failed were adjusted to reflect what they would have meant

on a previous version of the test administered one year earlier. Using

a revised scoring chart, 19% more of the failing 9th graders and 27% more

of the failing sophomores were then identified as having passed the examination

(New York State Department of Education, 2003).

Richard Freeman (2003) of the Harvard University Center for Economic Performance

offered a reminder of the disappointing consequences that can occur when

greater demands for certain skills are alleged than are actually needed.

In 1987 the National Science Foundation predicted that, by 2006, there

would be a shortage of 675,000 scientists. These ominous figures were

used to convince Congress that the anticipated scarcity had to be met

or the country would lose its competitive edge. The solution proposed

by Erich Bloch, Director of the National Science Foundation, was to increase

the agency’s budget and recruit greater numbers of students for

science. In 1992 Congressional hearings were convened again, this time

to focus on the glut of young scientists who were having trouble finding

jobs in fields where large-scale shortages had been forecast. Internal

documents from the agency were made public revealing that staff had identified

errors in the projections and made them known. However, the leaders chose

to ignore this evidence (Mervis 1992).

The skills students will actually need following graduation from high

school should be acknowledged by boards of education and used to make

changes in the required core curriculum (Ohanian 2003). In testimony before

the Select Committee on Education and Workforce of the United States Congress,

Frank Newman (2003) from the Brown University Futures Project recommended

that educators be urged to prepare students for key skills identified

by the Business-Higher Education Forum that are typically lacking among

new workers. These competencies include computer literacy, teamwork skills,

problem solving abilities, time management, adaptability, analytic thinking,

self-management, and global consciousness.

Finding a Career Path

High school counselors devote considerable time to college-bound students

and individuals who present discipline problems, or suffer from crises

such as drug abuse (Boesel and Fredland 1999; Wagner 2003). In most high

schools the ratio is one guidance counselor to 600 students. Therefore,

it should not be surprising that adolescents who prefer to learn about

vocational training continue to be ignored in the same way they were in

the past (Grevelle 1999; Lynch 2000). Families are bombarded by reports

on rising costs of college but rarely receive information about tuition

rates at vocational and technical schools. High schools should help parents

become aware of these tuition rates, length of courses at trade schools,

average salaries of graduates on completion of studies, and placement

service success by the institutions. For example, DeVry Institute of Technology

reported that 96% of graduates are employed in their chosen field within

twelve months after completing a program (Hodges 1999).

Guidance that centers exclusively on the college bound students without

equal consideration for those who are interested in vocational training

is occupational discrimination and should not be tolerated (Boesel and

Fredland 1999). This was the conclusion reached by the United States Congress

when it enacted legislation during 1998 to implement new reforms in support

of vocational/technical education including an identity change for these

programs. Tech Prep is the new term (Grevelle 1999; Lynch 2000). Students

and their parents can benefit from learning how expectations of employers

are changing and how emerging job opportunities should affect preparation

for the workplace.

In this connection, Otto (2001) examined the perceptions of adolescents

about parent influence on their career path. The sample of 350 high school

juniors were asked to identify persons they spoke with about occupational

plans. Mothers were identified by 81% of students, followed by peers (80%),

and fathers (62%). Mothers as the preferred source for guidance were reported

by both genders and across ethnic groups. Although a much greater proportion

of fathers were employed than mothers, students felt that their mothers

were better acquainted with their interests and abilities.

Adolescents may look to mothers for answers about careers but the mothers

are keenly aware of their own lack of knowledge in this realm. Studies

of 739 White, Black and Hispanic mothers of adolescents considered self-perceptions

of parenting assets and limitations (Strom, P., Van Marche, Beckert, Strom,

Strom, and Griswold 2003; Strom, R., Dohrmann, Strom, Griswold, Beckert,

Strom, Moore, and Nakagawa 2002). Mothers ranked “I need more information

about helping my child explore careers” as their second greatest

need out of 60 items. Career exploration should be included as a focus

for educational programs that serve parents of high school students.

Another way to acquaint students with career opportunities calling for

post high school training but not a college degree is to arrange interviews

with skilled trade workers. This strategy can provide information needed

to make decisions about specific occupations, required skills, and satisfactions

as well as limitations in the marketplace. Interaction with workers allows

students to express personal goals and get feedback on whether the perceptions

they have about careers match the reality as experienced by persons employed

in the field.

