FIFTH LECTURE

A profound shift begins to occur in science fiction by the early Sixties.

Without going into too much historical detail---most of which you probably

already know---America was in the process of becoming entangled in the

civil war in Vietnam. We had begun sending "advisors" (a euphemism

for the Green Berets) to assist the government of South Vietnam in 1958 after France had long abandoned its colony there

and by 1963, when Lyndon Johnson became president in the wake of John

F. Kennedy's assassination, we were up to our knees in the war and all

manner of domestic unrest at home. The Civil Rights movement was in

full swing and the environmental movement saw its beginnings during

this period as well (mostly because of what napalm and Agent Orange

did to the people who both dumped it and the people upon whom it was

dumped).

Meanwhile in the Soviet Union Brezhnev was in, Khrushchev was out. Cosmonauts and astronauts were setting their sights on the moon. The times were a changin', to quote Bob Dylan, and life at home and abroad was becoming a bit surreal. Science fiction, however, was a few steps ahead of the game.

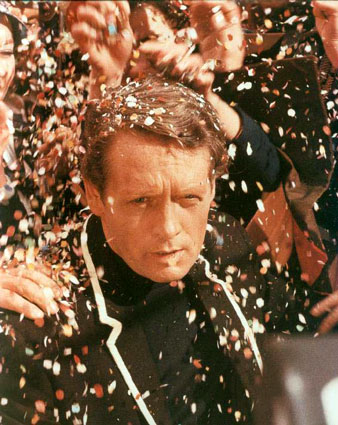

Indeed, one of the most important science fiction television series of the decade was the very surreal show, The Prisoner, which starred Patrick McGoohan. The Prisoner single-handedly put an end to the romance of the spy thriller. I Spy, The Man from U.N.C.L.E., Our Man Flint, even Get Smart were all dealt a mortal blow by what The Prisoner really suggested about Cold War politics as well as the power of governments to manipulate individual lives for its own purposes.

The "real" Village is actually a holiday resort in Portmeirion, Wales.

In The Prisoner a secret agent, and presumably a British citizen, is kidnapped by an unknown agency and kept at a place called "The Village," isolated away from the rest of the world. The keepers of the Village are never identified; they could be British or Soviet or rogue agents. And little else is known about Prisoner himself. Was he merely quitting the British Secret Service because he was tired of his job or was he in fact about to defect? The Prisoner is very Kafkaesque in its themes and it became a stunning metaphor for the ultimate corruption of government agencies by the end of the 1960s.

And where did all this distrust of government come from? It certainly wasn't present in the 1950s. Much of this paranoia appeared right after the Warren Commission released its results of their investigation into the assassination of JFK in 1964. Many who read the Warren Commission Report (such as the Instructionator) found it either an innocent botch by incompetent bureaucrats or a thinly disguised cover-up. As was pointed out by attorney Mark Lane in his 1965 book Rush to Judgment, there was not a shred of forensic evidence or eyewitness testimony that suggested that Lee Harvey Oswald had shot a rifle that morning of November 22nd, 1963. Had Oswald gone to trial, he could not be directly linked to Kennedy's death. (Officer Tippett's death is another matter.)

Later on, Jim Garrison, a New Orleans attorney, would attack the Warren Commission from a different perspective, one of dissident Cuban unrest and Kennedy's bungled Bay of Pigs adventure to unseat Castro. The hue and cry cast up by critics both at home and abroad was enough to cast doubts on the integrity of United States government officials, including President Johnson and all the succeeding administrations in Washington. Nor did the American public react well when Nixon began bombing Cambodia---a sovereign nation and a U.S. ally, let's not forget---in May of 1970 without telling anybody except the Air Force. It only seems odd now that no one in American these days seems particularly upset that George Bush invaded Iraq without a declaration of war.

But the fact is that men in power--and America is not immune here--have always abused power whether it was given to them by the people or whether they took it for themselves. So it always was, so shall it always be. Science fiction allows us not only to speculate, but it also allows us--and sometimes compels us--consciously or unconsciously to express our fears and dreads in a fictive setting. Stories about Mars or the far future, or stories about about alien invasions, are usually just metaphors for life as it is lived (or as it perceived) in the present day. The movie, V for Vendetta, released in the spring of 2006 is based on a graphic novel written in the 1980s that criticized the government of Margaret Thatcher in Britain. It went to war with Argentina, it destroyed all labor unions in the country, and clamped down on the economy. But V for Vendetta clearly has resonance with the second half of the Bush presidency in America. Seen this way--seen as metaphor--it's quite a disturbing movie.

Even though Mark Lane's conspiracy book was (and still is) controversial, as are the legions of conspiracy books that have come out over the last 45 years, I'm not suggesting that any of their accusations are true, but they did begin the notion, perhaps we could call it an "urban legend," that there is perhaps a "second government" running what we perceive as the real government of the United States. At the very least these conspiracy theories suggest that our elected officials are operating on a level of perception that we are not, and this could be to our detriment. This particular conceit is what informed Chris Carter's television series, The X-Files.

There was nothing new in this concept though, other than it struck a chord with citizens of the United States. People have been seeing conspiracies since the dawn of time. Indeed, Aleister Crowley in the early 20th century was on the forefront of imagining all sorts of conspiracies, from the cabal of Jewish intellectuals that he believed controlling the banking industry of Europe to the secretive Freemasons, whose rituals, he believed went all the way back to ancient Egypt. Hitler will find grist for his mill in Crowley's anti-Semitism and the present-day Nazi movement still carries the torch for these beliefs.

