FOURTH LECTURE

The stories written from the mid-1950s to the early 1960s, a period of time s aw the end of the somnolent Eisenhower administration giving way the promise of John Kennedy's administration. What we got was a decade of extraordinary change. The threat of the Cold War and nuclear annihilation now seemed quite likely, with the actions of Soviet Russia during the short-lived Hungarian Revolution in 1956 further convincing everyone that the Soviets meant business and were quite possibly as evil and tempestuous as they seemed to be. Certainly the Hungarians had reason to think so.

At home, so did Joseph McCarthy, who saw communists everywhere and persecuted them in Congress, doing more for the "Red Menace" than the Red Menace could do on its own. By 1955 the world seemed clearly polarized into two distinct political entities (us and them) and fifth columnists were everywhere undermining society. Just ask J. Edgar Hoover. He had files galore on every major writer in the country who had any leanings toward the left. His favorites were Sinclair Lewis and John Steinbeck. Later on, he took an interest in John Lennon, The Doors, Andy Warhol and women's apparel.

One overlooked development during 1950s was the transformation of rural China into a modern communist state. Mao Tse-Tung, gifted poet and rural revolutionary, brought China into the 20th century by wresting it away from the clutches of a weak oligarchy helmed by Sun Yat Sen who, in turn, wrested it away from an effete royal line that had nothing but their own interests in mind. But almost as soon as Mao Tse-Tung grabbed hold of the government, China went absolutely quiet for a couple of decades. China would suddenly reappear on the world's radar screen when they obtained nuclear weapons technology and aggressively backed North Vietnam in their civil war with the South. Geopolitics was beginning to rear its ugly head and the comforting isolationism of the 1950s was about to end.

Also at this time, China was also at loggerheads with the Khrushchev in the U.S.S.R. because Khrushchev was a rabid anti-Nationalist, which meant that he didn't like Soviet satellite countries, China included, to retain any semblance of national or ethnic identity. The Hungarians experienced this doctrine 1956, so too the Czechs during the Prague Spring which lasted from January to August in 1968. But when China developed (stole) plans for the hydrogen bomb, the world became a much more dangerous place. Both the Americans and the Soviets began to sweat a little bit more because each had two adversaries, not one.

Soviet Tupolev "Bear" Bombers often skirted the American coast during the Cold War to test our defenses and reaction time.

The movie, On the Beach, was an international hit during this time. It was also "banned in Boston" by the Roman Catholic diocese of Massachusetts, mostly because the way the novel and the movie ends: Everyone dies. Everyone. Its bleakness was so horrifying that there were protests in many capitals of the world when the movie came out in 1959. (Critics will later respond that, while the movie was a good polemic, it didn't really show what a slow, horrible -- and painful -- death from radiation poisoning would be like. Either way, it's pretty grizzly.)

Other novels of the time, George Stewart's Earth Abides, Leigh Brackett's The Long Tomorrow, and Pat Frank's Alas, Babylon also echo the same Cold War fears. Here, it's not scientists who are out of control; it's the technocrats, those who use science (and its weaponry) to enforce public policy. When this happens, it usually has disasterous consequences.

|

|

Nevil Shute

Science fiction had, of course, been at the forefront of the dangers of nuclear radiation since Marie Curie and her husband died of radiation poisoning in 1934. She may have discovered radium, but in the end it killed her.

Then Lester Del Rey made a name for himself with the field's first story of a nuclear accident in "Nerves" in 1942 and the Fifties were full of stories involving all kinds of mutants from the giant ants in "Them" (1954) to the X-Men movies of recent vintage. What's at work here is the Frankenstein monster of the nuclear genie: once it's let out of its bottle, there's no telling what sort of damage it can do. So during the 1950s it was much easier to simply ignore the monster rather than face it. And there really was no choice. The events taking place around the world--including those in science and medicine--were clearly beyond the control of one scientist or a bunch of scientists (as in Campbell's "Who Goes There?") and the world was taking on its post-modern character. During the Fifties, in both America and Britain, a feeling developed among the lumpen proletariat (us) that society itself might be out of control and doom could occur at any time (recall "Fessenden's Worlds").

