FIRST LECTURE

Early science fiction begins when Mary Shelley published Frankenstein in 1819. Science fiction came about when western civilization had both a populace that wanted to read (and that could read) and the means by which stories were delivered. Some were in the form of books, others came in the form of serialization in magazines. The main venue or format for all fiction until at least the 1830s was the novel. The literary journal or even the popular magazine as we know them today (The Atlantic Monthly, Harper's, or The New Yorker, for example) had yet to be invented. Gradually, over time as the population became more literate and interested in worldly affairs, magazines became more frequent.

Harper's Weekly appeared in the 1850s and are still going strong today.

Newspapers and pamphlets were common throughout the 18th century (the American revolution was facilitated by pamphleteering), but all fiction came in the form of books. In fact, in Lecture Three I will discuss the great pulp magazines, which appeared in the 1890s which will eventually become the main breeding ground for all genre fiction.

***

Science fiction made its major (and first) impact through the novel. The novel, as an art form, had already evolved by Mary Shelley's time. It wasn't quite in its infancy, but it was still a toddler. There had always existed short stories of linked narratives-The Canterbury Tales, the Decameron, Aesop's Fables, etc. But a narrative work in prose (not poetry), consisting of character development within a structured framework, or plot, is a creature of 18th century England. Earlier narrative vehicles masquerading as novels were actually linked episodes written over an author's lifetime. Don Quixote written in 1615 is one such book, Lady Murasaki Shikibu's massive Tale of Genji, written in 11th century Japan, is another.

Pablo Picasso's famous drawing of Don Quixote and his trusty side-kick Sancho Panza.

Some critics hold that even the The Iliad and The Odyssey (written sometime in Greece around 750 B.C.E.) are novels, mostly because of their complicated narrative structure and emphasis on character development. Even so, many critics believe that Samuel Richardson (1689-1761) is usually credited with inventing the novel. His books include Pamela (1740), Clarissa Harlow (1748) and Sir Charles Grandison (1753) and all were written in an epistolary style (a collection of letters that, in sequence, tell a story), for reasons of verisimilitude which the readers of Richardson's time demanded. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein will follow in Richardson's narrative footsteps.

Before we get to those novelistic footsteps we need to talk about the gothic novel itself. The word "Gothic" comes from medieval times and refers to the cultural influences of the Goths who invaded Europe starting around 400 C.E. Goths in one form or another conquered Russia, Northern Italy, Poland, Germany even parts of France and Spain. Their migrations principally ended in the seventh century C.E.

The term was originally applied to literature by critics in the 18th century referring to stories about pagan magic, the occult and the supernatural particularly coming out of the Baltic region. Since then the term "gothic" has been closely associated with the Romantic movement and continues to this present day. Indeed, one of the important contributors to the American Romantic movement, the Gothic tradition, and the evolution of science fiction, will be Edgar Allan Poe.

Poe will not only write science fiction in the gothic tradition, but will also be one of the early inventors of the detective story ("Murders in the Rue Morgue"). Poe is also credited with being the first person to characterize what the "short story" is and what it should do. His influence in both fiction and creative writing persists to this day unabated especially in the fiction of Stephen King.

Just as soon as Samuel Richardson publishes Pamela in 1740, Horace Walpole publishes Ferdinand Count Fathom in 1753, the first gothic novel. Ferdinand Count Fathom is replete with ancient castles, dark intrigues, and ghosts of slain lovers wandering around at night. However, when Walpole publishes The Castle of Otranto (in 1765), he uses the subtitle "A Gothic Story" and soon after that we have William Beckford's Vathek, an Arabian Tale (1786) with its allure of the Orient and Anne Radcliffe's novels, especially The Mysteries of Udolpho (1789), the first great gothic romance.

These are just a few of examples of both early novels and novels in the gothic tradition-both of which profoundly influence writers of the early 19th century, but particularly Mary Shelley, the young wife of romantic poet Percy Shelley.

Mary Shelley's father was William Godwin (1756-1836), the philosopher and novelist. Her mother was the feminist and social activist, Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797), who died giving birth to her. The young Mary married the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in 1816 and among their mutual friends was the dashing poet Lord Byron. One night in 1816 during a rainstorm in Switzerland, so the story goes, the Shelley's, Lord Byron, and another friend, the physician John Polidori, suggested they each write a ghost story. Only John Polidori and Mary Shelley finished theirs. Polidori's was called The Vampyre (published obscurely in 1819). Mary's was called Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus, and it was published in 1818, later revised to its final form in 1831. Frankenstein is very much a novel in the "gothic" tradition and is one of the lasting achievements of the Romantic movement in England.

