|

|

|

Crossing The Valley

Paul, citizen of the World You canít judge a book by its cover. You mostly canít tell by looking at immigrants where they come from, what theyíre made of, and what extraordinary tales they have to tell. The Muslim bagging your groceries may be but a humble, honest Kurdish man displaced by genocide between Americaís gulf wars. A southern Vietnamese factory worker I work beside was a physician in his homeland. After the fall of Saigon he spent 5 years in a prison camp and later found refuge in America, and steady work as a laborer. One Mexican man serving you lattes at a local cafť is far more than he seems. You may not even know heís from Mexico at all as his English is fluent and his features not so dark. Your might think this is another typical story of a Mexican illegally coming into America to seek a better life and landing in the service sector. Think again. This world is much too complex, varied, and colorful for such generalities. Everybody has a story to tell. The following is Paulís brave and uncommon narrative. ďI just want a few more minutes sleep!Ē Paul exclaims. High school can be such a drag. At least Iíll see my friends there I think. Itís March and spring is in the air in CuliacŠn, Mexico. Mind you I like high school and my exam grades are good. I even took some high school classes for college credit. I plan to attend the Uni to become a dentist. Itís getting up early that I hate! Soon high school will be over and friends will go their separate ways. But for now my friends and family are all here close to me.

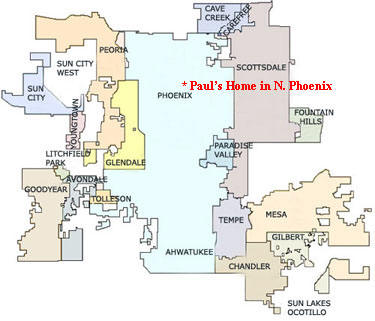

I have many relatives around the CuliacŠn area. Aunts, Uncles, cousinsÖ..I also have an Aunt and Uncle living in Phoenix, Arizona. They migrated in 1984 or 1985 and were able to get citizenship in the 1986 Amnesty. One of my uncleís here in Mexico is a prominent prosecutor. He was even involved in sending members of a local drug cartel to prison. Heís pretty much a hero, no matter how you slice it. This proved to be tragic for my family although. Donít get me wrong, Iím proud of my uncle, but the cartel vowed to get even. Within a month my uncle and his son, my cousin, were dead. While at the memorial service my family found out that two of my other cousins had been murdered! While I still had the chance, I had to leave. I had to leave just to live! I didnít want to leave my family and friends. I didnít want to leave everything that I knew. But there is no security in Mexico, the government is no help. They canít protect you. Nowhere was safe for me in Mexico. On April 19, 2000 I left by car with a relative bound for my aunt and uncleís house in Arizona. The passage was the unremarkable part of my story. We simply drove to my aunt and uncleís house in Phoenix. Getting a fake Social Security card is easy if you know how to find one. There was this 99 cent store in central Phoenix in what has become a mainly Mexican immigrant neighborhood. You give the person about $150 and they give you a Social Security card with made up names and numbers, under the table of course. Those papers became invalid after Proposition 200 passed in Arizona and my work checked out my Social Security number. At this point my boss, an American citizen, said he had encountered another employee with this problem and put me into contact with this guy. I ended up in a scary neighborhood in south Phoenix in a run down house and got a false Social Security number with "valid" information. The card looked exactly like a government issue and it should have; it cost nearly $400 and that was a long time ago now. It looked like the cards were made in-house and definitely was a place you would only want to visit once in your life. I figure the money I in payroll deductions just stays with the government? Finding a job and making a living is easy here in Phoenix. Missing home is the hard part. I donít want to be here, but where else do I turn? My contact with my family is very limited. I only talked with my Mom and two of my cousinís back home. Thatís it. Usually I worked one job in the service sector and also attended classes, first at Rio Salado Community College in Phoenix, then Paradise Valley Community College after that. At times Iíve also worked two jobs at the same time, both service jobs. Unlike manufacturing sector jobs that could be outsourced to exploit cheaper labor abroad, service sector jobs cannot easily be sent overseas. Businesses have had to exploit a cheap labor force closer to home for these service jobs, mainly Mexican immigrants (Janitors, Street Vendors, &Activists: The Lives of Mexican Immigrants in Silicon Valley by Christian Zlolniski, 2006). It was very difficult and lonely for me here at first. The language barrier was the biggest problem especially at work. I didnít know how to do anything and no one showed me how I should do things. I wish there was a manual in Spanish they couldíve given me. That wouldíve been a godsend! I learned English by taking ESL classes in college and also by the total immersion of living with my relatives (my cousinís were born in America and mostly speak English). Sometimes the language barrier makes for some funny situations. When I first started working at a bagel shop, a woman asked where the bathroom was. I didnít know what she said so I just answered ďyesĒ. Finally she had to make a gesture like she was pulling down her pants and squatting. Thatís when I got the message. I never have really encountered any cultural misunderstandings here. Life here isnít so different after all. I have felt discrimination though. I was in a restaurant five years ago and needed a to go box for my leftovers. I asked a man who ended up being the manager for a to go box and he got mad at me for no reason! He said that I canít have a to go box and then said in Spanish ďleave and donít come backĒ. Obviously that made me feel really bad. Usually everything is good here though, except for missing home so much. One time I had to find parts for my car and had to go into southwest Phoenix. Iíve never been in such a scary neighborhood! I never want to go back there again! I think my most memorable events since Iíve been here in Phoenix have been going to concerts. They are cheap here and these artists would never come to CuliacŠn. The restaurants are also awesome. We went to the Phoenician before a concert one time. It was very cool. Iíve heard that the guys my uncle sent to prison are dead now. I hear that the cartel has disbanded. I think that the vendetta against my family may be over. If it is I can return home to Mexico soon to be near my friends and family. Iím going to wait around ten months to see if the coast is clear. If nothing happens between now and then I will return home. Many friends back home are gone now. Life takes people different places. Through immense tragedy, I ended up on an adventure that I never wanted to take. This experience in America has given me a broader perspective on the world and for this I am better. This last line isnít exactly how Paul said it. He wanted to say itís made him better, but didnít want to sound so presumptuous as to call himself ďbetterĒ. I hope Paul can safely return home someday but not because I want to see him go. America will have lost a good citizen.