The real problem, though, is when the average American loses faith in his or her elected officials--or the "system" at large--that the trouble really starts. Typically, in situations like that, governments have to forcably make sure their citizens conform and typcially this is done through a police state or something like the SS in Germany of the 1930s. Indeed, America had become so strengthened during World War II that its presence could be felt in every region of the country as opposed to the 1930s when the federal government was practically nonexistent no matter where you went. There was no FCC, no Interstate Commerce Commission, no FAA, no FDIC. Only the post office delivering the daily mail was the average citizen's contact with the federal government. The Great Depression and FDR changed all of that. To many individuals, this "sudden" presence of the government in our everyday lives after WW II only spelled trouble and individual accountability through the IRS, social security, and selective service.

Who could you trust anymore? During the 1980s one scandal after another rocked Wall Street as various businesses were bled dry by corrupt CEOs and CFOs and the later collapse of Enron and Global Crossing only a few years ago have shown us that there are many aspects of our civilization that, without careful monitoring, could get out of control and do real damage to people's lives. We now live in a world where the foibles of a single multi-national company could undermine entire economies. (Or sustain them!) Remember, it was in the 1950s that Charlie Wilson, once the president of General Motors and Secretary of Defense in the Eisenhower administration, who said: "What's good for GM is good for the country." Could Haliburton now become the GM of the future? Haliburton will certainly have some influence over the future of Iraq. Who would have thought this a hundred years ago? Colonial powers, once sustained by entire governments (Holland, Spain, Britain, France, etc.) now take the form of global corporations. In the future, the world may not be run by empires or nation states, but corporations and conglomerates. (Or not. Imagine a world run by a series of Caliphates.) Microsoft, after all, have a greater net worth than most countries in South America and warfare in the future might take the form of hostile takeovers and leveraged buyouts.

These are mere speculations, but that's what science fiction writers have been doing for two centuries and they are very real.

But is it any wonder any more that some people think that no one's at the wheel? It's one thing to have technology out of control. What about a government out of control? Or an idiology? Trickle-down Economics didn't work in the 1980s. Will it in the 21st century? Think of this: Imagine a 27 trillion dollar economy such as ours. Also imagine just 2% of the people of our country in possession of 68.2% of our capital wealth. Is it 1984? Brave New World? Not at all. It's happening right here, right now. America, not Mexico (where the percentages are much worse). When revolutionaries stormed the Bastille in France on July 14th, 1789, they were peasants, the poorest of the poor who were angry at the corruption of an aristocratic bureaucracy that had seen to it that the king and his well-heeled friends kept 98.1% of the total wealth of France and whenever taxes needed to be raised to mount an army (in order to protect themselves--sound familiar?) they fell upon the poor. By the time of the French Revolution, no aristocrat paid taxes of any kind. It was written into to the actual law.

What little money there was, wasn't sunk into factories or invested in any way in the country at large. It was kept in private treasuries. A bloody revolution was thus fought and France has never had a king or queen or an aristocrat running the country ever since. The same is true for Russia.

To be fair to our wealthy citizens (and the true promise of the American dream), most of our 27 trillion dollars is heavily invested in industry and technology at both home and abroad and not in expensive paintings and stockpiles of gold and jewels in estates on Long Island and in the Hamptons. And our wealthy do pay taxes. Still, is it any wonder that even here in the land of the free that there is a part of the population that naturally distrusts the government? It wasn't always so.

And then there is an ongoing belief that our government is also covering up knowledge of UFOs, and has been doing so since Kenneth Arnold's 1947 sighting in Oregon. (UFOs, cattle mutilations, Bigfoot, you name it.) When Watergate comes along in 1973, whatever reverence we might have had for our elected officials completely vanishes because guys like G. Gordon Liddy, John Mitchell, and John Dean decide to screw with the democratic process. As Sinclair Lewis says, it can happen here.

Kenneth Arnold and a drawing of what one of the "ships" he witnessed on June 24th, 1947. He was flying at 9,000 feet near Mt. Rainier when he witnessed a procession of nine "strange" objects. He later said they looked like "saucers" skipping over a lake. Thus, the term "flying saucers" came into being. Curiously, little of the lore of UFOs has made it into written science fiction, perhaps because the typical UFO encounter is a bit boring.

***

At this time in the early 1960s science fiction was beginning to prosper, mostly because publishers began to see science fiction as a viable publishing endeavor and publishing houses which previously did not have a science fiction line began creating them. Or put differently: there was a lot of money out there to be made because there was a hungry audience ready to read just about anything that looked good. Thus, by the 1970s, science fiction books would begin to appear on The New York Times Bestseller's List (something quite common these days).

More writers than ever were entering the field, and few, if any, were strictly in the Campellian camp. Moreover, fantasy began its rise at this time, simply because the market had opened up once the reading public discovered the novels of J. R. R. Tolkein. This leads us to a very important (though often ignored) publishing phenomenon that came about in the early Sixties. This was the rediscovery---and in many cases, the rehabilitation---of the great pulp heroes of the 1930s. And we start with Edgar Rice Burroughs.