Mary Shelley

Mary Shelley was no scientist and certainly she did not know any mad scientists. But madness, as such, she did know something about, both in the Romantic literature of her time and through her own personal experience. Madness here is taken as some sort of mental or emotional dysfunction rather than severe debilitating psychotic schizophrenia. Most of her friends were mentally---and emotionally---unstable to some degree. They were probably manic-depressives or bipolar. The Romantic poets (her husband included) wrote poems with titles such as "Ode to Melancholy" or "Dejection: An Ode" or "Lines Written in Dejection", etc. In fact, one of the great "Gothic" poems might be Samuel Taylor Coleridge's "Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner" complete with its curses and consequences that can shatter even the strongest constitution. Mary Shelley would have known that the "mind" could be a fragile thing and she would have known how the mind could actually collapse.

This, essentially, is what happens to Dr. Frankenstein in Shelley's novel. The doctor descends into madness (of a kind) when he pursues the monster he created, knowing what the monster wants to do with his life (such has have a wife and kids and a nice house in the suburbs) and the lengths to which he'll go to achieve that goal. After all, he's already killed a few people along the way. Many critics have already suggested that the real "monster" here is Frankenstein's residual guilt which inevitably drives him to pursue is demon to his death. One hundred years later Sigmund Freud will posit that guilt (through the Oedipal Complex) is the driving force of civilization.

However, another kind of "madness" may be operating in the novel as well.

Our definition of science fiction suggests that the science fiction story arises when an author begins to feel a sense of dread regarding change in their culture (or even in their own private lives). It doesn't matter that there might not be any science fiction tropes such as bizarre machinery that taps into lightning bolts. Mary Shelly would have known of the experiments being done across Europe of her own time where electricity was used to galvanize the legs of dead frogs. She would have known of Benjamin Franklin and Alesandro Volta and of their theory that all living matter was "animated" by electricity, the same electricity that snarls through the clouds during thunderstorms. The notion that a scientist could bring a dead thing back to life using the new knowledge of his time would have been an easy leap for a fervid Romantic imagination. But Mary Shelley was not interested in the technical aspects of the actual animation process itself. Instead, she focuses on the anguish that the consequences bring upon the scientific dabbler who had perhaps stepped beyond his bounds.

It's this sense of dread, this sense that the scientist has opened a veritable Pandora's Box of nightmares through his creation, that allows Brian Aldiss to suggest that science fiction begins with Frankenstein even though there aren't any laboratories with flashing lights so common to the later Frankenstein movies. But while Aldiss focuses (not incorrectly) on the gothic aspects of the novel, I want to focus on where, in Shelley's mind the story came from. She saw something or intuited something in her culture. She felt some sense of dread over what she was hearing about or reading about regarding the leaps and bounds science was taking. And usually, what she saw-and writers like her saw-wasn't good.

By the time Nathaniel Hawthorne began writing his gothic tales, stories of the supernatural, particularly associated with nature and the wilderness (of which there was plenty in Puritan New England) began to become popular with readers in both Europe and America. Notoriously, the image of the Byronic Hero -- taken from the life and adventures of Mary Shelley's friend the romantic poet Lord Byron in England -- became transformed into the image of the "mad scientist". Hawthorne uses this image frequently, as in "The Birth Mark" as well as in "Rappacini's Daughter". Of course, Edgar Allan Poe accomplishes this, with eerie results, in "The Facts in the Case of M. Vlademar". These stories are a mix of the gothic as well as that of the mad (or not-so-mad) scientist venturing into the realm of the unknown. But always the consequences are grim. That seems to be the message.

By the time Jules Verne appears on the scene, science has changed, but men and their follies have not. The Industrial Revolution in England, America, and Europe had been well underway by 1863 when Verne published the first of his "voyages extraordinaires", Five Weeks in a Balloon. Verne was born into the French middle class and was destined for a career in business (his father wanted him to be a stock broker) when his early short fiction caught the attention of Jules Hetzel, a successful publisher of children's stories. Hetzel recommend Verne to his publishers and the Voyages extraordinaires began. The loss to the stock market was our gain. From 1863 onward, Verne remained a popular writer to his death in 1905.