State of Sinaloa, Mexico Although remittances play a vital role in many Mexicanís migration stories, thatís not the case in Paulís story. He would send money or gifts home for Christmas, birthdays, and other special days which I just canít categorize as remittances. Most people living far from home do these things if they can. In the 1992 study by Schiller et al, Transnationalism: A New Analytic Framework for Understanding Migration, transnationalism is defined as a process by which immigrants build social fields that link together their country of origin and their country of settlement. Paulís lives a transnational life as much as possible considering the dramatic circumstances of his departure. His heart is in CuliacŠn and he longs to return home to friends and family. He also wants to move on with his life and to not be left in limbo any longer here in America. His return fits with the transnational model of migration that asserts that Mexico-U.S. migration has historically been circular. In Dr. Douglas Masseyís 2005 article Five Myths About Immigration: Common Misconceptions Underlying U.S. Border-Enforcement Policy he states ďAccording to estimates by a variety of researchers, the annual probability of return migration (to Mexico) was around 33% through the early 1990ís. Paul, like many other Mexican immigrants, dream of returning to the community and family that they left behind. In 2001 Saskia Sassen illustrated the fact the city is a place where global economic forces often collide. Sassen asserts that the global city is a place of an unprecedented widening between haves and have nots and of a devaluing of necessary jobs. He also highlights that the city is a place where the have nots do have visibility and political power. He wrote ďI think we have arrived at a point (in global cities) where a new politics is called for. And thatís where I see the fit of a lot of particular actions, initiatives and social movements. For me, these kinds of cities contain within them the strategic structures that valorize global capital, but also the strategic conditions for the valorization of the political power that these disadvantaged people represent.Ē It seems that Sassenís intellect borders on the prescient in light of todayís unprecedented and massive immigration demonstrations in cities across the U.S. The powerful arenít the only oneís who can find avenues to better their situation. Phoenix is one of those global cities and Paul one global citizen who, like the rest of us, are trying to find his way in a world where far off and powerful forces beyond ones sphere of influence shape and re-shape the political and economic landscape. |

|

CuliacŠn

is the largest city in the state of Sinaloa as well as its capital.

Itís the fifteenth largest city in Mexico with nearly 750,000

inhabitants. In the 1950ís the federal government built dams in the

area and agriculture industry exploded and the town grew

exponentially. Per capita income is only ľ that of the U.S.

Unemployment in the region is a low 3% but they are generally low

skilled jobs in agriculture, ranching, and tourism

CuliacŠn

is the largest city in the state of Sinaloa as well as its capital.

Itís the fifteenth largest city in Mexico with nearly 750,000

inhabitants. In the 1950ís the federal government built dams in the

area and agriculture industry exploded and the town grew

exponentially. Per capita income is only ľ that of the U.S.

Unemployment in the region is a low 3% but they are generally low

skilled jobs in agriculture, ranching, and tourism