A Message from Tommy Espinoza, RDF's President and CEO

RDF’s

mission has always been to serve the Hispanic and poor families alike

and as part of that, we invest in schools that have high academic

standards and educators that have the expertise and passion to educate

underserved children and enable them to reach their highest potential.

RDF provides financing to schools with innovative educational programs

that are managed by individuals with proven leadership

qualities. RDF’s

mission has always been to serve the Hispanic and poor families alike

and as part of that, we invest in schools that have high academic

standards and educators that have the expertise and passion to educate

underserved children and enable them to reach their highest potential.

RDF provides financing to schools with innovative educational programs

that are managed by individuals with proven leadership

qualities.

I was recently invited to

the University of Notre Dame to participate in a think-tank discussion

on forming a Catholic education leadership program. This gave me the

opportunity to listen and share ideas with businessmen, educators and

religious leaders from around the country on a subject dear to my heart,

education.

My experience at Notre

Dame was extremely rewarding and while various points of views were

discussed, a few major points of agreement were; the key role of the

principal and the leadership skills they should possess. These skills

include having a strong Catholic faith, managerial skills and most

importantly, a passion in educating children.

Discussions such as the

one at Notre Dame, are one of the many forums taking place and are

essential to the success of our children’s education because they

produce innovative ways of thinking, in regards to educating the next

generation.

In this issue of VOCES,

we look at different organizations and leaders who understand the

importance of innovative education. Finding unique and informative

resources have been increasingly important, as we move forward to a

digital and ever changing world of education.

We

look forward to receiving feedback from you, and we hope you will

share your comments and suggestions on our Facebook page, www.facebook.com/razadevelopmentfund

|

Innovation in Education: Why is it Needed and Will it Work?

By Paul Brinkley-Rogers

The

need for a quality education is acute, the road is long and hard, and

millions of young Latinos are searching for directions so that they can

earn degrees and find good jobs.

The statistics are grim.

The dropout rate for Hispanics age 16-19 is more than 21%, the highest

of all ethnic groups, according to the Pew Hispanic Center. A quarter of

Mexican immigrant children do not finish high school while 41% of adult

Hispanics over 20 do not have a high school diploma, compared with 23%

of blacks and 14% of whites.

But there is hope.

Innovation is happening in education. What is it? Will it help children

learn? Will hiring great teachers result in good grades? Will these

ideas help a new generation of Latino youngsters reach their full

potential in multicultural America, and in an increasingly competitive

world?

In this issue, Voces interviewed educators pioneering these changes.

We talked to two young

Hispanics who, despite poverty, used determination to earn degrees and

distinction in the workplace.

Latinos working for

American Honda and Intel, discussed how their organizations make

education and career opportunities available.

Latinas discussed the need for more women to become scientists and engineers.

Voces also looked at schools which have gone beyond

bilingual education by also offering Mandarin Chinese. A Phoenix

pre-school teaching 1-5 year olds in Chinese, Spanish and English, plans

to add Arabic. Latino parents with children in these schools said they

believe kids fluent in key languages will be highly employable.

Often, it takes a

visionary leader to make innovation happen. The leader maps out the

idea. Excited board members lend support. The idea energizes teachers to

make a difference. Parents compete to get their children into that

school.

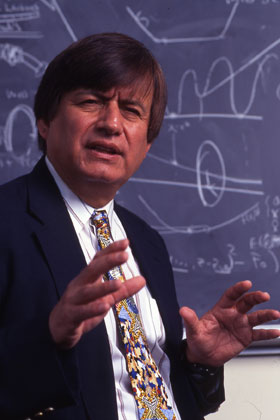

Richard Tapia, a

mathematician who is director of the Center for Excellent and Equity in

Education at Rice University in Houston, says that the need for fresh

ideas and directions is so intense he gets at least one invitation per

day to speak at public forums.

