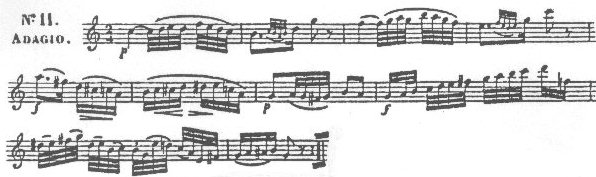

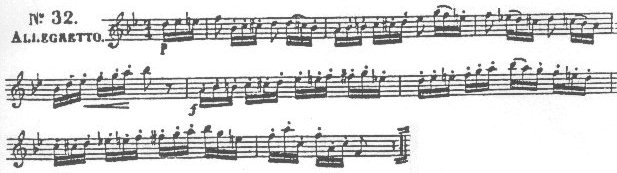

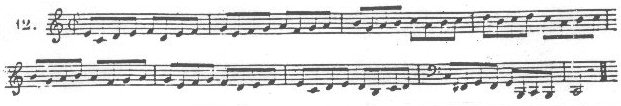

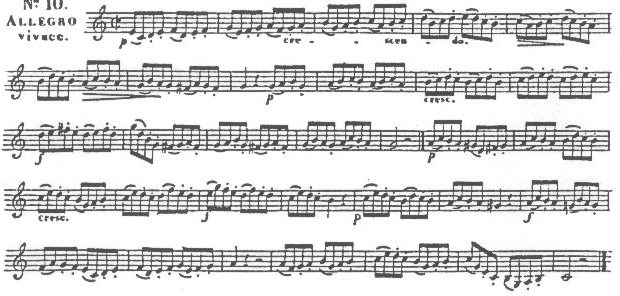

The Original Kopprasch EtudesGeorg Kopprasch and his music. John EricsonThis article is based on materials published in The Horn Call 27, No. 2 (February, 1997). The Kopprasch etudes. Practically every serious student of the horn today has studied these etudes, but who exactly was Kopprasch and when were his etudes first published? In spite of their popularity, until the recent research of Dr. Robert Merrill Culbertson, Jr. (completed in 1990) very little information was available about the original publication of these etudes or their composer. Of all the hornists that worked in Berlin during the period that Heinrich Stölzel (1777-1844) was there actively promoting his invention of the valve, one name stands out today: Georg Kopprasch. Kopprasch was the son of bassoonist and composer Wilhelm Kopprasch (ca. 1750-after 1832), who was a member of the orchestra of the Prince of Dessau [Culbertson, 2]. Georg Kopprasch first came to notice as a hornist in the band of the Prussian regiment, and was a member of the orchestra of the Royal Theater in Berlin in the 1820s. Kopprasch is listed as being second hornist in an 1824 roster [Pizka, 25]. By 1832 Kopprasch had returned to his family home of Dessau as second horn in the court orchestra, as is noted on the title page of the original edition of his etudes, where he likely spent the remainder of his career. A conservative estimate as to his dates would place Georg Kopprasch living from just before 1800 until sometime after 1833. Georg Kopprasch wrote and published a number of works for the horn. Belgian musicologist F. J. Fétis (1784-1871) in Biograhpie Universelle des Musiciens reported the following: We have of his compositions: 1) Six short and easy quartets for four horns, Leipzig, Kollmann. 2) Twelve short duos for two horns, Leipzig, Kollmann. 3) Three grand duos, idem., ibid. 4) Six sonatas for two horns, two trumpets and three trombones, Leipzig, Peters. 5) Sixty etudes for cor alto (premier cor), op. 5, ibid. 6) Sixty etudes for cor basse (second cor), ibid [trans. in Culbertson, 3-4]. The etudes for Cor basse, Op. 6, are particularly important; they have been studied by generations of brass players and are in widespread use today. The etudes were first published in 1832 or 33 by Breitkopf and Härtel in Leipzig [Culbertson, 47-48]. While it is not known if any specific event inspired Kopprasch to write these etudes, it is possible that they were written for use at the Musical Institute in Dessau, which had been founded in 1829 by Friedrich Schneider (1786-1853), Kapellmeister to the Duke of Dessau [Gehring, vol. 4, 269]. Notably, Schneider had written one of the first reviews of the valved horn earlier in his career from Leipzig. This review, which appeared in Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung in 1817, gives some insights into the musical world that Kopprasch worked in, and vividly explains how Schneider felt music would benefit from the valve. Because of its full and strong, yet soft and attractive tone, the Waldhorn is an extremely beautiful instrument; but, as is well known, it has until now been far behind almost all other wind instruments in its development, being very restricted to its natural notes .... Returning to Kopprasch, there are a total of 120 etudes; Op. 5 contains 60 etudes for Cor alto and Op. 6 contains 60 etudes for Cor basse. As Fétis noted, Kopprasch adopted the terms for the two types of horn from those advocated by Louis-Françios Dauprat (1787-1868) in his Méthode de Cor alto et Cor basse of 1824. Horn players of the time felt that the four octave range of the horn could not be mastered by one player, which resulted in specialization by range. Dauprat's comments on this subject are most relevant in considering the distinct division between high and low horn players at this time. Since the range of the horn encompasses four octaves ... it is not possible to cover its full extent without using two mouthpieces of different diameter. Therefore, as it is likewise