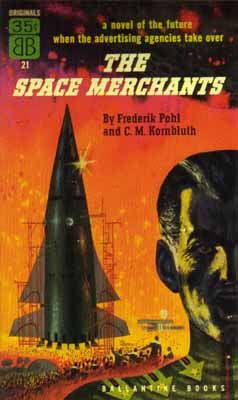

America, however, snoozed straight through most of the 1950s, and most of it, if not at the drive-in, then in front of a television set. Television and the development of the suburbs seemed to be the promise of the American dream, at least for the greater (and mostly white) middle class. Science fiction, however, often reflected this growing complacency of the (once again white) middle class, as did mainstream literature of the time. These are the great years for mainstream fiction about the new middle class published in The New Yorker. The stories of John O'Hara, John Cheever, Saul Bellow, and John Updike poignantly chronicled the plight of the middle class during this decade. Science fiction, meanwhile, often found themselves making fun of it. One of the best satires of the Madison Avenue cult of advertising is The Space Merchants by Frederick Pohl and C.M. Kornbluth.

Science fiction writers themselves were not immune to the changes America was feeling in the post-WW II years. The field begins to see science fiction taking on the role of social criticism, suggesting that perhaps our whole society has become something of its own Frankenstein monster. Certainly the ongoing nuclear testing program by the superpowers didn't do much to calm the nerves of the American public, with Great Britain and France soon to develop their own nuclear weapons. Something seemed to have gotten out of whack and everyone alive during the late 1950s felt it. Add to this the development of the intercontinental ballistic missile and field nuclear weapons and everything starts to get really scary.

It's one of the great ironies of predictive science fiction that no one saw that governments, not corporations or maverick individuals, would be the first in space and to be the first to set foot on the moon. Science fiction, of course, had been in space for over a hundred years in projectiles of one kind or another. But nearly all science fiction stories had men and women traveling to the stars under the auspices of corporations out to do business or individuals plying their own trade and playing by their own rules. Here think of Han Solo and The Millennium Falcon. In fact, this particular conceit is still being practiced today. The best current writer in this vein is C. J. Cherryh. Her novel Downbelow Station chronicles a wide group of corporations trying to get economic control of a planet (and the general space around it) with all sorts of complicated results. Indeed, in this day and age, one often finds corporations trying to rule the world rather than individual crazy people or entire governments. The RoboCop movies come to mind in this regard.

In the mind of the public, however, the space race made space travel palpably real. The public already knew about V-1 and V-2 rockets that Germany had developed during the Second World War. Everybody knew that both America and the Soviet Union were testing rockets that might someday launch a man to the moon. And, of course, the entire culture had almost a century of science fiction (good and bad) in the movies telling us where we were headed and what kinds of machines were going to get us there.

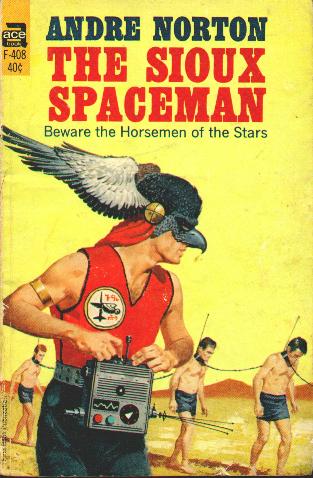

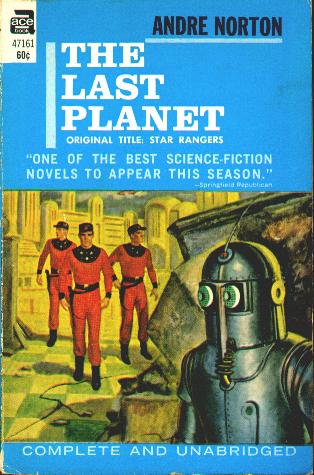

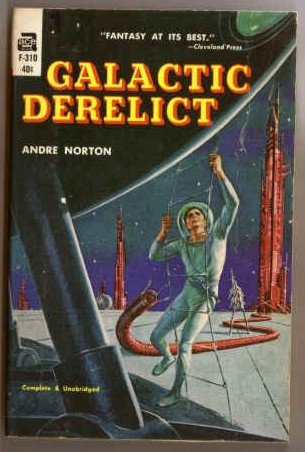

During the 1950s, television shows such as Tom Corbett, Space Cadet, Men in to Space and The Adventures of Colonel Bleep captured the imaginations of youngsters much the same way that the Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon serials captured the imaginations of kids during the 1930s. In this way, as some critics have pointed out, the genre of science fiction has a built-it growth factor. No other genre begins with readers in their early adolescence and keeps them into adulthood. Most readers come to the other genres as adults. Still, some of the best science fiction of this period came from the pen of Alice North writing as Andre Norton.