Tapia

says until Hispanics graduate from university in large numbers and are

prominent in the sciences and other demanding fields, they will not

occupy key power positions. “It is clear,” he said, “when you look at

where American leaders come from that if we are not where people are

going to be picked, we are not going to lead.” Tapia

says until Hispanics graduate from university in large numbers and are

prominent in the sciences and other demanding fields, they will not

occupy key power positions. “It is clear,” he said, “when you look at

where American leaders come from that if we are not where people are

going to be picked, we are not going to lead.”

Prejudice, Tapia said, is

not holding Latinos back: the issue is a lack of graduate degrees and

training affecting people from all ethnic groups.

Wendy Kopp, CEO of Teach

for America which has prepared 20,000 educators to work in underserved

communities, says that TFA’s work shows that lack of educational

opportunity robs kids of success, not socio-economic background.

“We live in a country

that aspires so admirably to be a place of equal opportunity and yet

somehow we have the reality that 13 million kids who grow up below the

poverty line, are by fourth grade already three grade levels behind on

average,” she said in a recent interview. Half will not graduate from

high school. Those who do will have eighth grade skills compared with

kids in high income areas. Only 1 in 10 will earn a college

degree.

Robert Carreon in

McAllen, TX, runs a TFA corps of 130 teachers working in 12 school

districts. There are 400,000 students in the Rio Grande Valley. 80% come

from homes where mostly Spanish is spoken. One in three have “limited

English proficiency,” according to the Texas Department of Education.

Before TFA arrived in

2003, Carreon said, teaching was done in English. TFA designed a

bilingual program designed to graduate students fluent in English and

Spanish who will use those languages in college. Command of two

languages is a plus in job hiring, he said. A second part of this

innovation trains students to be leaders.

Judith Camacho, executive

director of the Society for the Advancement of Chicanos and Native

Americans in Science (SACNAS), said that career opportunities are

virtually unlimited for young people graduating with STEM (Science,

Technology, Engineering and Math) degrees.

“Science and education

are the next civil rights struggle, especially for Latinos. When we look

at the number of jobs opening up and the need for science literacy, you

can see why this is so important. (President) Obama says that science

skills push innovation and right now we are beginning to lag behind

because we don’t have those skills.”

If parents knew, she

said, that babies in the crib are innovators, maybe they would point

their children toward a STEM education. “Science experiments begin as a

natural phenomenon in children as young as 3 months. A child discovers

that ‘If I cry, you will feed me. If I throw food, I am testing

gravity.’ It is social development, but it is also scientific

curiosity.”

Alexandra Warnier,

manager of the American Honda Foundation, says it has focused on

encouraging STEM education for the last 25 years. Eighty three percent

of the Foundation’s giving has been to minority children, and there is a

specific program – the Hispanic Youth Symposium Institute in Los

Angeles – dedicated to educating Latinos and, if possible, hiring them.

Jesus Chavez, 32, works

at Honda in Torrance, CA, as a stylist designing the outer skins of

Honda vehicles. His family emigrated from Michoacan, Mexico. He grew up

in a rough Los Angeles neighborhood.

How

did he earn a mechanical engineering degree from Cal State Northridge,

despite the odds? He took out loans. He tutored kids in math. He worked

construction. He engineered his own future. How

did he earn a mechanical engineering degree from Cal State Northridge,

despite the odds? He took out loans. He tutored kids in math. He worked

construction. He engineered his own future.

“My uncle took me to

Universal Studios to see the Knight Rider set when I was 10 years old,”

he said. “I spent most of my time as a teenager drawing cars. I wanted

to seek that path. I wouldn’t settle for anything else.”

In 2007, he went to a job

fair, applied at American Honda. He was soon hired. It amazed him, he

said, that he had won what he wanted.

“If I had words of

advice,” Chavez said, “it would be, never stop dreaming. No matter what

the hardship, you can do it. You’ll finally get there.”

The need for innovation and improving the future of young Latinos is also apparent to the Raza Development Fund.

Mark Van Brunt, RDF’s

Chief Operating Officer, said that lending for education has been

expanded to include parochial schools, and all schools public and

private, as long as they are not performing below district standards.

The Fund has provided financial support to more than 100 charter schools

in the last 10 years.