|

|

|

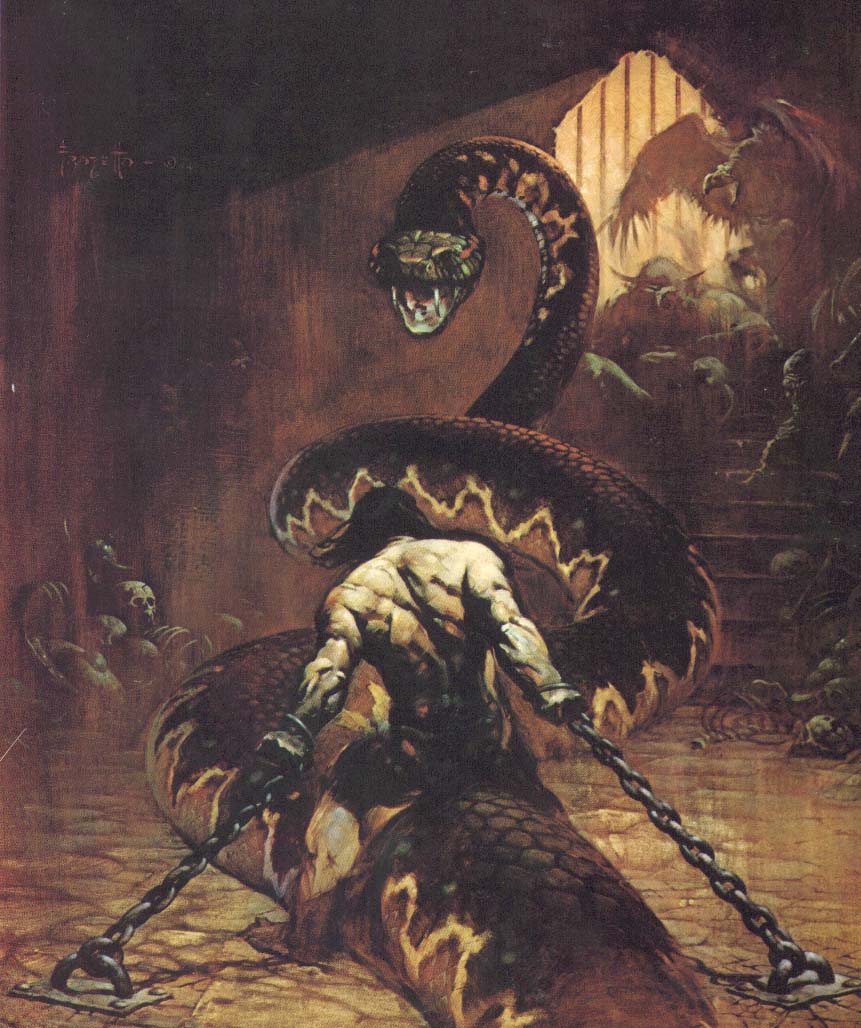

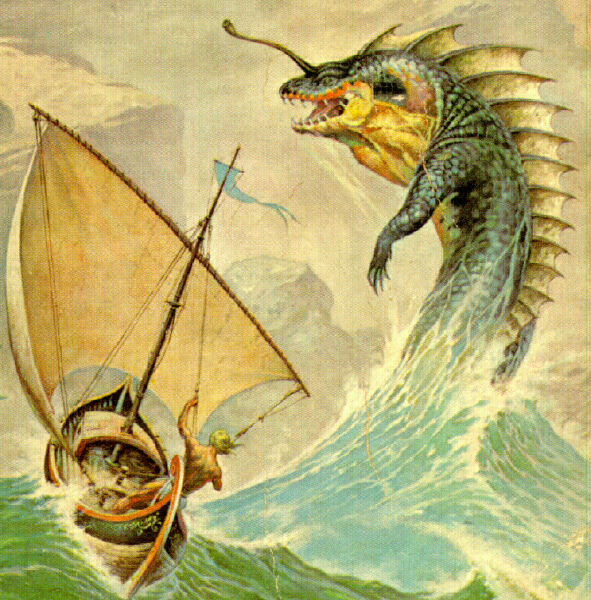

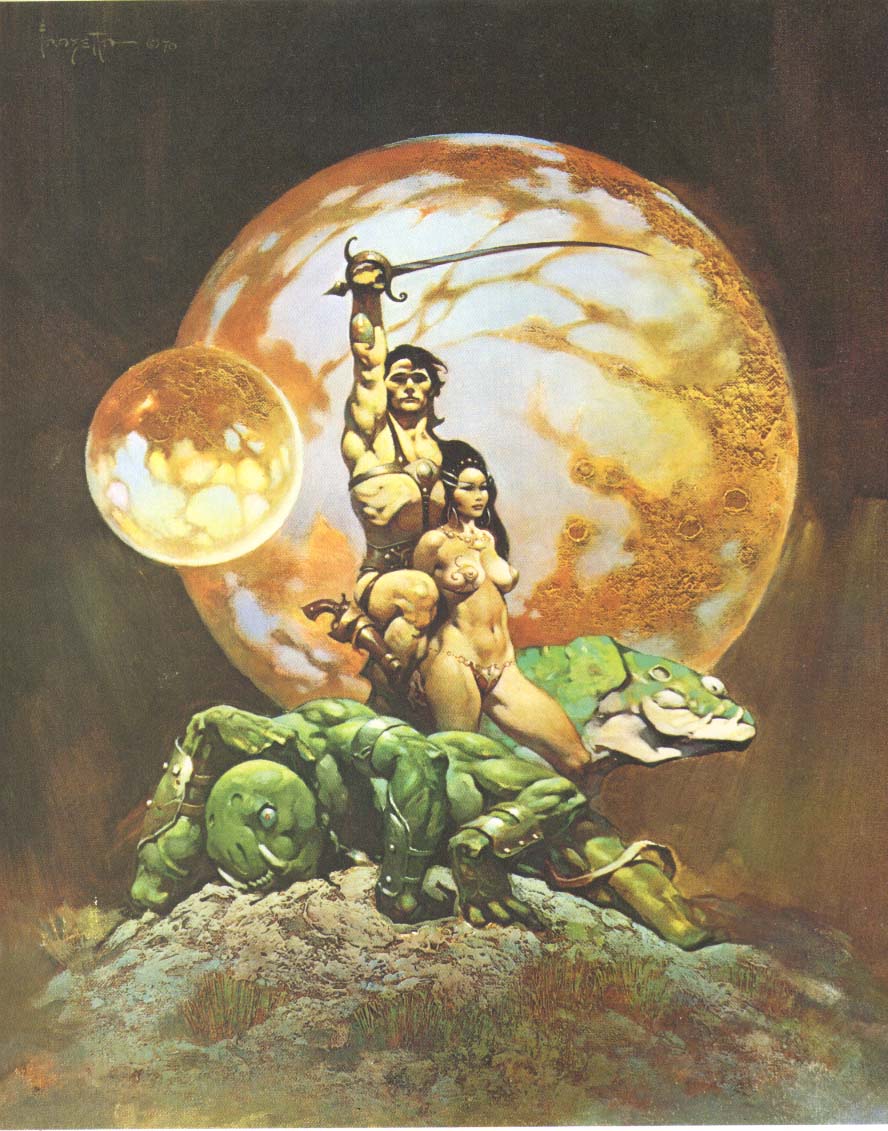

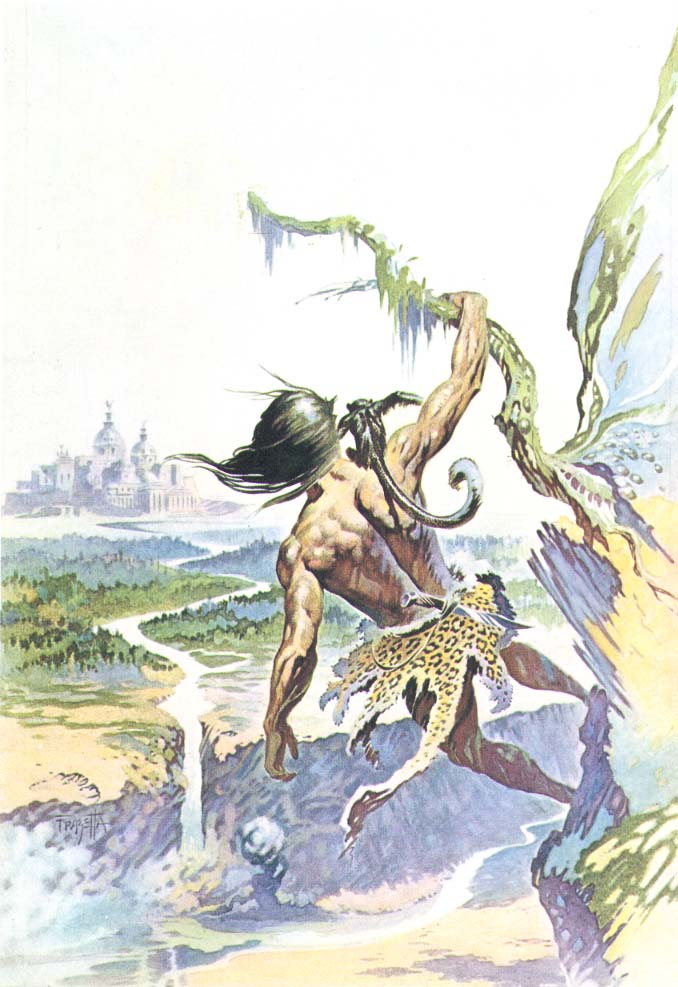

Frank Frazetta's covers for Ace Science Fiction in their Edgar Rice Burroughs reprints. Left to right are Carson of Venus, The Princess of Mars, Tarzan and the Lost Empire. Frazetta revolutionized the art of fantasy illustrations. Click on any picture above to go to a fantastic site devoted to Frazetta's work.

In the early Sixties, Ace Books began reissuing the pulp adventure novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs. Burroughs had always had a following mostly because of Tarzan. Yet his science fiction adventures were less well known to younger readers (the person writing these words, for example). Previously, the tales of John Carter and those of Carson on Venus, to say nothing of the Moon Maid and all those people who lived in Pellucidar, only existed in expensive hardbound editions available only in libraries. A wider (and younger) market had yet to be tapped.

Ace Books obtained the rights to all of Burroughs' novels and reissued them all in about a four-year period. More importantly, Ace published them with brilliantly evocative covers by Frank Frazetta. As such, Ace almost single-handedly created the market for fantasy in one bold stroke. Ace Books had originally