Deviche Lab Page

Deviche Lab Page

Reproductive Physiology and Behavioral Neuroendocrinology

![]()

Reproductive Physiology and Behavioral Neuroendocrinology

|

|

|

Neuroendocrine Control of Reproduction |

We are investigating the neuroendocrine bases of seasonal changes in reproductive physiology in birds. Most bird species that live at middle and high latitudes reproduce seasonally. In these species, increasing day length in the spring is the primary factor responsible for development of the reproductive system and for the behavioral changes that characterize the breeding season and accompany this development. Prolonged exposure to long days, however, eventually induces photorefractoriness, which is defined as a loss of sensitivity to day length that was previously stimulatory. Photorefractoriness is mediated centrally and causes regression of the reproductive system, but little is known regarding the central processes involved. We focus on the neural bases of photorefractoriness with particular attention to role of the brain peptide, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and its precursor, PrePro-GnRH. We are also studying species that do not follow the typical above pattern of seasonal changes. These include species that can reproduce year-round or nearly so and, may, therefore, not be photoperiodic. Also under investigation are species that breed seasonally, but in which development and regression of the reproductive system appear to be partly or entirely controlled by factors other than day length. This is the case of so-called opportunistic breeders. Opportunistic species often live in unpredictable and extreme environments such as the arctic and deserts and may time breeding as a function of factors such as local food availability or precipitation.

White-winged

Crossbills, Loxia leucoptera, feed primarily on conifer seeds and breed

opportunistically based on the availability of these seeds. We found that circulating levels of reproductive hormones

(testosterone in males; luteinizing hormone and prolactin in both sexes) at a given time of the

year vary from one year to the other. These variations correlate with local food

availability, but apparently not with changes in ambient day length.

Listen to White-winged Crossbill song.

The Rufous-winged Sparrow, Aimophila carpalis, is a resident species of the Sonoran desert. This species breeds opportunistically in response to summer rains. Little information is available on the reproductive endocrinology of this species and other desert birds. We are investigating the neuroendocrine bases and the ecophysiology of reproduction of Rufous-winged Sparrows using a combined field and laboratory approach.

Listen to Rufous-winged Sparrow song.

Gonadotropin-releasing

hormone (=GnRH I)-producing cells are localized in the preoptic area of the brain

(House Sparrow, Passer domesticus). Seasonal changes in GnRH production and secretion play a pivotal

role in the control of the activity of the reproductive system. We are analyzing these

changes and their basis in species that

time breeding based primarily on seasonal changes in day length or on other environmental

factors.

Gonadotropin-releasing

hormone (=GnRH I)-producing cells are localized in the preoptic area of the brain

(House Sparrow, Passer domesticus). Seasonal changes in GnRH production and secretion play a pivotal

role in the control of the activity of the reproductive system. We are analyzing these

changes and their basis in species that

time breeding based primarily on seasonal changes in day length or on other environmental

factors.

Neural Plasticity and its Relationship to Behavior |

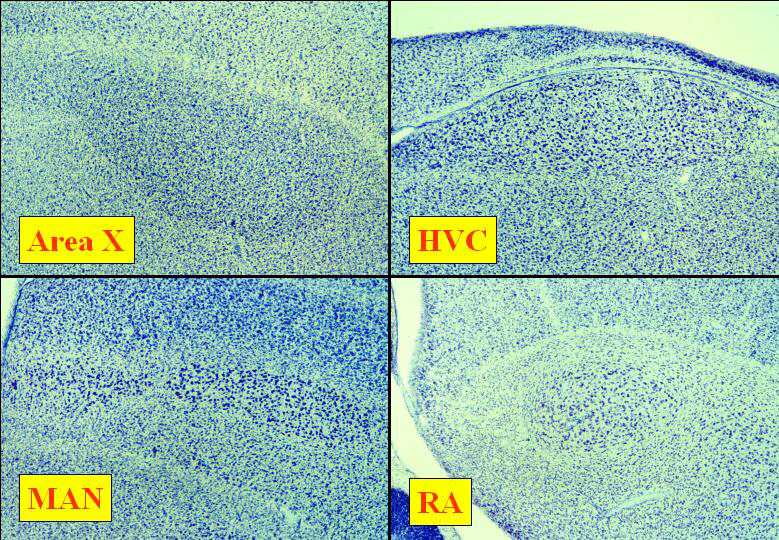

Seasonal reproductive system development and regression concur with profound behavioral changes. For example, in many avian species song is expressed seasonally. This behavior is also often sexually dimorphic. During the breeding season it is gonadal hormone-dependent, and it is controlled by specific and interconnected brain regions. Some of these regions retain considerable neural plasticity in adulthood in that new cells are added and eliminated throughout life. As a result, the sizes of some brain regions involved in vocal control change seasonally concurrent with changes in vocal behavior expression. We are using a multi-disciplinary approach to elucidate the relationships between gonadal hormones, vocal behavior, and its neuroanatomical substrate. We are also interested in elucidating the cellular mechanisms of action of gonadal hormone on vocal control regions.

Vocal behavior learning and

expression are controlled by brain regions including those shown on

these photographs (adult male Dark-eyed Junco, Junco hyemalis).

These regions are sensitive to gonadal hormones during ontogeny and in

adulthood. In many species the same regions are present in females, but are smaller in these females than in conspecific males. We are investigating the behavioral

functions of song control regions in adult female songbirds and the hormonal

control of these region sizes and neural attributes.

Vocal behavior learning and

expression are controlled by brain regions including those shown on

these photographs (adult male Dark-eyed Junco, Junco hyemalis).

These regions are sensitive to gonadal hormones during ontogeny and in

adulthood. In many species the same regions are present in females, but are smaller in these females than in conspecific males. We are investigating the behavioral

functions of song control regions in adult female songbirds and the hormonal

control of these region sizes and neural attributes.

Hormonal Bases of Blood Parasite Infection and Resistance |

We are researching the hormonal bases of avian blood parasite infection susceptibility. There is evidence that gonadal steroids have complex effects on the immune system. Seasonal changes in plasma concentrations of these steroids in birds are often dramatic and may regulate immune system-mediated resistance to insect-transmitted parasites or the relapse of pre-existing infections, possibly altering survival and reproductive success. We integrate field and laboratory studies to address these possibilities and to understand the mechanisms underlying seasonal changes in insect-transmitted parasite resistance.

Four types of blood parasites are commonly found in passerine birds. Recent evidence suggests that prevalence of and intensity of infection with some of these parasites may be regulated hormonally. Our research investigates the mechanisms that control this regulation.

Our research has been supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.