|

|

|

|---|

Ace Science Fiction was one of the leading publishers in both science fiction and fantasy. Mostly edited by Donald A. Wollheim (who later on founded DAW Books), Ace books also featured the first - and often only - editions of Philip K. Dick's novels.

Though her books weren't marketed specifically to younger readers, many who came to science fiction in this period did so through the paperback titles of Andre Norton. (This was also when Robert A. Heinlein was writing his "juveniles"; indeed, Tom Corbett, Space Cadet was actually based on the 1948 Heinlein novel Space Cadet.) What also allowed Andre Norton to have a career was the massive proliferation of paperback books during the 1950s. It was a publishing revolution that was as significant as the rise of the pulp magazine. They cost a little more than the pulp magazines of a decade earlier, but they were more durable and they allowed for the development of longer and longer novels that the pulps could not contain in one issue. (Romance pulps often serialized novels; science fiction pulps rarely did until the 1950s.)

Still, the space race was serious business, with space itself an unforgiving environment. Missiles will blow up on launch pads. Satellites will fail to make orbit and burn up on reentry. Astronauts and cosmonauts will, in their turn, die. In 1970, Apollo 13 will nearly end in disaster and the space shuttle Challenger will blow up in January 1986. All this is to remind us that space travel still is a very dangerous undertaking. Science fiction writers have always known this and many still choose to write the occasional story with a realistic edge.

Tom Godwin's classic 1954 science fiction story "The Cold Equations" is the one story that truly represents Campbellian fiction at its rigorous best. You could also argue that it is not really a science fiction story. It's the one story in your anthology that comes closest to mainstream fiction because it adheres to science as we know it today: It's what would really happen if a ship had only so much fuel and so much time to reach a destination. No more, no less. The cold equations here are the simple mathematics of objects traveling in space. They have no regard for romantic adventures or heroism. They are indifferent to Hollywood conventions of shipboard romances and daring rescues. Godwin's universe is our universe and it's a very unforgiving one.

"The Cold Equations" might be unflinchingly brutal with its harsh realities, but contrast this with Alfred Bester's "Fondly Fahrenheit," published the same year as "The Cold Equations." "Fondly Fahrenheit" clearly is not a John Campbell story. It was originally published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Astounding's main competitor at the time. "Fondly Fahrenheit" is one of a legion of science fiction stories in the Fifties that explored the nature of consciousness, perception, and reality itself. This is also one of the first stories dealing with the interface between human minds and the minds of others-in this case a robot. The Cordwainer Smith story that follows "Fondly Fahrenheit" has humans interfacing with cats, of all things.

|

|

|

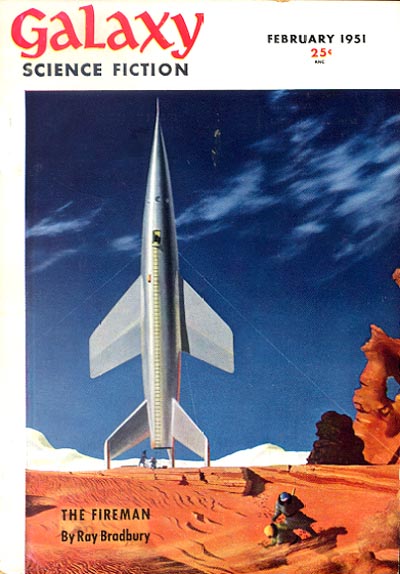

Galaxy, edited by H.L. Gold, emphasized the "soft" sciences such as psychology, sociology and anthropology.