A contract has been

signed, he said, with the Saint Anthony School in Milwaukee, where 99%

of the 1,500 students are Latino, and 50% of those are first generation

immigrants. Another contract, with Saint Joseph’s High School in South

Bend, Indiana, using new market tax credits (NMTC), will finance

construction with the understanding that the school will send at least

200 students to Notre Dame University in the next decade. Both contracts

call for regular review by RDF of school performance.

In

addition, Van Brunt said, RDF is creating a Latino school leadership

fellowship program which will send aspiring educators to the finest

universities for training. Good leaders mean better opportunities for

school children. “To lose a child and the opportunity to advance often

sets that child back several grades for the rest of that child’s school

career,” he said.

Paul Brinkley-Rogers is a former reporter for Newsweek, The Miami Herald, The Arizona Republic, and the Phoenix-based Spanish language newspaper La Voz. He was a member of The Miami Herald’s reporting

team that earned a Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the highly emotional

child custody dispute in 2001 over Elian Gonzalez, the little boy who

survived the sinking of the boat bringing him and his mother from Cuba

to seek a new life in the United States. Paul won the Overseas Press

Club’s Malcolm Forbes award in 2002 for writing about the economic and

political turmoil in Argentina.

|

|

I Am the American Dream: Erika Tatiana Camacho PhD

Sometimes innovation

comes in the form of one person, in this case a young woman of Mexican

immigrant parents in East Los Angeles who once sold clothes in the back

alleys and against all odds, became a professor of mathematics at

Arizona State University.

Fierce

determination and will power enabled Erika Tatiana Camacho, 36, to

accomplish what is still the extraordinary for a Latina which is, a

cherished and coveted career at the highest level in the sciences. Fierce

determination and will power enabled Erika Tatiana Camacho, 36, to

accomplish what is still the extraordinary for a Latina which is, a

cherished and coveted career at the highest level in the sciences.

She innovated. Her family

did not have a computer so she wrote her application to prestigious

Wellesley College in longhand. “I said, ‘I am very sorry. I know the

instructions said to type (the application).’ At the interview, they

told me the letter tugged at their heart.

“When I was at Garfield

High School,” Camacho said, “I did not know how poor I was. I had holes

in my shoes.” When she arrived at Wellesley, an East Coast school for

women from wealthy families, she quickly discovered that she had come

from poverty.

Everything was stacked against her, she said.

But the fact that she

went on to Cornell University to earn her doctorate degree, shows that

despite the racial prejudice she encountered, despite the gender

prejudice, despite the jeers and teasing because she was a Latina who

dared to excel in a field dominated by Anglo males, it is possible to

wage a personal battle and succeed.

“I am the American dream,” Camacho said in a voice that was a mix of pride and humility.

The story of what she had

to overcome, and her desire for other Latinas to do the same “is a very

passionate topic for me,” she said. “I was born n Mexico (Guadalajara).

My mom was a house cleaner. She read a lot and was good at numbers. My

stepdad was a janitor. I started working when I was 13 years old. I

worked from 8 to 8 in the streets of Los Angeles.

“My wish was to become a

cashier – that was more than my parents did. I was good with numbers. I

didn’t know English, but math was a common language. I was tired of

being poor.”

She was fortunate that the extraordinary math teacher Jaime Escalante was her mentor at Garfield High (http://garfieldhs.org/). Escalante’s efforts to show that inner-city kids could master calculus, was portrayed in the 1988 film Stand and Deliver with

Edward James Olmos in the title role. Escalante, who passed away in

2010, saw Camacho’s talent and told her she was a perfect pick for

Wellesley (http://web.wellesley.edu/web).

Other people, however,

told her she should try something different. She wondered about

engineering. “I got into heated arguments that girls are not smart

enough, that they should not go into that field. I was told don’t go

into engineering. It’s not for you. We (Latinas) see engineering as a

white guy profession, a nerdy thing.”

But all that opposition,

often from friends and family, “made me want to show I have what it

takes. All of us (Latinas) can be engineers. It takes hard work to do

it.” Good grades meant that Camacho won fellowships. Her first employers

paid off her student loans.