entered the paperback market in 1953, publishing mostly westerns in a "double" format: two novels (actually novellas) back to back, with one novel upside down to the other. Ace also published science fiction in the "double novel" format.

See the link at the end of this Lecture for the Leo and Diane Dillon covers

to the Ace Science Fiction Specials.

However, in the 1960s, Ace became a major publisher of science fiction with their crowning achievement being the Ace Science Fiction Specials, of the late 1960s and early 1970s, that were edited by Terry Carr with extraordinary covers by Leo and Diane Dillon. Some of the most important novels in the science fiction field appeared as Ace Science Fiction Specials--Ursula K. LeGuin's The Left Hand of Darkness, John Brunner's The Jagged Orbit, Philip K. Dick's The Preserving Machine and Roger Zelazny's Isle of the Dead.

And let's not forget Conan the Barbarian. Conan was the brainchild of Robert E. Howard, friend and soul-mate of H.P. Lovecraft. Howard, a prolific pulp writer from Texas, published most of his stories during the 1920s and were a staple of Weird Tales magazine. He committed suicide in 1936 and never witnessed the impact his fiction (or his famous barbarian) had on the field.

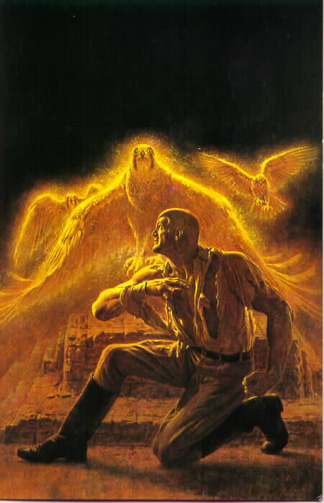

Frank Frazetta's stunning cover to the Lancer Books 1967 reprint of Conan the Usurper.