In fact, during the mid-Fifties, most of the science fiction field had veered away from John Campbell's neat and tidy universe and explored, instead, the phenomenologically variable universes that human think they inhabit but in fact might not. Philip K. Dick began his extraordinary writing career during the mid-1950s and was on the forefront of stories that suggested that reality wasn't what we'd been told it was. (The career of Philip K. Dick was beginning at this time and we well end the course with a Philip K. Dick story that underscores this very notion.)

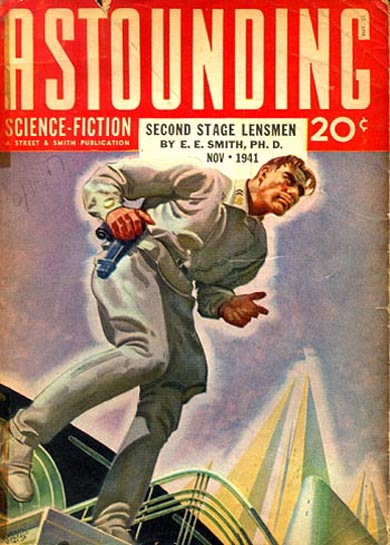

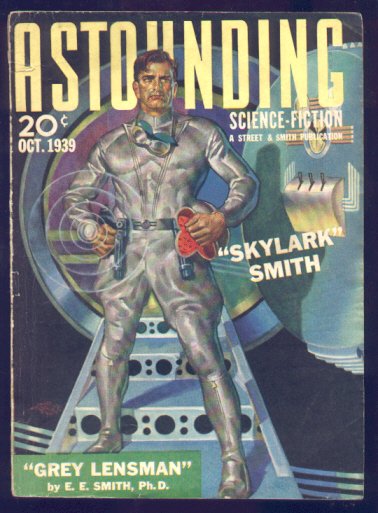

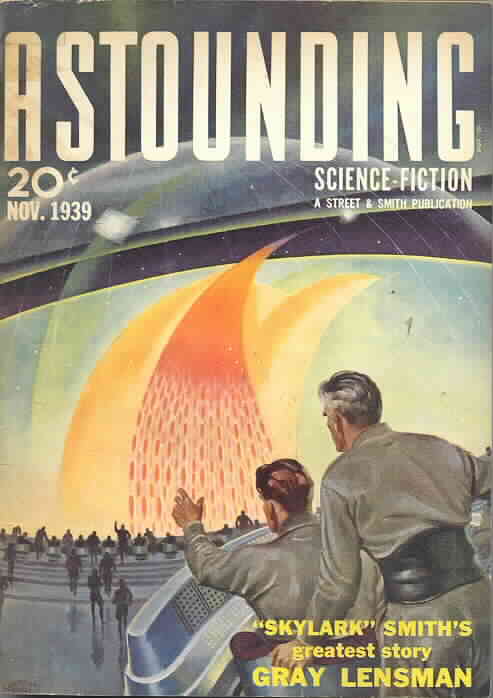

One of the most important science fiction writers to emerge in the 1950s was British writer James Blish. Blish was a thoroughgoing Campbellian most of his life and parts of his major work, his four-novel series called Cities in Flight, were published in Astounding/Analog. Cities in Flight still stands as a major achievement in the field, both as a concept and as a series. In these lectures I haven't really discussed the series either as a publishing phenomenon or as a science fiction and fantasy mainstay. There have been recurring characters in other genres of fiction (Zorro, Sherlock Holmes, Philip Marlowe, James Bond, etc.), but science fiction was the first field of literary endeavor to allow a longer story to evolve through separate novel-length narratives published over a period of years. E. E. "Doc" Smith's "Lensman Series" ranks as the greatest "Space Opera" and Isaac Asimov's "Foundation Trilogy" is known to one and all. Other great series are Frank Herbert's Dune series and Philip Jose Farmer's Riverworld saga.

|

|

|

|---|

E.E. "Doc" Smith was a mainstay of Astounding Science Fiction in the late 1930s through the 1940s. These novels contain the essence of "space opera" and everything George Lucas put in Star Wars can be found in the pages of these wonderful adventure stories that no movie has yet to top.