She also had to deal with

lukewarm support, and hostility, even at Wellesley for her selection of

mathematics as a major. “I got an A- in two math classes. My mentor

there said ‘You are not PhD material. Be happy with your BA and teach.’”

A professor would not write a letter of recommendation for her to go to

graduate school, even though MIT invited her to deliver a lecture.

“Many times I called

Jaime Escalante to tell him about these experiences,” she said. At one

point she was treated by an Anglo nurse who claimed angrily that Camacho

had used her ethnicity to “steal” a slot at Wellesley. “Because

of people like you, my daughter did not get into Wellesley,” her accuser

declared.

Camacho said even as a professor, she still has to deal with what she calls “the impostor syndrome.”

“I still have to prove

myself because I have brown skin and I am a woman. I have to work twice

as hard to be accepted.” In her profession, she said, too often she is

viewed as “the Latina who is not really cut out to be a mathematician.”

Camacho said she

understands now that “If you grow up in an environment in which you are

told you are not good enough, that will become a self-fulfilling

prophecy.”

She is a frequent speaker

at conferences where there are workshops urging young women, and their

parents, to be interested in science and technology. The U.S. National

Security Agency has given her an award issued for guiding undergraduates

in research. She started a summer program at Loyal Marymount University

in Los Angeles for 16 students showing a potential to study in the

sciences.

When she is not teaching

as an assistant professor of mathematics at the New College of

Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at Arizona State University, she is

doing research in the interface of mathematical applications to biology

and sociology including transcription networks in yeast, interactions of

photoreceptors and fungal resistance under selective pressure.

|

|

Beyond Bilingual: Learning Mandarin Chinese

There is something energized and determined about parents whose children attend Starr King Elementary School in San Francisco.

“Why just be bilingual?

Learn three languages,” says Michaelia Szarnicki, whose half Cuban, half

Ethiopian children are experiencing five hours a day of Mandarin

Chinese immersion, which includes math and other classes taught in

Chinese.

“I asked myself, what

will the world be like 20 years from now,” she said. “I saw Asian kids

hitting the top of the mark in education and I decided that the future

will be Chinese and my four children will be ready for it. They will be

trilingual.”

Five years ago, Star King (www.starrkingschool.net)

was on the verge of closing because of declining enrollment. But after

Mandarin was first introduced in kindergarten in 2005, parents competed

to get their children into the school. Enrollment more than doubled from

151 students to 386 today. Two thirds of the students are in Mandarin

immersion, and Latino children are 10% of the total, said Principal Greg

John.

Ten full time Chinese

teachers are on staff, John said. Hiring is sometimes a challenge, but

video conferencing and Skype enable interviews with candidates in

mainland China and Taiwan. He wants the best. “Kids going into immersion

are living at a time so powerfully different from the age I grew up

in,” said John, who is 57. “To develop their minds and be successful in

the job market, kids need this.”

Twenty-one San Francisco

elementary schools have similar programs. Plans are being made to bring

Chinese immersion to middle schools, and then to high schools, so that

those who start in kindergarten develop real fluency.

Szarnicki is so committed

to the work her children are doing that she has hired a woman tutor to

come from China to live in her home. More and more Hispanic children are

participating, as parents see grades soar and children gaining fluency.

“I want to get the message out to Latino and African American parents,”

Szarnicki said. “Their children can do this.”

Another Starr King

parent, Maria Esquivel, is a medical assistant who came to the USA from

Guatemala in 1986 when she was 11. Her husband, Nelson, is a tow truck

driver from Cuba who came to the United States in 1989 when he was 15.

Their daughter, Jade, a 5th grader, has been learning Chinese since kindergarten.

Esquivel

wants her child to experience several cultures. “Jade is 10 years

old,” she said. “Being able to speak three of the most powerful

languages in the world can only be a plus for anything you want or

decide to do with your life, not only in college or for a good job but

for traveling and just living life.”