Jules Verne

Jules Verne not only captured the imagination of the reading public in both Europe and America, he was able to tap into the "dread" his readers unconsciously felt toward technology, particularly the technology used to advance the ideals of imperialism and war. Verne's greatest novels are treatises on humanity's penchant for looking for as many ways as possible of declaring war on itself with the hopes of eventually blowing everything up. Ironically, Verne began his career with a fair amount of optimism about the possible better uses of technology. In his later life, like Mark Twain, he would become very pessimistic and, like Twain, he would lose his sense of humor.

However, the sense of gothic horror, so common to Frankenstein, is quite missing in Verne's writing. This has something to do with the times in which Verne lived. Many believed that the nineteenth century was a century of progress and discovery. Verne knows exactly what technology can do and this is why science fiction critic John J. Pierce thinks that true science fiction begins with Jules Verne. Verne is also much closer to our own time and Mary Shelley is not. Yet Mr. Pierce is much less taken with the gothic element that Brian Aldiss sees as the main feature of science fiction. Our definition, however, is much broader and encompasses all of our writers because their stories are coming from human beings (Shelley, Verne, Wells) who dimly sense something afoot in society. For Brian Aldiss, that sense is dread and science fiction reflects that. So be it.

Jules Verne's success nonetheless lies in his ability to capture the imagination of his audience in two important realms: One is the travelogue or the trip to a foreign land. The other is the means of transport to that foreign land.

Verne uses hot air balloons (Five Weeks in a Balloon and Around the World in Eighty Days), atomic submarines (Twenty-Thousand Leagues Under the Sea); spaceships (From the Earth to the Moon). He has floating arsenals in the sky raining terror on the armies of Europe and Asia (Robur The Conqueror). In Master of the World the villain invents a vehicle that can become a jet airplane, a submarine and a land car that travels so fast that it can't be seen, a "stealth" car, in other words.

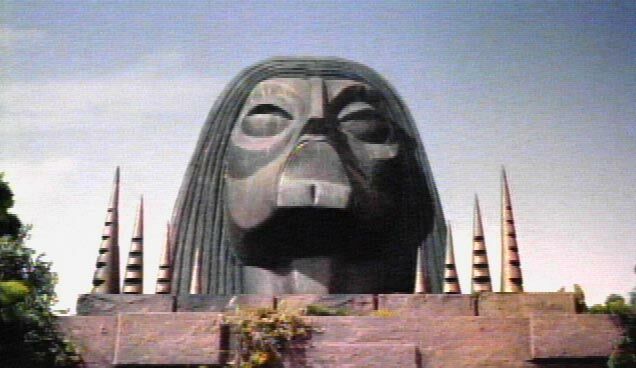

From Robur the Conqueror

Verne's characters journey to the center of the earth; they ride a comet through the solar system in Off on a Comet. In The Demon of Cawnpore the protagonists travel across India on a steam-driven mechanical elephant! Verne's imagination was seemingly unlimited. Add to this the fact that in America, Thomas Alva Edison (1847-1931) was cranking out one invention after another. More so than any other writer of his era, Verne was able to capture the Zeitgeist of the age of invention in the 19th century.

Setting aside the fantastic vehicles and fantastic lands of Verne's novels, the topics he wrote about were often quite serious. In fact, the most common theme for Verne was imperialism. France, by Verne's time, was long in decline as a major European power. But Verne saw war all around him. His greatest protagonist, Captain Nemo in Twenty-Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, hates war so much that he travels the oceans sinking one warship after another with his atomic-powered submarine, the Nautilus. Captain Robur (Robur The Conqueror) likes to drop bombs on warring armies from several thousand feet, out of the range of artillery. In The Begum's Fortune the bad guy (who is eerily a German) invents a gun so powerful that it turns artillery projectiles into intercontinental missiles that can strike a foe half a world away. This is the first mention of such a concept in world literature.