Entitlement and Demographic Implications

Should college and vocational training become an entitlement for students

graduating from high school? Middle school and high school teachers can

ignore this question by claiming that learning which occurs after their

own involvement should be the obligation of other educators. A more constructive

perspective is for schools to help parents of adolescents begin to think

about and structure the debate for which they will likely assume leadership.

Recognizing why this controversy is imminent can enable faculty of secondary

schools to choose the role that is best for them.

Saving money for college is a reasonable expectation for affluent families.

However, half of all students who graduated from high school in 2004 were

from low-income households. The cohort of young adults (ages 18 to 24)

is forecast to increase each year during this decade, culminating in the

largest high school graduating class in the nation’s history in

2009. These students are concentrated in the western and southern states

where poverty rates are greatest. Higher Hispanic birth rates means they

will account for two-thirds of population growth among 18-24 year olds

(Callen 2003; Gonzales 2001).

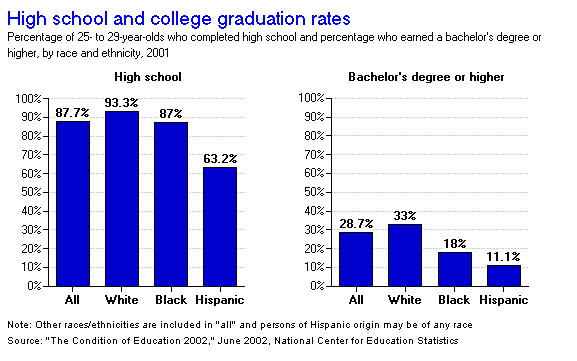

African Americans have nearly caught up with Whites in high school graduation

rates (see Figure 1). The comparative rates are 87% for Blacks, 93% for

Whites, and 63% for Hispanics (National Center for Education Statistics

2002). There must be other options for these students than just college

prepayment plans, 529 college savings options, tax shelters, income tax

deductions, or enlistment in the military to obtain veterans benefits

for attending college. Efforts to increase high school student graduation

rates should be joined by initiatives to ensure that college students

graduate in greater proportions as well. Figure 1 shows that the percentage

of 25- to 29-year-olds who have earned a bachelor’s degree or higher,

by race and ethnicity, is 33% among Whites, 18% for Blacks and 11% for

Hispanics.

Tuition Increases and Financial Aid

Tuition at public institutions has increased 80% in the past twenty years, twice the rate of increase in family earning power. If this trend continues, part time employment may not produce sufficient income for students working their way through college. Nearly 55% of college students work part-time or full-time, leading many of them to carry greater numbers of credits than can be well managed. The balancing act usually means too little time is spent on studying and consequently learning is compromised. This problem is widespread but usually more acute among low income and minority students (Immerwahr 2003).

Figure 1

Students generally take out loans and, on average, will owe $17,000 when they finish a bachelor’s degree (Monks 2001). Congress has approved increased tax credits and repayment options to partially offset the financial burden and allow students to pay back college loans over a longer timeframe (up to 25 years). Extending the period of payment substantially increases the amount of total interest. Some people will still be paying off school debts well into middle age while older students could be paying after retirement (Fossey 1998).

When student aid programs were introduced on a large scale during the

1970s, federal assistance was primarily intended for low-income students

to attend college. Since then, tuition rates have doubled causing lawmakers

to consider new ways for making college affordable for middle-class families

as well. For example, in 1997, President Clinton established a Hope Scholarship

Program offering $3000 in tax credits for two years of college. The goal

was to give college opportunities for a new generation. However, because

the poorest among families pay no federal income tax, they get no assistance

in this particular program. Instead, Hope tax credits are limited to those

students whose parents have annual incomes from $30,000 to $90,000 per

year, the group that would likely have made college available anyway.

There are notable exceptions like the state of Georgia where money generated

by the state lottery is set aside for college tuition of students who

graduate from high school with a B average (Callen 2003).

The result of financial aid packages and incentives favoring affluent

students is a growing gap in which applicants from the wealthiest quartile

are seven times more likely to get a degree than peers from low-income

households (Macy, 2000). This inequity will likely grow because the college

population is predicted to increase from 13 million students in 2003 to

21million by 2015. Unlike prior generations, 85% of this increase will

consist of minorities and 41% will be from low-income families. These

are the groups that generally have experienced difficulties going to college.

Looking ahead to the end of this decade, the Congressional Advisory Committee

on Student Financial Assistance estimated that lack of funds will prevent

4.4 million qualified high school graduates from entering a four-year

college and 2 million more from enrolling in a two-year community college

(Reed, 2004).