Luz Esquivel, who is from

Morelia, Mexico, and who is a bakery cashier, is scouting Starr King

for her two sons. “I want a piece of that school for my

children.” She said. “Learning Chinese is difficult, but it makes

children smart. I have seen it with my own eyes. My neighbor’s kids –

Mexican like me - caused a sensation when they spoke Chinese” to waiters

at a Chinatown restaurant.

Another Mexican immigrant

parent, Jorge Baca, said he supervises his daughter Carmen, 5, who is

already practicing writing Chinese and hopes to attend a school near

Starr King.

“In this country I do

yard work,” he said. “My daughter will speak three languages and she can

be a doctor in several countries. She will be able to make that

choice.”

Parents in the Bay Area

whose children are taking Mandarin (Cantonese immersion also is offered

at three schools), are well organized in the Mandarin Immersion Parents

Council (http://miparentscouncil.org). Their website is a place where parents can exchange information and view videos filmed by proud moms and dads.

Elizabeth

Weise is Council President. Her husband is Chinese-American. Their

daughters Eleanor and Margaret are in 5 and 3 grades respectively at

Starr King. At the end of this year, 240 students in six grades – K-5 –

will be in Mandarin immersion, she said.

The rapid shift to

studying Chinese has changed the character of Starr King. The school is

in the lower income Potrero Hill district where many residents are

Latino or black.

Most students in Mandarin

immersion are Anglo or Asian, and there are also many mixed race

children, Weise said. “Most of the Latino children come from highly

educated bilingual families.” But there is an increasing number of

“working class immigrants without a college education who are starting

to understand that if ‘My kids can speak Spanish, English and Chinese, they can rule the world.’”

Some Latinos are not

happy with the sharp drop in children taking Spanish immersion. But on

the other hand, Mandarin “integrates schools” Weise said. “White parents

help raise funds. Their children raise the English ability of the

Spanish speaking kids.”

Carmen Cordovez, from

Quito, Ecuador, has a son, Sebastian, in kindergarten, and a daughter,

Isabella, in 3 grade. At home, she speaks only Spanish to her children.

Her American husband speaks English at home. Her kids are, in other

words, learning three languages at the same time.

Cordovez said it is clear

to her that at a very young age children learn languages quickly. She

said she and her husband are sharply focused on what their children are

accomplishing. “We live simply,” she said. “We are not super spenders.

We don’t have a big TV or a car. We want the best for them.”

“My daughter told me she

wants to learn Chinese. I said, ‘Mija…it’s too hard.’ She said, ‘Papi.

You came to this country. That was hard, but you did it. Let me do

this.’ When she said that, it made me proud” said Baca.

|

| Three Schools, Three Visions

The National Center for

Education Statistics says there are 98,800 public and 24,500 private

schools in the USA. There are 81.5 million students: 37.9 million

primary, 26.1 million secondary, and 17.5 million in college.

One in four

kindergartners are Latino. One fifth of K-12 students are Latino. The

numbers are growing fast. Student achievement remains troubling.

However, some schools

have imaginative programs with inspired leadership and teachers. The

curriculum and the homework are demanding. The children do well. Their

grades are high and parents with a passionate interest in their

children’s future seek out these schools. Often there are waiting lists.

Voces chose to look at two charter schools and one private school where the vision is strong.

The Equity Project (TEP)

is a publicly funded, privately run charter school in Manhattan with 15

teachers and 247 students in grades 5-8. It was started in 2009 by a

then 32-year-old Yale graduate named Zeke Vanderhoek on the theory that

excellent teachers are critical for success: not small class size,

talented principals or technology.

Great teachers, hired

from across the USA, have meant that grades are up. But not all great

teachers are prepared to teach school in trailers in an inner city

neighborhood where poverty exists. Retaining teachers remains an issue

even though the base salary, $125,000 per year, is twice that of New

York City public schools.

TEP (http://www.tepcharter.org),

which operates from a series of trailers painted red, is not going to

cut and run, however, Vanderhoek says. It (TEP) is only $3.5 million

short of a $28 million capital campaign to build a permanent facility.

The school has shown

success with student performance. But it is still an experiment in the

making, Vanderhoek says. Committed teachers are a great asset, but

poverty is a drag on student performance. “Are we where we want to be?

