THIRD LECTURE

So far we've tracked science fiction (mostly in America) up to the Second World War. This period is also John W. Campbell Jr.'s halcyon as a distinct influence in the field. Indeed, this influence still persists today and can be found in the "hard science" science fiction of writers such as Gregory Benford, Greg Bear, Stephen Baxter and Arthur C. Clarke. I've also spoken of both Heinlein and Asimov as the quintessential Campbellians of this period. For most of World War II, in fact, Astounding was the place to publish literate science fiction even if all the other SF pulps-Amazing Stories, Planet Stories, Super Science Fiction, Startling Stories, and Thrilling Wonder Stories and a host of others-were all going full tilt.

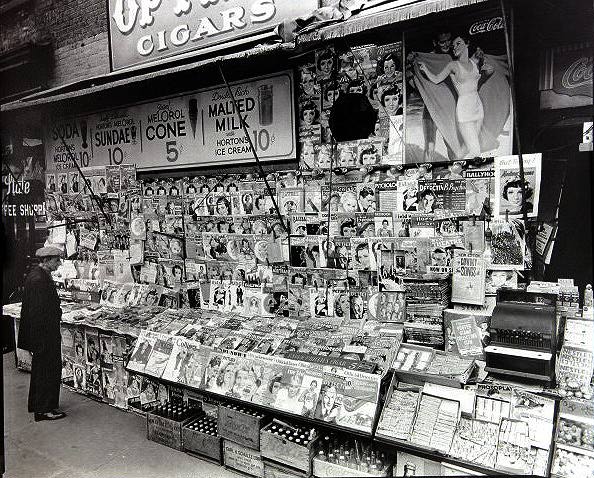

The next few changes to the science fiction genre happened as a direct result of World War II. The first major development was the rise in inflation caused directly by the accelerated pace of wartime needs of the nation. This, in turn, led to a rise in the price of most of the magazines of the era, including the pulps, even if the discretionary income of the average American hadn't kept pace with the rise of the prices of consumer goods. Pulps began to go up a nickel here, a dime there, and by 1946 many pulps were now selling for twenty-five cents where in the mid-Thirties they were selling for ten or twenty cents. And while the war effort employed those Americans who wanted employment (as opposed to those Americans who, during the Great Depression, couldn't find employment no matter how hard they tried), there was even less money in an average household to be spent on recreational reading material. Though radio shows were as popular as ever, movies were beginning their ascendancy as America's favorite form of mass entertainment. And these still remained very affordable. But the dime you'd have earlier spent on a pulp magazine now went to the Saturday morning matinee at the local theater.

Magazines and newspapers also had to face the paper shortages brought about by the war. Print runs of the pulp magazines began to shrink and in 1943, Street and Smith, who published The Shadow, Doc Savage, and Astounding Science Fiction, began publishing their magazines in a smaller, "digest" format (approximately 5 1/2 inches by 7 1/2 inches in size), the size TV Guide is today.

While this was done to help the war effort, it also effected sales, even if other SF pulps did not undergo this same downsizing. Still, many of the most popular pulp magazines of the 1920s and 1930s had finally gone out of print by 1945 (the gangster, aviation and war pulps particularly). Most of the science fiction pulps, however, did stay in print well into the 1950s. Amazing Stories, Future Science Fiction, Thrilling Wonder Stories, and Planet Stories were among the survivors. However, these pulps tended to publish stories of a more garish "comic book" nature than anything else and their covers became more and more campy, trying to appeal to SF's new, young audience. Which brings us to the other factor that helped destroy the pulps: the onset of comic books.