Though Howard's writings experienced a brief revival in the early 1950s, Howard was really put on the map when Lancer Books, a small New York paperback company (now deceased) published nearly all of Howard's Conan stories, edited by Lester Del Rey and Lin Carter. Lancer Books also employed by Frank Frazetta to illustrate the Conan covers. Frazetta's art appeared on a number of fantasy adventure books in the 1960s, but in 1964 the pulp revival really took off when Doc Savage, the greatest pulp hero of them all, came back to life.

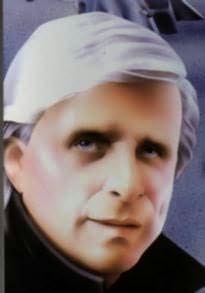

Image of the original Doc Savage, Jr. by Walter M. Baumhofer,1934.

In 1964 Bantam Books decided to resurrect Doc Savage in a numbered series format of paperback books. At first they had only intended to publish eight stories, but when the series unexpectedly took off, Bantam committed itself to publish all 187 novels that had been originally published from March of 1933 to November of 1949. No publisher had attempted a numbered series before, so it was very much a publishing risk on Bantam's behalf. The generation that had read Doc Savage Magazine in the 1930s was very much alive, but the real money lay in getting newer readers who were born after the era of the pulps (your instructor). Bantam did this the same way that Ace and Lancer Books did with their Burroughs and Conan series. They "jazzed up" the image of their character for a younger, television-oriented age and soon every pulp hero found a new publisher in New York. Doc Savage was the most successful of them.

Bantam, however, wanted a more updated, "modern" Doc Savage and employed commercial artist James Bama to give Doc Savage a makeover. Bama's Doc Savage was a golden-skinned, blond-haired physical superman with a pronounced widow's peak. With riveting golden eyes and torn shirt, this Doc Savage meant business. And off the series went, exposing a whole new generation to the fantastic literature of the 1930s (to say nothing of some pretty spectacular writing, especially in The Lost Oasis and The Thousand-Headed Man).

Click on the image for just one of many of Doc Savage sites.

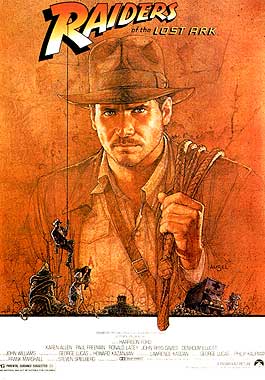

The influence of the Doc Savage stories and the central character cannot be measured, but many movies have been made using the Doc Savage archetype including The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai and Raiders of the Lost Ark.

|

Others have seen the archetype (a charismatic leader and a team of specialists) in Arnold Schwarzenegger's Predator and the most recent League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow. It's an archetype that is particularly American and comes out of a typcially American "can do" attitude that really came of age in World War Two when anyone who could, did--because they had to. There were real enemies abroad at that time.

But if the Doc Savage stories seemed a little dated as the Sixties wore on, it was only because the world was changing at a horrendous rate. Everything seemed to change at once, both at home and abroad. Music, movies, fashion, even morals felt the hammer-blows of change, even at times leading that change. And science fiction was as much a part of it as anything else.

A curious feature of this time was the way in which authors in England were evolving in directions different from those in America. If Doc Savage (and his descendants) were proactive in their responses to the crises in their fictive worlds (particularly the Spider), British protagonists were not--and perhaps never were. If you look closely at much British literature, you will find that many of its protagonists (and I'm including mainstream literature as well) find that there is little they can do in their lives to affect change. Notice that Dr. Frankenstein, even though he had the brains to make his monster, he is by and large impotent when it comes to stopping his monster from causing harm. This is true in H.G. Wells as well as Thomas Hardy, E. M. Forster, Virginia Woolf, Joseph Conrad, James Joyce, D.H. Lawrence all the way up to Salmon Rushdie. Our American archetype (as Hemingway once pointed out in a famous essay) is Huckleberry Finn who, with Jim (who also takes action), picks up and leaves. But not the characters in the works of Austen, Dickens, Thackary, George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans), and Henry James. This might be because of cultural mind-sets: the British have always found themselves in a class/caste system where one simply was what one was born as. A good British sf novel where this is true is War Of The Worlds by H.G. Wells. The main character in that novel can do nothing but run and hide. In its American equivalent Independence Day, the Americans (again, working as a Doc Savage-like team) not only take action but blow up all of the aliens. If H.G. Wells had written that screenplay (or Joseph Conrad), the aliens would have won. Easily.

In fairness to the British, however, that there are exceptions to this rule. James Bond is one of them. But when you examine British fiction of the last 250 years, you see, like Hamlet, characters who feel that they have no real latitude of movement and, if anything, are merely reactivie than proactive. And while it's true that The Prisoner does escape from the Village, the final scene leaves us wondering what he has escaped into, or if escape is even possible at all.

This is how the episode of the Simpsons starring Patrick McGoohan ends. We are all ultimately living in The Village and nothing is what it seems. Certainly we are left with the clear impression that we have no real control over our lives.

All this, as the French would say, is Man's existential plight. There is little, if anything, one can do about one's fate. Governments are so huge, yet run by so few, that the common man and the common woman cannot possibly hope to have any real kind of freedom--including freedom to think your own thoughts. (This, remember, is what makes Robert A. Heinlein's story "They" so effective.)