Support for and Opposition to Entitlement

More lengthy schooling is becoming the norm. To properly prepare for

a career, adolescents need greater learning than is provided by the elementary

and high school curriculum. If students cannot pay for the further education

they need to meet entry-level requirements of employers, the future is

bleak for them. This situation could adversely affect their financial

ability to support themselves and their families. The American concept

of equal educational opportunity is jeopardized unless post secondary

tuition costs are underwritten by society. This reform will be supported

as reasonable by a significant segment of the public and opposed by a

large population as well.

Many economists view the growing income gap between poor and affluent

as the greatest social problem and agree that equal access to higher education

could be the best solution (Bernstein 1999; McPherson and Shapiro 1997).

There is a range of imagined outcomes that could occur if higher education

were to become an entitlement. For students who come from low income families,

this unprecedented reform may create a broader sense of hope, perhaps

increase motivation to learn, improve attention in class and levels of

achievement, reduce the rate of disruptive behavior, diminish the appeal

of gangs, and implement the opportunity for equity our nation has promised

itself. Middle-income families would not have to set aside money for many

years to cover expenses of higher education. In turn, this would reduce

parents’ need to borrow and instead allow them to save for their

retirement. Students could spend less time employed and devote greater

attention to study. This would help them gain the skills needed for their

occupation, enter the work force sooner and without debt, and avoid the

anxiety associated with subjecting parents to financial sacrifice.

Those who oppose making higher education an entitlement could argue that

the nation should retain its tradition of fully funding only the amount

of schooling that is compulsory. Others may contend that students are

better off when they have to pay for the tuition because this causes them

to value their learning more and to study harder. Some critics may want

to attach conditions before policy change is approved. For example, they

may insist on ending the practice of offering remedial courses in college

so persons who have not fully qualified themselves will have to meet entry

standards before being allowed to participate in any tuition free program.

Some may seek assurances that will prevent state support of persons who

want to be perpetual students by placing limits on the number of times

a student can change majors or pursue studies in areas where the employment

opportunities are negligible.

Other restrictions could call for making the college curriculum more job

related and practical, improving the competence of graduates by increasing

the number of hours that must be taken to represent a major, and abandoning

the practice of requiring a year of general studies before being allowed

to study in a chosen field. Still another condition might be that universities

would be directed to increase guidance and monitoring by the faculty since

studies have consistently shown that nearly half of college freshmen fail

to complete a degree in six years (National Center for Education Statistics

2002).

Conclusion

The main concern of parents is no longer whether their children are able

to qualify for higher education but how the family will pay for college

expenses. Tuition-free education would include vocational training as

well as college. Until now there was no compelling reason for parents

of minor age children to organize themselves as a political lobbying group.

The assumption has been that communities would always assign high priority

to ensuring that children are well prepared to enter the world of work.

The failure of school bond issues during recent years has caused a growing

number of parents to conclude that they may have to mobilize to protect

the future of their children (Hewlett and West 1998).

A unified effort by parents would be necessary to override the objections

of special interest groups likely to assert that the nation is unable

to afford additional entitlements. However, Social Security and Medicare

on which a growing number of older adults depend cannot be financially

sustained unless younger people have the education they need to perform

well in a globally competitive workplace. No one can be sure when the

proposed debate will begin on a national scale but we believe the time

is soon. In the meanwhile, consider these questions: What are the pros

and cons of providing high school graduates with an entitlement to pursue

vocational training or a college education? What will be the outcomes

of public dialogue on this fundamental reform? When will the disparities

of access to higher education be recognized as sufficiently serious to

warrant beginning the debate?

References

Arenson, K. 1997, August 31. Why college isn't for everyone.

The New York Times, E1, 10.

Bernstein, A. 1999, May 31. What can k.o. inequality? College. Business

Week, 68-74.

Boesel, D. and E. Fredland. 1999. College for all? Is there too much emphasis

on getting a four year college degree? Washington, DC: United States Department

of Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement, National

Library of Education.

Callen, P. 2003. A different kind of recession. National Crosstalk. San

Jose, CA: National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, 2A.

Available at: http://www.highereducation.org/reports/affordability_supplement/index.shtml

Carnevale, A. 1999 October. Wanted: Strong thinkers. Scientific American,

89.

Carnevale, A. 2002. Education, training and the American labor movement.

Presented at the Annual

Conference on Working for America, 22 April, Philadelphia.