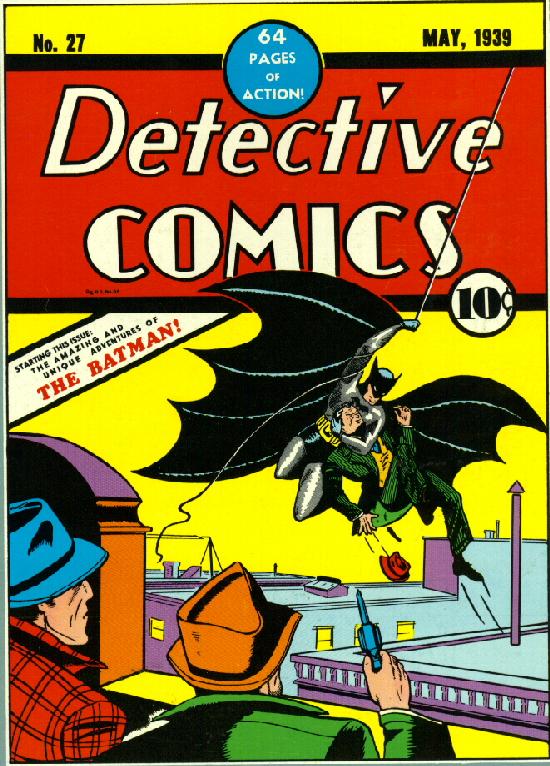

The science fiction pulps had always had a young readership, but much of that readership was forever torn away from the pulps when comic books began publishing the adventures of superhero characters in 1939. Comic books evolved from the "funnies" and were reprints that first appeared in the Sunday papers across the country. A few companies began publishing them alone and in color in the late 1920s. Among these were Jungle Jim, Blondie, Krazy Kat, Polly & Her Pals, Barney Google, Tillie the Toiler, and Little Jimmie. But the "Golden Age" of comics doesn't really begin until Superman and Batman came along toward the end of the Depression.

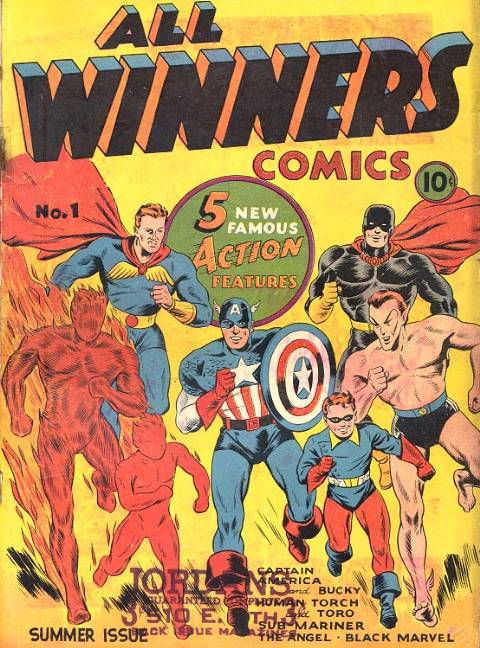

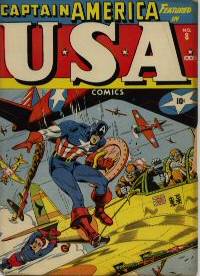

The Marvel Comics line appeared soon thereafter. Marvel Comics started out in the late 1930s as Timely Comics under the helm of Martin Goodman. Employing the talents of a very young Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, Marvel created bizarre science fictional characters such as the android Human Torch, the underwater monarch Prince Namor, the Sub-Mariner, and the scientifically-altered Captain America in the early 1940s.

|

|

These titles, and many more like them, stole both money and readership away from the pulps for as long as World War II lasted (they were also a great source of war propaganda). Comics were also easier to carry, easier to store-and easier to hide from Mom. They also used less paper per issue than pulp magazines, thus were less susceptible to the paper drives that crippled the pulp industry.

By the late 1940s most of the 1000 or so pulp magazines that had been published since the late 1890s had perished. Indeed, the forces of postwar inflation had also crippled the new comic genre. Even though comics--especially those with superheroes--sold in the hundreds of thousands of copies per issue, by the end of the 1940s very few comics had survived the decade. There were just too many of them. In comics, the Golden Age goes from 1938 to 1955. By then, the pulps were long dead and the few superhero comics left were sputtering along sustained only by Superman, Batman, Captain Marvel and Blackhawk. Captain Marvel, however, soon disappeared when National DC sued the publishers of Captain Marvel for copyright infringement. They claimed that Captain Marvel was just a different version of Superman. Ironically, Captain Marvel later reappeared as a member of the DC universe.