No. Are we on the road? Yes. We are still very much a start up in many

areas.”

TEP ranks in the top 1%

of New York area middle schools. It ranks especially high in safety and

respect. In areas of student proficiency TEP is still behind: 55% show

proficiency in math, up from 30% in the first year. Only 30% show

proficiency in English skills. Some 88% of students are Latino

immigrants, from the Dominican Republic and Mexico and the remainder are

African American.

TEP is using Latin and

music in an attempt to boost language development. Parents clearly love

what the school is doing. There is a long waiting list and openings for

students are decided by lottery.

Like TEP, Phoenix

Collegiate Academy (PCA), a back to basics charter school, is housed in

temporary space: a 22,000 square foot former bowling alley and thrift

store.

PCA (http://phxca.org)

had exceptional first year results in the 2010 AIMS exams given by the

state of Arizona. Some 69% of students passed in reading, 63% passed in

math – including 28% who exceeded standards, and 65% passed writing.

Latinos are 81% of the student body. The school was founded in 2009, and

is presently serving grades 5 through 9. It will grow one grade per

year until it adds 12 grade.

Akshai

J. Patel, managing director, said students “have to be willing to

develop the ability” like the school “to do innovative things.” Patel,

like Rachel Bennett, the school’s founder, is an alumnus of the inspired

education approach of Teach for America . Akshai

J. Patel, managing director, said students “have to be willing to

develop the ability” like the school “to do innovative things.” Patel,

like Rachel Bennett, the school’s founder, is an alumnus of the inspired

education approach of Teach for America .

After they left Teach for

America, Patel and Bennett spent some time studying successful schools

in other parts of the country. “Sure we wanted to attain state

standards,” he said, “but we wanted to go much higher.”

Students are looked at

closely to identify their strengths and weaknesses and teachers are

studied to see if they are “a mission fit.” Students are required to

take rigorous course work in a foreign language, math and science.

“Enrichment classes” are available in dance, origami and music.” There

are no text books. Instructional material is “teacher made.”

Patel said that school

staff still goes door-to-door to tell parents about PCA. “We knock on

doors in areas around us starting in spring,” he said. The school

encourages parents to become involved. Initial reactions from pupils is

often that the school is “too strict, too hard, and gives a lot of

homework.” Parents, accustomed to low performing schools in that part of

Phoenix, appreciate that, however.

BeBei Amigos Language School (http://www.beibeiamigos.com/)

is a private school in Phoenix serving children ages 1-5 in toddler and

preschool with Spanish and Mandarin Chinese language immersion

programs.

A

second school – Arizona Language Preparatory – has been added, and is

offering kindergarten. Plans are to add a grade each year through the

6th grade, enabling BeiBei graduates to continue to perfect Chinese and

Spanish. Co-founder Emily Sheen said that the school has applied for

charter school status, and it may soon add Arabic immersion so that when

English is factored in this will mean that children will be using four

languages. A

second school – Arizona Language Preparatory – has been added, and is

offering kindergarten. Plans are to add a grade each year through the

6th grade, enabling BeiBei graduates to continue to perfect Chinese and

Spanish. Co-founder Emily Sheen said that the school has applied for

charter school status, and it may soon add Arabic immersion so that when

English is factored in this will mean that children will be using four

languages.

There is strong evidence

that language training helps academic performance and in a child’s

intellectual development. In addition, said Sheen, who is from Taiwan,

children fluent in several languages will be true citizens of

globalization. They will be prepared for a future like no other American

kids.

“In a foreign country,

most students learn English,” she said. They grow up bilingual. But

American students typically do not enter their working years with

multilingual fluency. “We need to deal with what is going on in the

world,” she said.

Evidence that

BeiBei students are gaining fluency is apparent when a child asks for

something. “The child asks me in Chinese,” she said. “I say ‘No!’ He

goes to the next person and asks in Spanish. Then the next person, and

asks in English.”