One author who falls neatly into this existential tradition is writer J.G. Ballard. Ballard published stories in Michael Moorcock's New Worlds in England and started dazzling both British and American readers with his slightly askew view of the universe. He is known for a series of SF disaster novels, The Wind From Nowhere, The Drowned World, The Drought, and The Crystal World and a collection of stories centered around a mysterious resort called Vermilion Sands--all of which depict extraordinary worlds pretty much beyond the control, even understanding, of the common man. A world wildly out of control can be found (published about the same time) is Brian Aldiss' crazy Barefoot in the Head in 1969 where Europe is recovering from the Psychedelic Wars.

Yet Ballard never stuck to one genre, publishing both science fiction and mainstream fiction with equal flair. He's one of the few genre writers to have made the leap into the mainstream with little or no effort. His novel Empire of the Sun (1984) is about Ballard's own childhood, at the mercy of the Japanese in China, where he grew up. (This was made, as you probably know, into a Stephen Spielberg movie.)

|

|

|

You will also have noticed by now that science fiction stories (at least the one's I have selected for your anthology) tend to focus on "the common man" or just regular folks caught up in something much larger than they are. Gone are the heroes of "Who Goes There," the scientists of the pulp era who were equipped mentally and physically to meet any challenge.

Instead, by the 1960s we find ordinary people in the grip of something they can neither explain nor overcome (Jerome Bixby's "It's a Good Life" is a perfect example here). The characters in J.G. Ballard's stories generally find themselves in the worst of all situations: reality itself has gotten out of hand and all a person can do is cope and hope for the best. The fun in reading "The Watch-Towers" is trying to figure out A) what the Watch-Towers really are, B) how they got there and C) whether or not Ballard intends us to take them literally or metaphorically. Certainly the plight of the main character seems real enough. But what the hell are the Watch-Towers? Humans seem to be inside them, but who are they? Perhaps, in the end, the Watch-Towers can be taken as both literal and metaphorical. Or not. Who knows? Ballard's fiction, like that of Philip K. Dick, often resists easy categorization and that has brought both authors a late, but devoted, readership.

|

J.G. Ballard |

|

And this is an important point. The actual prose of science fiction stories has historically tended not to be difficult. Gernsback went for all kinds of "gizmo" SF in Amazing Stories, but John W. Campbell Jr. did not. Still, this is the curse of the pulp era and one of the reasons science fiction is so often maligned in the academic world. As it is (and as you know if you've read Conrad or Melville) much of mainstream literature is extremely difficult. Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, even Joyce Carol Oates require patient examination and patience is something most Americans, and certainly most readers of pulp fiction don't have much of. (And, yes, you can end a paragraph with a preposition.)

Because of this science fiction has been hard put to prove to the rest of the world that it's not necessarily a genre for 12 year-old boys and that the stories are simplistic or crude or materialistic. (Virginia Woolf thought this of H.G. Wells without really defining what she meant by "materialistic." My guess is that she meant anything that smacked of having a plot or was intended as some form of mere entertainment.) Still, to quote Sturgeon's law: Ninety-five percent of everything is crap.

But the stigma of being a genre known for its bad writing began to lift in the 1960s when the entire field fell under the influence of editors such as Michael Moorcock, Terry Carr and, later on, Harlan Ellison, who encouraged their writers to write at the absolute peak of their ability. As such, the first genuinely difficult science fiction begins to appear at this time. John Brunner's Stand on Zanzibar (1969) and Ursula K. LeGuin's The Left Hand of Darkness (1970) won Hugos for the best novel of their respective years, yet both pose unfamiliar rigors for the average reader.

|

|

These are not "pulp" adventure stories and tended, as is the case with Le Guin, to resemble philosophical novels such as those of Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus (and Philip K. Dick would come closest to resembling Gogol or Kafka).

But these novels could never have been published a mere decade earlier. By the early 1960s, though, the audience for these books was in place. This audience was now in college, musically hip, and politically savvy. And not a small part of that audience was dabbling in the drug culture of the time, experimenting with the frameworks of consciousness, looking to see if there were other ways of characterizing human experience. Science fiction was no less affected. This was a culture-wide change and a great deal of mainstream literature had undergone the same changes.

In the real world, grownups such as Thomas Pynchon, Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Carlos Castaneda, Robert Coover, Paul Bowles and William S. Burroughs (no relation to Edgar Rice Burroughs) were burning up college English classes with their wit, wisdom, and surreal visions of realms hitherto unimagined. Overseas Italo Calvino was writing his fantastic fictions; in South America, Jorge Luis Borges and Gabriel Garcia Marquez were inventing magical realism all on their own.

And how did this sea-change come about? One reason for this was that right after World War II, everyone started going to college. College, something heretofore inaccessible by any but members of the upper classes, became a middle-class goal. Much of this came about because of the various veterans benefits enacted by Congress in 1946 and 1947 to get veterans into college so they would have usable skills on returning to society. In simple fact, the American reading public became smarter and it showed in the level of sophistication in poetry, fiction, drama and cinema, not only in America, but in Europe as well.

The other factor at this time that became a major influence in the culture of the era was drugs. Just about everything in popular culture became influenced by people (writers and civilians alike) using marijuana, LSD, and other drugs. Many literary figures dabbled in the use of drugs, not the least of which was British writer and philosopher Aldous Huxley who saw psychotropic drugs as a means to gain access to a higher reality. Huxley, the author of Brave New World, also wrote a seminal work on mescaline and peyote called The Doors of Perception.

Aldous Huxley

Quite a lot changed because of hallucinogens. Everyone from the Beatles on down (or up) seemed to be doing them. Even cinema directors experimented in strange modes of filming, sometimes inventing modes of storytelling that moved beyond the logical and the linear (this would lead to movies of the 1990s such as Pulp Fiction that tells its story in a fractured manner) . During the 1960s the films of Fellini, Kurosawa and Bergman were changing the way directors told their stories. This happened in science fiction as well.