As if comics weren't enough of a threat to pulp science fiction, the late 1940s saw the first appearances of paperbacks. Cheap, easy to carry books made entirely of paper (without boards) go all the way back to the Renaissance in Italy. However, after World War II paperbacks became the reading venue of choice for most kinds of fiction, fiction that in just a decade earlier was published in the pages of pulp magazines. The paperback industry also allowed writers who formerly made money by writing fast and furiously for the pulps to branch out into the bigger market of paperbacks and make much more money. (The Beatles satirize this trend in their song "Paperback Writer".) Mainstream writers, such as Hemingway, Faulkner, and John O'Hara--to name just three--could also make a living from books formerly available only in hardbound versions. This also changed the landscape of bookselling itself. Gone were the giant magazine and newspaper stands of the Thirties and Forties and along came actual bookstores. Believe it or not, before 1950, bookstores were isolated affairs. There were no chains and books were mostly sold in department stores. Paperbacks also could be sold in narrow stand-alone racks and began appearing everywhere just about anything was sold.

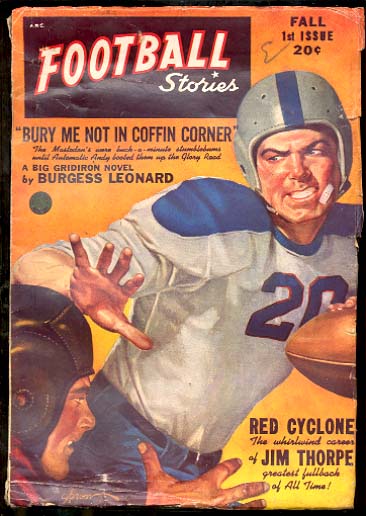

These early paperbacks covered all the genre fiction markets created by the pulps with the only true exception being the sports fiction pulps. The readership for sports fiction virtually evaporated after World War II. Today it's hard to imagine a novel-length story published in Sports Illustrated. In fact most sports fans in this day and age would have no interest whatsoever in reading a magazine filled with sports fiction. But for a short time, readers in the 1930s couldn't get enough of sports action and would take it in any form they could get it. We get our action these days from television and movies. That particular pulp market was killed by television and has never recovered.

|

|

|---|

Dozens of sports pulps that thrived in the 1930s. Sports fiction, beyond the baseball novel, in virtually unheard of in this day and age. It is arguable that the average sports fan, anymore, doesn't have the patience for sports narratives that the common reader in the Great Depression had.

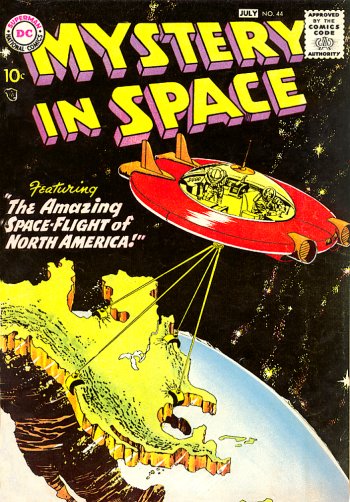

Of course science fiction comics thrived during the early 1950s both at National DC (home of Superman and Batman) and at Marvel (soon to be home of the Fantastic Four and Spiderman). But as readers matured, they had to turn to paperbacks to get their science fiction fix, as only Astounding Science Fiction, Thrilling Wonder Stories and Planet Stories survived into the 1950s.

|

|

|---|

Mystery in Space would soon become home to Adam Strange and Strange Adventures would later publish the first appearances of Deadman, Animal Man, the Atomic Knights and Carmine Infantino's extraordinary "Space Museum" stories.