Sheen said BeiBei was

founded by parents who were not happy with language opportunities in

regular schools. She is married to an engineer from Spain. Her children,

who are growing up speaking English, “need to communicate with their

grandparents who only speak Chinese or Spanish.”

Sheen has an engineering

MBA from the University of Texas. The other co-founder, Sean Diana, has a

MA in Education and is studying for a Phd at Arizona State University.

BeiBei has 39 students. The director, Denise Ramos, is from Sonora, Mexico. Four teachers are Latina, three are Chinese.

|

| Science: Careers in Technology for Latinas

One of the highlights of

the annual Hispanic Women’s Corporation (HWC) conference in Phoenix was a

presentation titled Inspiring STEM Leadership.

The outline for the

workshop read, “Girls lose interest in science and math at junior high

levels. Understand what you can do as a school administrator, teachers,

family and friends to make a difference in promoting Science,

Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) for our children. Career

opportunities will be presented.”

The key speakers were

Gabriela Gonzalez, the Intel Corporation’s University Programs Manager

in the Academic Programs and Research Office, and Professor Erika

Tatiana Camacho, a mathematics professor at Arizona State University

whose personal story is profiled this month separately in Voces.

Camacho reminded the 40

young women in the audience that although there are many STEM jobs

available, only 2% of those studying a STEM subject are Latinas. Latina

mathematics professors are as rare as diamonds, it seems.

Gonzalez, who has

master’s degree in manufacturing engineering, is a Phd candidate at

Arizona State focusing on young women studying the sciences. “If I look

at Hispanic girls our enrollment (in STEM) is growing, but it is flat.

Latinas are less than 1% of students graduating in engineering. I

enrolled in my field 20 years ago and for 20 years I have been involved

in community outreach – speaking to girls, mostly Latinas.”

She is especially

involved since 2005 in Hermanas: Diseña Tu Futuro (Sisters: Design Your

Future), an organization which has brought thousands of middle and high

school students to Stem presentations.

Gonzalez said there are

several reasons that Latinas are not involved in STEM. “Part of it is

because of socio-economic factors. Parents are a role model. Most

parents usually come to this country and engage in lower paying jobs.

Often, they themselves do not have a college education. These parents

are not likely to be in technology fields. They had to make money to

survive.

Parents may not have the

skills to help a child doing homework in a STEM field. “I see it in my

own family,” said Gonzalez, who emigrated to the US from Monterrey,

Mexico, when she was 13. “The value of an education takes second place

to athletics and entertainment.”

Sometimes in her

outreach, Gonzalez said, “When we ask a girl, ‘What is engineering?’ she

has no idea. You ask ‘What is a teacher, a doctor?’ and they have a

clearer idea. Most adults don’t know what engineers do. Culturally,

Latinas tend to stick to cultural roles.”

Here and there, some

organizations are trying to interest young women. Cecilia Hernandez of

the American Chemical Society in Washington DC, is an immigrant from

Cartagena, Colombia. She helps run the Society’s SEED Project which has

involved more than 10,000 students – a small portion of who are Latinas –

in summertime chemistry study.

Judith

Camacho, executive director of the Society for the Advancement of

Chicanos and Native Americans in Science (SACNAS) said that 55% of the

4,000 participants at the group’s annual meeting in November were women.

They appeared to be especially interested in biological sciences and

medical schools, but not in chemistry, physics or math. Judith

Camacho, executive director of the Society for the Advancement of

Chicanos and Native Americans in Science (SACNAS) said that 55% of the

4,000 participants at the group’s annual meeting in November were women.

They appeared to be especially interested in biological sciences and

medical schools, but not in chemistry, physics or math.

“In the past 20 years,”

she said, “it has been impossible to come across more than two Latinas

mathematicians in one year. Camacho is a mathematician herself. Lack of

interest in STEM she said is 40 years out of date. Parents and young

people should wake up to the fact that careers are available that cannot

be matched by any other profession. “We should be done with ‘As long as

you finish high school…”

Doris Roman, a Puerto

Rican educator and engineer living in Phoenix who for many years has

been working hard to connect Latinas with the sciences, said that

something needs to be done on a national level to raise the level of

interest, and willingness, to be a scientist or work in technology.