impossible for one person to adjust from the one to the other, or to use them in alteration, it is really necessary to have two instruments, or at least, two players, one of whom covers the middle and high notes, the upper part, and who for this reason is called the first horn; the other, who covers the middle and low notes, the lower part, and is called the second horn. Thus, following this model, the differences in terms of range between the high and low horn etudes of Kopprasch are quite distinct. The Op. 5 etudes are for the Cor alto and cover a written range from b to f''', with a general tessitura in the range from written c' to c'''. These high horn etudes are especially virtuostic, but within the parameters of what was considered possible for the high horn players of the period. The work contains a mixture of technical and lyrical studies; the following are examples of both. Example 1. Kopprasch, Etudes, Op. 5, etude no. 11, mm. 1-10. Example 2. Kopprasch, Etudes, Op. 5, etude no. 32, mm. 1-8. UPDATE. Long out of print, the Op. 5 Kopprasch etudes are now available in a new, Urtext edition from Thompson Edition, with a foreword by John Ericson. The Op. 6 etudes for the Cor basse cover a written range from F-sharp to c''', with a general tessitura in a range from written c to a''. While this was within the normal range of the Cor basse of the period, the even distribution of pitches in the low range was quite new. Composers of low horn etudes before Kopprasch generally centered their low range pitches around the open tones of the natural horn, while Kopprasch wrote for a completely diatonic/chromatic low range. This is obvious right from the first etude. Example 3. Kopprasch, Etudes, Op. 6, etude no. 1, mm. 1-16. A number of the etudes in both volumes expanded on thematic ideas from exercises found in the methods of Dauprat and Heinrich Domnich (1767-1844) [Culbertson, 60]. The following examples show the common thematic materials and how Kopprasch transformed them into a cohesive binary form. (Kopprasch Op. 5, etude no. 8 is based on the same material as well. Culbertson gives other examples of transformations of this type in his dissertation on pages 63-66.) Example 4. Domnich, Méthode, p. 72, no. 61. Example 5. Dauprat, Méthode, pt. 2, p. 69, no. 12. Example 6. Kopprasch, Etudes, Op. 6, etude no. 10. Finally, Kopprasch used what is known today as "new" notation for the bass clef writing, as had Domnich in his Méthode de Premier et de Second Cor (1808). The following etude is an example of this. An accompanying footnote explained the notation. [NOTE: Only the edition by Oscar Franz maintains the original bass clef notation of Kopprasch. In Gumpert derived editions these notes are printed in "old" notation, and in the Schantl edition these bass clef notes are taken an octave higher, in treble clef. See the article Later Editions of the Kopprasch Etudes for more on these editions.] Example 7. Kopprasch, Etudes, Op. 6, etude no. 29, mm. 1-18. Kopprasch presents many technical challenges to the hornist through these etudes, especially in the approach to the extreme ranges of the instrument. While many of the Op. 5 etudes would certainly lie better in terms of range in a lower key, there are no indications to transpose or use a lower crook. In fact, there are no technical indications of any sort with regard to the use of crooks, fingerings, hand stopping, or transposition in any of the Kopprasch etudes as originally published. The complete lack of these markings raises a difficult question: did Kopprasch write these etudes for the valved horn or for the natural horn? The title pages give no clues, therefore we turn to the music itself. While the overall character of these etudes does not rule out natural horn writing on a virtuoso level, the approach to the low range shown in example 3 would point very strongly to the use of the valved horn. The central issue is the low horn writing. Since Kopprasch adopted the terms Cor alto and Cor basse from Dauprat, his Méthode is a very appropriate source which may be used in a comparison with Kopprasch's horn writing. In comparing the pitch content of large sections of both works