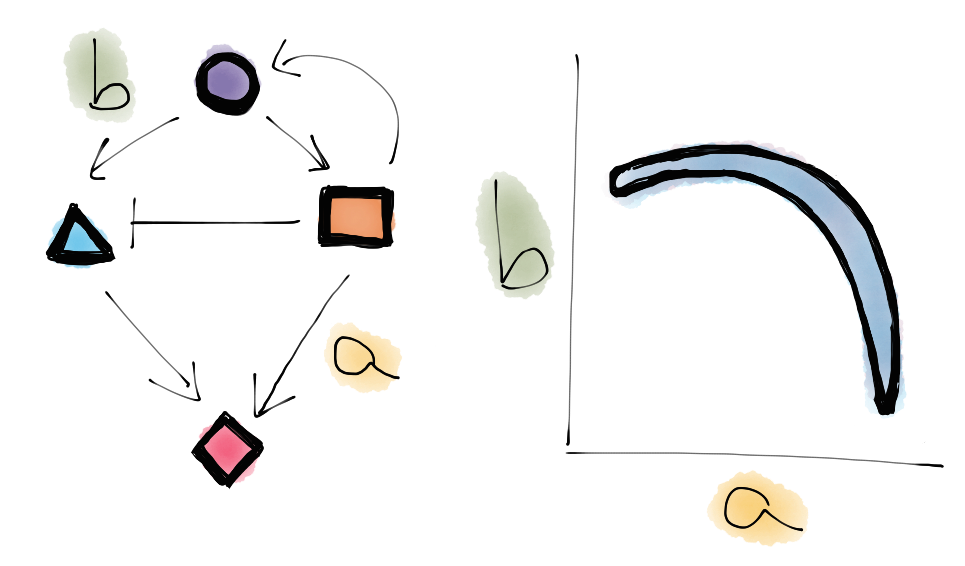

The biochemistry happening inside each one of your cells is amazingly complex. As an important example, take gene regulation. In the process of transcription and translation, proteins are constructed from the information in your DNA's genetic code. This process is regulated so that the cell can make more or less of a certain protein when it needs to (responding to, for example, the presence of a hormone in the bloodstream). The problem becomes more complicated when you realize that some proteins themselves regulate the creation of other proteins; we could find that protein A upregulates the creation of protein B, which downregulates the creation of protein C, and so on. In fact, huge networks of interacting genes and proteins are routinely studied in systems biology.

Understanding these large biochemical networks is a big challenge. For one, it's hard for experimentalists to measure what's going on inside a tiny living cell. Still, they can (painstakingly) discover which proteins are connected to which others (If I don't let the cell make protein A, do I still see protein B?), and a network 'topology' is gradually built up.

But what if we actually want to predict how much of a certain protein will be made under certain conditions (say, the addition of a drug)? Then we have to know not only the network topology (protein A upregulates the production of protein B), but specific numbers for each connection (protein A increases the rate of creation of protein B by 2.5x), and specific numbers for the rates involved (one copy of protein A is created every 5 seconds). If we're trying to model the network, we need to set numbers for lots of these parameters.

But these parameters are even harder to measure than the topology: Asking the question of how much protein is present is much more difficult than asking whether the protein is present. So we have to deal with limited information. We may only know the concentrations of two of the proteins in our network, and have only vague ideas about the concentrations of ten others. Then our group is tasked with finding values for 50 parameters that produce a reasonable fit to the available data, so that we can make a prediction about what will happen in other, unmeasured conditions.

As you might imagine, this problem is generally ill-constrained: there are lots of different ways you can set your parameters and still find model output that agrees with the available data. Some parameters could be intrinsically unimportant to what you measured. Some sets of parameters could compensate for each other; for example, raising one rate and lowering another might leave the output unchanged. (We say that there are lots of 'sloppy' directions in parameter space in which you can move without changing the model output.) And at first glance, it seems audacious to think that anything useful could come out of all of this. If we don't know our parameters very well, how can we hope to make valid predictions?

But it turns out that the situation is not so bleak. If we keep track of all of the parameter sets that work to fit the experimental data, we can plug them in and see what output each of them produces for an unmeasured condition. And we find that (well, Ryan Gutenkunst found that) oftentimes the outputs of all these possible parameter sets are alike enough that we can still make a prediction with some confidence. In fact, even if we imagined doing experiments to reasonably measure each of the individual parameters, we couldn't do much better. This is saying that the experimental data still constrain the predictions we care about, even if they don't constrain the parameter values.

There are lots of other interesting questions you can imagine asking about these 'sloppy models.' Can these models be systematically simplified to contain fewer parameters? Can other types of measurements (say, of fluctuations) better constrain parameter values? If organisms evolve by changing parameters, can 'sloppiness' help us understand evolution? You can learn more at my advisor's website: Sloppy Models.