Maybe churches could be

involved, she said. Science should be part of the Hispanic community’s

culture. Community Colleges could organize to attract more women.

Politicians, community leaders, local organizations should spread the

word and increase awareness so that parents also become involved.

“Latinas are very

powerful, strong willed women culturally,” Roman said. “Talk about

‘Amazon women’ … hello! And if you give them a STEM education, watch out

world. We can do anything: find a cure for AIDS, invent a new

cellphone.”

|

|

IN THIS ISSUE...

- A Message from Tommy Espinoza, RDF's President and CEO

- Innovation in Education: Why is it Needed and Will it Work?

- I Am the American Dream: Erika Tatiana Camacho PhD.

- Beyond Bilingual: Learning Mandarin Chinese.

- Three Schools, Three Visions.

- Science: Careers in Technology for Latinas.

|

|

Community Corner

The

late Cesar Chavez had many great words of encouragement for people whom

he represented, and if you’re driving through south Phoenix on Central,

going toward the downtown area, off to the east you might be able to

catch a glimpse of a few of these empowering words on a mural at a local

school.

Fittingly,

the school, which is located in an underserved area of Phoenix, is

called Cesar Chavez Community School. Recently, a project that was

sponsored by State Farm® and Raza Development Fund was completed and

unveiled for the school’s Cesar Chavez Day celebration. Victor Mason, a

south Phoenix State Farm agent, attended the unveiling of the mural, and

for Mason it was yet another event he was able to attend in the

community that he invests so much time and effort in improving.

The

State Farm office where Mason works is only a few miles away from Cesar

Chavez Community School. Mason not only works in the area but said

south Phoenix is the community that he calls home. Mason said he’s

“embedded in the (south Phoenix) community” and it’s a community that he

spends a lot of time in with his children.

Prior

to the unveiling, Mason was able to meet the local artists working on

the mural when it was only about 40% complete. Mason said “anytime you

get to see something from the beginning it’s like ‘oh ok it’s coming’

but when you see it at 100% you realize how much energy and time was put

into it.”

One

thing that Mason mentioned, unique to the mural project at Cesar Chavez

Community School, was the fact that some of the students were able to

work alongside the artist in painting the mural. “To see that the kids

collaborated with the artists to create that (the mural) is the most

exciting piece of it all because those kids can all walk past that mural

five years from now or 20 years from now and say ‘I did that, I

impacted my community and put my stamp on it.’”

Due

to district budget cuts, Cesar Chavez Community School has not had the

means to have an art program for that past few years, and for local

artist Gennaro Garcia, the mural was a chance for him to give back to

the community by allowing some of the students to participate in the

painting process. This student-artist collaboration has not only served

as an art lesson but also as a way to instill pride for the community in

the students.

The

community surrounding the school is indeed classified as “underserved”

but in order for things to get better, it takes people who have

the pride for their community to stand up for it and make changes. These

children have been given this pride needed to make changes and for all

parties involved, this is the biggest return on investment anyone could

ask for.

Cesar

Chavez’ words on the mural read: “We cannot seek achievement for

ourselves and forget about progress and prosperity for our community …

our ambitions must be broad enough to include the aspirations and needs

of others, for their sakes and for our own.”

For

Mason and Garcia, their ambitions for themselves include bettering the

community and are achieved through their commitments to the people of

the community.

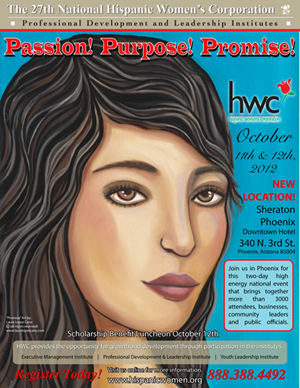

The

Hispanic Women's Corporation empowers Latinas and youth to achieve more

by serving as a voice for their community. The HWC's annual conference,

which takes place this year on October 11 and 12, is a gathering of

great minds where inspiring testimonials can be heard, for more info on

the conference please visit:

www.hispanicwomen.org.

|

|