containing the same general technical requirements, for example the Cor basse etudes found in Kopprasch, Op. 6, book I, and the Cor basse exercises found in the Dauprat Méthode, part 2, one finds the same overall gamut of pitches used rather differently. By making a chart of the frequency of the appearance of all the pitches one notices distinct clusters around the open tones of the natural horn in Dauprat, while in Kopprasch one finds a much more even distribution of pitches. While this could indicate nothing more than a difference of compositional styles (or even just bad natural horn writing on the part of Kopprasch), this even distribution of pitches does tend to lend even more support to the theory that these etudes were written for the valved horn. After examining the evidence in his study of Kopprasch's etudes, Culbertson concluded "It is quite plausible . . . that Kopprasch saw a developing need for studies which, while playable on the hand horn (with a good deal of difficulty, in some studies), gave the valve horn player a good workout as well" [Culbertson, 101-102]. This may well be the case. It is, however, equally possible that the etudes were actually written for the valved horn, and were published without this designation in order to avoid affecting the marketability of the publication among natural horn players. The low range writing in particular is very well suited to performance on the valved horn and extremely difficult and even uncharacteristic for the natural horn. Kopprasch certainly knew Heinrich Stölzel and other performers actively performing on the valved horn in Berlin. Additionally, hornist and composer Georg Abraham Schneider (1770-1839), the composer of one of the very first works for the valved horn, was Kapellmeister in the first years that Kopprasch performed in Berlin. [See the related article, The First Works for the Valved Horn.] These facts, combined with the already noted favorable attitude toward the valved horn of Dessau Kapellmeister Friedrich Schneider, points to the probability of these works being for the valved horn. Kopprasch was at the very least familiar with the valved horn and, as a second hornist himself, he could hardly have escaped noticing its advantages in the lower range. Unfortunately, there is not enough evidence to definitively state that Georg Kopprasch even played the valved horn. It is to be hoped that further research will shed light on this significant question. But whatever instrument he played, we can say for certain that his etudes opened new technical challenges for hornists, and that his etudes have secured for Kopprasch a certain immortal fame among brass players far beyond anything he could have ever dreamed. This article continues here with information on later editions of Kopprasch SOURCES Robert Merrill Culbertson, "The Kopprasch Etudes for Horn," D.M.A. treatise, University of Texas at Austin, 1990 [includes a complete reprint of the original Op. 5 and Op. 6 of Kopprasch]. Louis-François Dauprat, Method for Cor Alto and Cor Basse, trans. ed. Viola Roth (Bloomington: Birdalone Music, 1994), part 1, 6-7 [14-15]. Heinrich Domnich, Méthode de Premier et de Second Cor, French, German and English ed., English trans. Darryl G. Poulsen (Kirchheim: Hans Pizka Edition, 1985). F. J. Fétis, Biographie Universelle des Musiciens, 2nd ed. (Paris: 1874; reprint Bruxelles: Culture et Civilisation, 1963), vol. 5, 85. Franz Gehring, "Schneider, Johann Christian Friedrich," Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, J. A. Fuller Maitland, ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1909), vol. 4, 269. G. Kopprasch, Soixante Etudes, Op. 5, 2 vols (Leipsic: Breitkopf & Härtel, [1832/33]). ________, Soixante Etudes, Op. 6, 2 vols (Leipsic: Breitkopf & Härtel, [1832/33]). Hans Pizka, Hornisten Lexikon (Kirchheim: Hans Pizka Edition, 1986). Friedrich Schneider, "Wichtige Verbesserung des Waldhorns," Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 19 (November 26, 1817), col. 814-816, trans. in Kurt Janetzky and Bernhard Brüchle, The Horn, trans. James Chater (Portland, OR: Amadeus Press, 1988), 74-75. Copyright John Ericson. All rights reserved. |