This isn't to say that the science fiction field became flooded with drugged-out literary experiments such as Brian Aldiss' aforementioned Barefoot in the Head (1969) and Thomas Disch's tour de force also of 1969, Camp Concentration. But we must remember that writers are also part of the culture and their points of view often show up in their fiction. Some did drugs; most didn't. Few who did drugs found that it affected their writing. Others were quite impressed by the experience. (We'll talk about Philip K. Dick in a minute.) But the writing in the field did change during this time and many brave editors advocated such writing. It certainly found a place in the hearts and minds of readers.

Still, many writers emerged whose simplicity of writing style and sheer sanity seemed to be at the opposite end of the stylistic spectrum. Writers such as Samuel R. Delany, Jr., Roger Zelazny and R.A. Lafferty are almost the complete opposites of Aldiss, Disch and LeGuin. These writers managed to emphasize the simple art of storytelling without letting the words get in the way.

|

Roger Zelazny |

|

Roger Zelazny has an amazingly unadorned writing style; yet his stories zip right along with both humor and poignancy. "The Great Slow Kings," a terribly funny story all on its own, gains its impact from what we all know of human folly. Like a lot of SF that appeared after Astounding, "The Great Slow Kings" suggests that humans might not be able to "make it" as a galactic species, something John W. Campbell, Jr. would never have advocated. Zelazny, like Ray Bradbury before him, wrote a number of stories that were, at their very center, tragic. His stylistic simplicity belies the heart of a great moralist.

R.A. Lafferty is another kettle of fish entirely. Lafferty's forte was the short story and what short stories they were! Part fantasy, part SF, and part magical realism, Lafferty's stories inhabit a realm of their own. Few of his stories were ever meant to be taken literally, yet they all resonate with deeply conjured truths.

|

|

"A Slow Tuesday Night" is probably his most anthologized short story and its endurance in the canon lies in its clear metaphorical applications to what life in America has become today. Rock groups become instant millionaires practically overnight (they're called One Hit Wonders) then fade away, never to be seen or heard from again. Fads in clothing-or anything else for that matter-appear and disappear in the blink of an eye. (Like, whatever happened to Hootie and the Blowfish and Soundgarden and Alice in Chains and Stone Temple Pilots?) This wonderful short story has all the satiric ring of Vonnegut's "Harrison Bergeron" which describes yet again another aspect of the American culture. (I would equate in spirit many of R.A. Lafferty's short stories with those of magical realist Jorge Luis Borges. They are that good. Lafferty, however, has more humor than does Borges.)

One writer who has had a major influence on the science fiction field as both an editor and writer is Frederick Pohl. Pohl was one of John Campbell's competitors in the early 1940s, when Pohl edited Astonishing Stories and Super Science Stories, pulps that ultimately did not survive the paper shortages of WW II. Pohl was then an agent for SF writers until he started writing on his own in the early 1950s. His most famous collaboration was with C.M. Kornbluth. In 1952 they wrote The Space Merchants, a classic send-up of the advertising business. His most famous series remains the Gateway books.

|

Frederick Pohl |

|

"Day Million" is Pohl's most anthologized short story and represents Pohl at his satiric, succinct best. This story suggests (as does H.G. Wells' The Time Machine) that the future of human beings might be nearly incomprehensible to those of us alive now, that perhaps we will need to redefine what it means to be a human being. "Day Million" is also one of the first stories in science fiction to explore the complications of human sexuality in a serious, rather than a titillating way. The Sixties, in fact, saw a great many SF stories exploring human (and sometimes alien) sexuality. The decade ended with Ursula K. LeGuin's breakthrough novel, The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), which explored the cultural ramifications of a blurred sexuality in a human-evolved species on a planet called Winter. The greatest science fiction satire of modern sexual mores was captured in Roger Vadim's 1968 romp Barbarella, starring a young Jane Fonda.

Barbarella began as a French comic book hero then was translated into a somewhat campy movie. Camp was big in the late 1960s.

In general, however, science fiction tends to approach sex and sexuality frankly and sometimes wildly, in an experimental sense. Samuel R. Delany Jr.'s "Aye, and Gommorah" is perhaps the best short story that explores sexuality. Other writers who explore sexuality (who are not part of this class) are Philip Jose Farmer, Robert Silverberg and Norman Spinrad. Sexuality explored from the perspective of politics and male domination, however, is a quite universal theme and I would recommend Sheri S. Tepper as a place to start within the field. Outside the field, I would go to Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale of 1998. Though not published as science fiction, it most clearly is.

Our final two figures have had an ongoing and lasting effect on the science field and they have helped in convincing the world that science fiction is actually literature and not the juvenilia that academe has traditionally claimed it to be. These writers are Philip K. Dick and Harlan Ellison. Philip K. Dick's writing career started in the early 1950s when he attempted to become a mainstream writer. When that failed, his friend Donald Wollheim suggested that Dick turn his sights to science fiction. Dick became an immediate hit with readers and produced an extraordinary body of work in both short fiction and the novel. His fiction has been called paranoiac, visionary, transcendent, and just plain crazy. All of those certainly apply.

Dick's novels and stories are virtually indescribable and they usually involve some sort of reality-bending crisis in the life of an ordinary individual (as in the recent movie Minority Report). Dick's writing is meticulously crafted, but his plots are absolutely unpredictable (rare for a field of almost formulaic plotting conventions). And sometimes the good guy doesn't always triumph in the end. In fact, there are times when nobody wins. Still for all that, Dick became one of the most respected writers the genre ever produced.