Conlin, M. 2003 May 26. The new gender gap. Business Week, 75-84.

Fonda, D. 2000, December. The male minority. Time, 58-60.

Fossey, R. 1998. Condemning students to debt: Is the college loan program

out of control? Phi Delta Kappan, 80(4), 319-321.

Freeman, R. 2003. The world of work in the new millennium. In What the

future holds: Insights from social science, eds. R. Cooper and R. Layard,

152-178. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Gonzales, V. 2001 May. Immigration: Education’s story past, present

and future. The College Board Journal, 193, 24-31.

Gordon, E. 2000, July/August. Help wanted: Creating tomorrow’s workforce.

The Futurist, 48-52.

Grevelle, J. 1999, April. The next generation of tech prep. The High School

Magazine, 6(6), 32-33.

Hewlett, S., and C. West. 1998. The war against parents. Boston: Houghton

Mifflin.

Hodges, J. 1999 June 7. If education is supposed to be an investment.

Fortune, 240-241.

Immerwahr, J. 2003. With diploma in hand: Hispanic high school seniors

talk about their future. San Jose, CA: National Center for Public Policy

and Higher Education.

Johnson, J. and A. Duffett. 2003. Where we are now. New York: Public Agenda.

Lee, L. 2000. Success without college. New York: Doubleday.

Lynch, R. 2000. High school career and technical education for the first

decade of the 21st century. Journal of Vocational Education Research,

25(2), 155-198.

Macy, B. 2000 August. Encouraging the dream: Lessons learned from first

generation college students. The College Board Review, 191, 36-40.

McPherson, M., and M. Shapiro. 1997. Student aid game: Meeting need and

rewarding talent in American higher education. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press.

Mervis, J. 1992, April 16. NSF Falls short on shortage. Nature, 356(6370),

553.

Monks, J. 2001. Loan burdens and economic outcomes. Economics of Education

Review, 20(6), 545-550.

National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators. 2004. State

Plan Summary Chart. Washington, DC: The Association. Available at http://www.nasfaa.org/annual/pubs/csp0202.asp

National Center for Education Statistics. 2002. The conditions of education.

Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. Retrieved November 2, 2003

from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/

Newman, F. 2003 May 13. Higher education in the age of accountability.

Washington, DC: Testimony before the Committee on Education and Workforce,

U.S. Congress.

New York State Education Department, Office of Communications, 2003 August

29. New scoring chart issued for Regents Math A exam. New York: State

Education Department.

Ohanion, S. 2003. Capitalism, calculus, and conscience. Phi Delta Kappan,

84 (10), 736-747.

Otto, L. 2001. Youth perspectives on parental career choice. Journal of

Career Development, 27(2), 111-118.

Redovich, D. 2000. What is the rationale for requiring higher math for

“all”? Greendale, WI: Center for the Study of Jobs and Education

in Wisconsin. Available at: http://www.jobseducationwis.org

Reed, A. 2004. Majoring in debt. The Progressive, 68(1), 1-4.

Rowan, M. 2002. The gender gap. The College Board Review, 197, 36-43.

Strom, P., D. Van Marche, T. Beckert, R. Strom, S. Strom, and D. Griswold.

2003. Success of Caucasian mothers in guiding adolescents. Adolescence,

38 (151), 501-518.

Strom, R., J. Dohrmann, P. Strom, D. Griswold, T. Beckert, S. Strom, E.

Moore, and K. Nakagawa. 2002. African American mothers of early adolescents:

Perceptions of two generations. Youth & Society, 33(3): 394-417.

Tergesen, A. 2003 September 1. Time to rethink the 529. Business Week,

92-93.

Toney, M., and A. Lowe. 2001. Average minority students: A viable recruitment

tool. The Journal of College Admission, 171: 10-15.

Trombley, W. 2003. Rising price of higher education. National Crosstalk

(supplement), San Jose, CA: National Center Public Policy & Higher

Education: 1-12. Retrieved November 2, 2003 from http://www.highereducation.org/reports/affordabilitysupplement/index.shtml

United States Department of Labor. 2002. Fastest growing occupations covered

in 2002-2003 Occupational Handbook for 2000-2010. Washington, DC: The

Department.

Wagner, W. 2003. Counseling, psychology and children. Upper Saddle River,

NJ: Prentice-Hall.

*Copyright © 2004 by Paris Strom and Robert Strom

For permission to use a whole or parts of this paper, write to bob.strom@asu.edu or stromps@auburn.edu