------------------------------------------------------

|

|

|

|---|

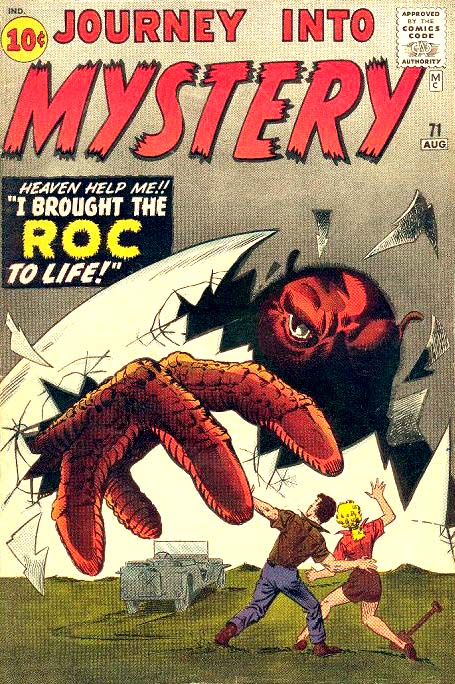

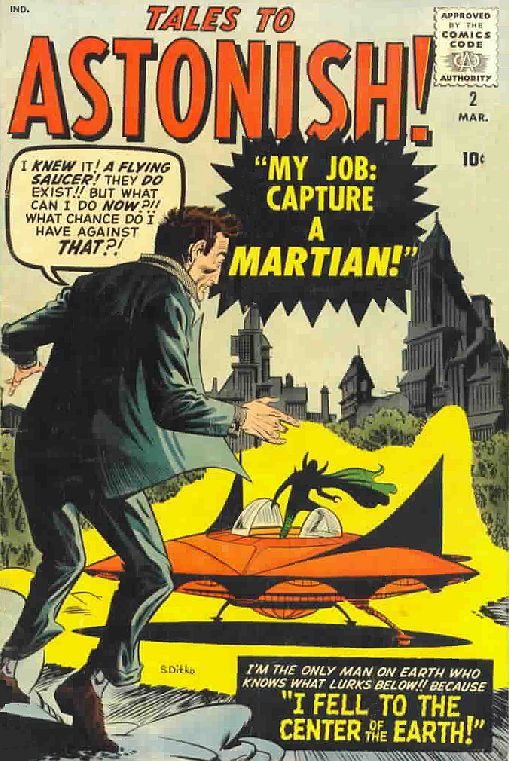

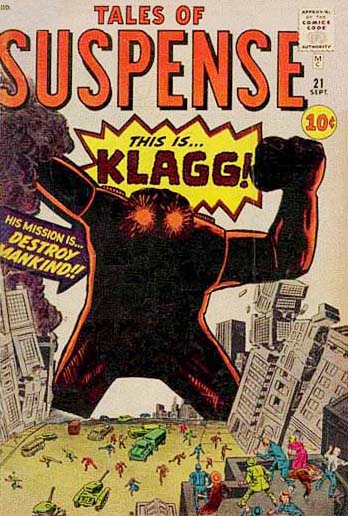

Journey into Mystery would later contain Marvel's first stories featuring Thor. Tales to Astonish would harbor first Ant Man, then Giant Man, then The Wasp and God knows what all. Tales of Suspense is known for its creation of Iron Man, one of Marvel Comic's most enduring characters. As a side note, the covers here all happen to be drawn by Steve Ditko who is now considered to be one of the greatest comic artists who have ever put pen to paper. He and Stan Lee brought Spiderman to life in the mid-Sixties.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

Still, Astounding Science Fiction thrived the rise of the comics and the paperback. One reason for this was that John W. Campbell kept the tone of the magazine serious. Court jesters did emerge in the pages of Astounding-Eric Frank Russell early on and Harry Harrison later on were the best of them-but by and large Campbell kept his whimsical stories to a minimum. The world of the mid- to late-1940s was still a serious place. Satire would come to the field later, but rarely in the pages of Astounding. Campbell was a practical man and the stories he published in Astounding reflected his no-nonsense view of science and the universe at large. Part of this was due to the slow rise of what became known as the Cold War and stories of alien invasion began to take on an East Versus West tenor. Then, once the atomic bomb was developed, the genie of destruction was truly released from its nuclear bottle.

Setting aside the immediate destructive effects of a nuclear war, the aftereffects of residual radiation were only now making themselves known. By 1948 the United States had developed the hydrogen bomb and was actively testing them on land, in the sea, and in the air. With so much residiual Strontium in the air, who wouldn't think there were mutants everywhere?

