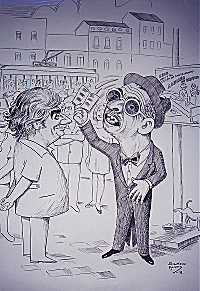

CORDEL:

ITS VALUE FOR “OTHER” BRAZILIANS

For

the poets and their readers cordel is entertainment, news and a moral

guide. The rest of the Brazilians

and interested foreigners may share such purposes with the humble cordelian

public, but probably for the former, cordel has other values.For Brazil

in general it represents the best written document of the traditions of the

humble class (but shared often by all classes) of the Northeast.

It is a part of the national cultural heritage.

For

the poets and their readers cordel is entertainment, news and a moral

guide. The rest of the Brazilians

and interested foreigners may share such purposes with the humble cordelian

public, but probably for the former, cordel has other values.For Brazil

in general it represents the best written document of the traditions of the

humble class (but shared often by all classes) of the Northeast.

It is a part of the national cultural heritage.

Sophisticated artists of Brazil’s elite

have borrowed, recreated and sometimes plagiarized the popular poets for

inspiration in works they want to be identified as “truly Brazilian.”

With the tenets of Modernism dating from the 1920s in Rio de Janeiro and

São Paulo, elite writers and artists wanted to create an art essentially

Brazilian rather than European oriented, so many used cordel as well as

other aspects of folk culture in their works.

Mário de Andrade admired cordelian poetry and used folklore in his Macunaíma

and “O Romanceiro de Lampião.” Jorge

de Lima used northeastern folk themes in his verse.

The writers inspired by Gilberto Freyre’s Regionalist Movement of the

Northeast in 1926 used both the poetry and the personage of the poets in their

works. José Américo de Almeida in

A Bagaceira, José Lins do Rego in Cangaceiros and Fogo Morto,

Raquel de Queiróz in many of her works, and Graciliano Ramos used the essence

of the difficult life of the vaqueiro to create Vidas Secas.

But of that generation Jorge Amado most of all used the poetry,

personages and values from cordel in many of his novels: Jubiabá,

Pastores da Noite, Tenda dos Milagres, especially Teresa

Batista Cansada de Guerra. In more recent times João Guimarães Rosa utilized the

sub-stratum culture shared by both Northeastern cordel and the folk

culture of Minas Gerais and Southern Bahia to create his masterpiece Grande

Sertão: Veredas. Ariano

Suassuna based a life of work on Northeastern folklore and verse, especially his play the Auto da Compadecida and novel Romance da

Pedra do Reino. And finally, João

Cabral de Melo Neto was deeply inspired by poetry and values in cordel or

the cantador in his wonderful Morte e Vida Severina.

There are many cinematic and televised recreations of the bandits of the

Northeast and of “religious fanaticism” in the stories of Antônio

Conselheiro, Padre Cícero or even Frei Damião.

Glauber Rocha of “New Cinema” fame was especially aware of the

tradition and used it in many of his films, including Deus e o Diabo na Terra

do Sol and Antônio das Mortes.

Northeastern pop singer Elba Ramalho also used verse from the cantadores

as inspiration for “Nordestinadas.” Luís

Gonzaga, O Rei do Baião, although not directly related to cordel,

shared many of its themes. The myth

of the northeastern migrant who flees the drought, but longs to return with the

next rains became the Northeast anthem in Gonzaga’s Asa Branca.

And in a different but ingenious way, Chico Buarque de Holanda retold the

myth in “Pedro Pedreiro.”

Samico and Brennand also borrowed from the popular tradition in their

painting and woodcuts. The famous

clay dolls [boneca de barro] of Caruaru and other fairs in the Northeast

share the same themes as cordel in their depiction of life in the region,

relying heavily on Father Cícero, Lampião, and the northeastern cowboy.

These are the “old-timers.” An

entirely new generation of artists continues to blend northeastern themes,

borrowings from cordel and recreation of the same today.