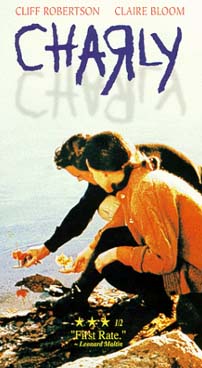

But World War II showed us that the common man could be an uncommon hero, and the 1950s were rife with stories about ordinary people caught up in extraordinary situations. The Sheckley story is one of those, and so too, is Daniel Keyes' heart wrenching "Flowers for Algernon." This is the only story Keyes is known for today, but it's a doozy. The emotional impact of the story comes from its narrative strategy-the diary of a retarded man as he evolves into something of a mental giant. The novella version received a Hugo in 1960 and the novel version in 1966 received the Nebula Award for the best novel of the year. "Flowers for Algernon" was made into the movie, Charly in 1968.

"Flowers for Algernon" is one of the few stories in the field that makes use of a narrative technique rarely employed in the genre. Tales told in journal or epistolary format go all the way back to the 1700s to writers such as Daniel Defoe and Samuel Richardson, later to be used by Poe and Hawthorne. It's a strategy that has its own built-in sense of verisimilitude and we can actually see the changes as they happen to Charly in "Flowers for Algernon." You might also take note here of the similarities to Frankenstein where the monster is allowed to tell part of own tale. "Flowers for Algernon" is one of science fiction's clear masterpieces.

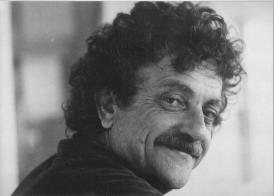

Perhaps the greatest satirist since Mark Twain was Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. Vonnegut's stories have an eerie stylistic simplicity, masking, as it does, a devastatingly sharp wit that has yet to be equaled. Curiously, Vonnegut's "Harrison Bergeron," though written in 1961, seems more relevant to life in 21st America than the early Sixties. Today, it seems, everyone has fallen victim to some form of "political correctness" or another. The 1990s especially saw litigants in courts across the land, claiming one kind of abuse or another at the hands of someone who probably had no idea that they had said or done a thing. It was just the tenor of the times. In fact, to offend anyone for any reason was a no-no in the Eighties and Nineties. "Harrison Bergeron" is a perfect example of the morals of a society out of control; society itself has become the Frankenstein monster.

In an effort to make everyone feel good about themselves (or not to feel bad for what they, in fact, are), we've made it so that anyone who excels is viewed with contempt and eventually censured, especially anyone who's thought a bit deeper about the nature of reality or who might have a more informed opinion or who might have just "gone the extra mile" to become the person they wanted to be, someone exceptional who might embarrass us simply by being around. Imagine what life would be like without them showing us what can be done? Here are two of my favorites.

Madonna Ciccione |

Muhammad Ali |

|---|

* * *

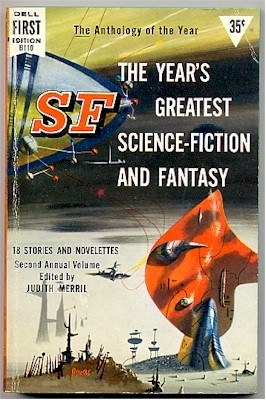

Another important factor in the growth of the science fiction field in the 1950s is the rise of the science fiction anthology, both in paperback and hardbound formats. Anthologies allowed for the greater proliferation of stories that were deemed exceptional for the previous year (or fit a particular editorial format, such as stories about robots, or time travel, etc.). This way, authors were able to earn a little bit more money and keep their names current in the minds of the reading public. However, this was also the era of the superb science fiction editor as well, and important editors were legion. Among them were Martin Greenberg, Damon Knight, August Derlith, Geoff Conklin, Frederick Pohl, the aforementioned Donald Wollheim, then later on the extraordinarily influential Judith Merril whose Year's Best SF routinely contained some of the best reading on any planet.

|

Judith Merril |

These books continued to chip away at John Campbell's influence over the field of science fiction, even if they always contained a story that originally came from Astounding. Campbell nonetheless published excellent science fiction until the day he died.

But the 1960s are now upon us and by the end of the decade, everything will have changed. And I mean everything.