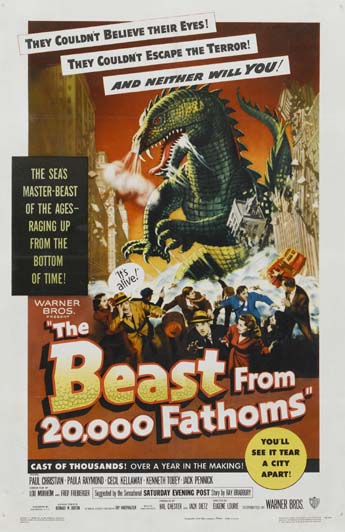

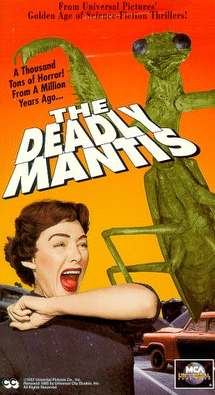

|

|

|

|---|

Movie Posters from the Fifties

The fact was that nuclear radiation was becoming the chief suspect in mutations of all kinds worldwide. Science only had an inkling of this when the Curies discovered radium in 1911. When nuclear testing by both the Soviets and the United States began in earnest in the 1950s, the horrors of residual radiation-which could linger in the ecosystem for centuries if not millennia-were only becoming known. Merril's story, "That Only a Mother" is based on that old saw, "The baby had a face that only a mother could love" and achieves its poignancy in what it has done to the mother. Yet mutants have long been a trope in science fiction with A. E. Van Vogt's Slan, Olaf Stapleton's Odd John and Robert Heinlein's Orphans of the Sky, among the best early SF novels about mutants.

Indeed, the science fiction trope of mutants in general will become important Cold War inventions particularly at Marvel Comics when they create both the Hulk and the X-Men. So while the Cold War might have ended in 1989 or thereabouts, the issue of mutants (or genetic accidents of one kind or another) still is around in our culture and still has relevance. These were the Frankenstein monsters of the Cold War.

.While Astounding plodded along with its same, narrow vision, many of Astounding's former writers found Campbell's influence a bit stifling. Heinlein left, so too did Theodore Sturgeon. Science fiction was changing, developing a more human, social side, sometimes analyzing the inner life of human beings in the future as well as their outer lives.

"It's a Good Life" by Jerome Bixby is the only story that survives from Bixby's fairly prolific career as a writer. But it's a hell of a story and remains as one of the greatest SF stories of all time. Like "That Only a Mother," Bixby's "It's a Good Life" is about an all-powerful mutant boy who makes the world around him-and the adults in it-conform to his wishes. It was also made into one of the most memorable episodes of the original Twilight Zone series. It aired on November 11th, 1961 with Billy Mummy as the special child and scared the hell out of everybody.

"It's a Good Life" also is a perfect story to bring back into play our (my) definition of science fiction: Science fiction is an expression in literature of an author's sense of dread based on perceived or imagined changes in society brought about by science and technology since the time of the Industrial Revolution. Remember? "It's a Good Life" by Jerome Bixby taps into that fear of mutants (and whatever made them that way) so prevalent in the 1950s. What makes the story so horrific is that it's told from the point of view of the helpless adults. It, too, is another Frankenstein story, and a damn good one at that.

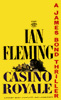

Finally, to conclude this lecture, we have now reached a time in the evolution of science fiction (at least in America) during the 1950s when Campbell's influence as an editor was beginning to wane. Magazines such as Galaxy, If, Amazing and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction all stood to challenge the singular vision of John Campbell. The world at large was now faced with the threat of nuclear annihilation and the Cold War conjured visions of spies and subterfuge and the possibility that governments could fall-particularly our government. This was the era of James Bond (Casino Royale was published in 1953) and the international spy thriller.

|

|

We will have more to say about James Bond in our next lecture.

One of the greatest novels of the 1950s was On the Beach by Australian writer Nevil Shute which appeared in 1957. This book, and the excellent movie made from it, scared everyone silly because everyone alive feared nuclear war. In the novel On The Beach everybody dies from the radioactive residue of a nuclear war that had taken place in the northern hemisphere. And I mean everybody. Had John Campbell been Shute's editor, the book would never have been published or published with a happier ending wherein the few surviving humans go to Mars or live underground or travel thousands of years into the future when the surface of the Earth had healed--something hopeful. Campbell was at heart an optimist. He felt that somebody somewhere would have survived and the race would continue.

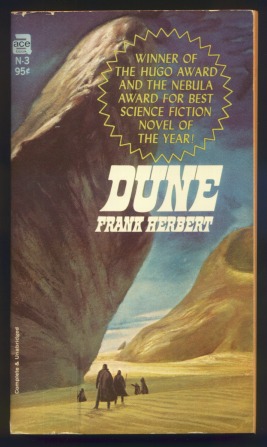

The best is yet to come, however, as science fiction evolves further into realms of political satire and sociological commentary. Even so, Campbell's influence will remain strong. In the late 1950s Astounding will change its name to Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact and Campbell will publish authors such as Anne McCaffery and will serialize one of the greatest SF novels of all time (perhaps the greatest), Frank Herbert's Dune. Science fiction is starting to grow up, its readership is starting to expand and publishers are beginning to take it more seriously.