The great irony here is that Verne's antiheroes were just as loony as the people they wanted to stop. This can easily be seen in From the Earth to the Moon (1865) where a bunch of weapons makers in America scheme to build a gun powerful enough to send a projectile to the moon. Verne paints them-including a meddling Frenchman-as a bunch of idiots. Members of the Baltimore Gun Club are variously missing fingers, hands, legs, eyes-all because of ill-timed explosions of their guns and cannon. Sensibly, the people who put together the project and ride the bullet to the moon all have their parts (if not most of their common sense). Verne was never so openly silly as in From the Earth to the Moon and it would only be until the late 20th century that the greatest SF satirist of them all, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., would appear on the scene and make Verne look like a piker. It should be stressed, however, that Jules Verne was no wholesale satirist and From the Earth to the Moon was the exception, not the rule, in his work. Verne always remained a critic of his times and a fairly ruthless one at that.

H.G. Wells

H. G. Wells' vision of humanity, on the other hand, had no humor in it at all and had more pessimism than any science fiction writer will ever have. Wells' fiction was often infused with a fin de siecle despair or ennui which he absorbed from his late Victorian society. He was also profoundly influenced by the writings of Charles Darwin and the theories of evolution which had rocked the scientific world of his time. Wells was alive at an era when the British empire was also winding down and the decline and fall of nations became (within a lived-human context) something quite visible.

In fact, many critics have suggested that H.G. Wells actually invented the future, not one specific future, but the notion of a future. Of course there have been many authors who have written about the future before. These writers, however, always couched their visions in language, ideas and images that were reflections of their own times. The Book of Revelation and the writings of Nostradamus do not describe futuristic cities or space vehicles, communications satellites, or even nuclear weapons. H. G. Wells is the first author to see the future as a direct outcome of events happening in the here-and-now whether they be generated by science or politics.

The Time Machine can be seen as a critique of late Victorian optimism on the bright future of civilized Man. The savants of late 19th century England (Thomas Huxley was one) saw the term "evolution" as synonymous with the word "progress." No technology was bad. Everything was for the good . . . even if by Wells' time the intelligentsia of Britain had about eighty years to digest the warnings of Frankenstein and about thirty years to understand the dementia of Verne's protagonists. Everyone of Wells' time (at least those who believed the conceits of evolution) saw Man as the endgame of evolution. No science was bad; all technology was good. But Wells demurred. Indeed, right after he composes The Time Machine, he'll set pen to paper and write The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896) which will give us a madman, similar to Dr. Frankenstein who will try to "uplift" animals to human forms through genetic engineering. The novel details the consequences on both the animals and the people who engineered them on the island. The result is not a happy one.

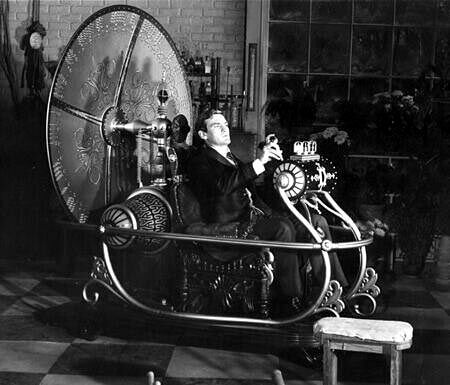

From the George Pal film of The Time Machine.

Wells, in The Time Machine, dismantles the luxuries of British upper-crust socialism and the hopeful idealism of capitalism. Not only does Wells suggest that humans will (or at least can) devolve, he also suggests that evolution is not necessarily progressive. Indeed, Wells will suggest near the end of The Time Machine that humans, and human civilization, might disappear entirely, very heretical notion in the late Victorian era. And in a predominately Christian society, this notion was not only heretical, it was thoroughly depressing. Man was bound for noble things, wasn't he? At the very least he was bound to reap his reward in the thousand-year reign of Christ on Earth and go to Heaven? Wasn't he?

(Or, to quote Yeats: "What rough beast . . . /Slouches toward Bethlehem to be born?"

Not according to Wells. And the scientifically-derived future of the Earth in The Time Machine was just convincing enough to depress everybody who read it when the book was first published as well as today.

As you can imagine, this bothered the first readers of The Time Machine. They did not want to believe that humans could evolve (or even "devolve") into some sort of brainless, beach-hugging sea urchin thirty million years hence as the novel depicts. The readers of his time (and perhaps ours) wanted to believe that the future held good things in store, that humans were "noble" creatures, made especially by God to rule over all things.

For Wells, these comforting conceits of human vanity weren't in the cards, just entropy, the heat-death of the universe--death for all the works of Man. The terror of The Time Machine is the horrifying notion that all of of our spiritual agonies, all of our brilliant artistry and all of our accomplishments might all come to nothing.