The story I've chosen, "We Can Remember It For You Wholesale" (which was made into the movie Total Recall), takes an ordinary man and thrusts him into a world he can't control. In fact, that world (an implanted vacation scenario) turns around and bites him in the ass-him and everyone else nearby. This is a wonderful Frankenstein story that takes several digs at science and technology, with not a few digs at American commercialism.

Another Frankenstein story is Harlan Ellison's brutal "'Repent, Harlequin!' Said the Ticktockman". The "monster" this time is an efficiency-oriented future world that ends up serving no one's interests, except perhaps the "Man" (which would be in this case the Ticktockman). Oddly, this story is very much in the vein of the Heinleinesque hero facing a tyrannical system. This is also a reflection of Ellison's own pugnacious personality.

Ellison's career began in the 1950s and he has created an enormous body of work, mostly in the format of the short story and novelette. But his has written several million words in articles, newspaper columns, screenplays, and teleplays. There is no kind of writing Ellison has not touched upon (except maybe cookbooks, but I could be wrong in this). He has even scripted a number of issues of a wide array of comic books. Ellison's stories tend to be satires or monstrous visions of the future, and they are all written in one of the most characteristic writing styles in the field. His stories grab you by the short hairs and takes you where you don't want to go, but go there you do.

I've also chosen Ellison to be our last author of study in this course for another reason. And this reason has to do with a line of demarcation between Modern Science Fiction and Contemporary Science Fiction, which I discussed in the General Introduction To The Course (Contemporary SF being the literature of 1967 to the present).

As you've seen, the late 1960s in both America and Britain was a time of great experimentation in all of the arts. Movies changed, music changed, the world was rocking and rolling to the beat of Huey helicopters prowling the skies above the rice paddies of Vietnam. In England, New Worlds was giving Brian Aldiss, John Brunner and J.G. Ballard a chance at spreading their literary wings. All of which led to the creation of a literary phenomenon called the "New Wave."

|

|

Ellison's prodigies of old.

The latest incarnation of Dangerous Visions. This is a book I highly recommend to you. It should be an essential part of your library.

But back in America, Harlan Ellison's contribution to the New Wave was a book he edited called Dangerous Visions. Ellison convinced Larry Ashmead at Doubleday to do something that had never been done in publishing before. He convinced Doubleday to publish a massive book of original science fiction-not a reprint anthology- but it would be a book of science fiction stories so radical that they never would be accepted by the normal SF magazine outlets. This book, when it came out, rocked the science fiction (and publishing) world. Among its 33 extraordinary stories were the award-winning "Aye, And Gomorrah ..." by Samuel R. Delany, "Gonna Roll the Bones" by Fritz Leiber and "Riders of the Purple Wage" by Philip Jose Farmer. Indeed, Dangerous Visions might be Ellison's lasting achievement. Not even his own radical fiction has had the impact that Dangerous Visions has.

Whether science fiction needed a shot in the arm in 1967 is a matter of debate because fine science fiction was already being produced by dozens of wonderful writers. It was also evident that by 1967, the "hard science" story advocated by John W. Campbell Jr. was no longer the only kind of story writers wanted to write and readers wanted to read. Science fiction had expanded right along with the general culture even if the influence of John Campbell still resonated throughout the field. Remember that Star Trek, the television show, ran from 1966 to 1969 and it was based on A.E. Van Vogt's Voyage of the Space Beagle, itself a product of Astounding Science Fiction. In fact, science fiction remained conservative in cinema until the 1980s when Blade Runner, directed with great stylistic flair by Ridley Scott, came along. Indeed, science fiction cinema today seems to be advancing by greater leaps and bounds than the written word, perhaps due to the advances in special effects technology and CGI software. Steven Spielberg's Minority Report is a grand stylistic romp as is Terry Gilliam's 12 Monkeys, and The Fifth Element is just plain fun to watch.

As it is, science fiction will undergo a few more changes in the Contemporary Era (1967 to the present), but if you've tracked these lectures all the way to this point, you should have a solid foundation of the origins of science fiction and how it came to be what it is.

I have one final comment. You will have noticed that I have virtually (though not entirely) ignored women---or more properly speaking, women writers---in this course. I wasn't quite "ignoring" them. Until the late 1960s, after the period covered in this course, women authors had not entered the field in any huge numbers or written stories as powerfully significant as the men in the field up to that time. Then again, for years it was mostly an adolescent male's domain. Even movie serials of the 1930s and 1940s were mostly aimed at boys (and white, male boys, at that). Not so anymore.

As always in our culture, it takes a while for minorities and women to catch up to most things. So, too, science fiction. But they are with us now. With Judith Merril and Catherine L. Moore already mentioned in this course, we have Ursula K. LeGuin, James Triptree, Jr. (the pen-name of the incredible Alice Sheldon), Kate Wilhelm, Andre Norton (Alice North), Katherine MacLean, Anne McCaffery, Zenna Henderson, Joanna Russ, Octavia Butler, Pat Murphy, Patricia Anthony, Pat Cadigan, Connie Willis, Pamela Sargent, Linda Nagata, Sherri S. Tepper and dozens more whose stories I'd focus on in a separate course of Contemporary Science Fiction, which would range form 1967 to the present. Perhaps ASU will let me design and teach that course some day. Still, the science fiction field only reflects the culture of its times, and when the times change, so too does science fiction. (It should be pointed out that today women virtually dominate the fantasy genre. If you read fantasy, you already know this.) As it is, there are almost an equal number of female science fiction writers as there are male writers today.

At the very least, I recommend that you track down the novels of Ursula K. LeGuin, the short stories of James Triptree, Jr. and when you have nothing else to do with your life, read Sherri S. Tepper's novel, Grass; then run out and buy Pamela Sargent's novel, The Shore of Women. Click here for a cool site discussing women science fiction and fantasy writers.

Now get busy.

Recommended Science Fiction Novels