|

Home

Field Research

Current Projects

Publications

Databases

|

Current Projects |

|

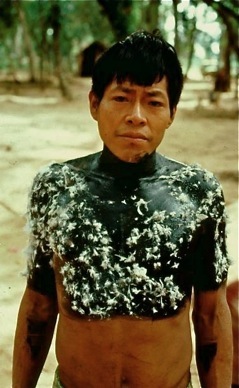

My fieldwork emphasizes hunter-gatherer populations of the Neotropics, and the behavioral ecology of small scale tribal peoples in Latin America. I have worked since 1977 with the Ache hunter-gatherers of Paraguay. In addition I carried out fieldwork with Hiwi hunter-gatherers of Venezuela, and the Mascho Piro, Matsiguenga and Yora populations of Manu Park Peru. I have visited dozens of indigenous communities throughout Latin America.

|

The origins of human uniqueness: Culture and Cooperation |

Health challenges, cooperation, and the human life history. |

Evolution of the human life history. |

Cultural Ecology of Modern Hunter-Gatherers. |

The origins of human uniqueness: Culture and CooperationA growing number of social scientists and biologists have become comfortable with the explicit recognition that humans are animals that have evolved like others, and whose behavior ultimately can be explained by cognitive mechanisms that were crafted by natural selection. Humans are not exempt from the adaptive processes that account for the diversity of life on this planet. Nevertheless humans are notably unique among the forms of life on earth. This uniqueness can be detected in the overwhelming dominance of our species as it rapidly replaces myriads of others, and the amazing complexity of human society and technology that transforms the planet at a magnitude not approached by any other species. We propose that human uniqueness is the product of extraordinary cooperation that was derived from a pre-adaptation of cooperative breeding, in conjunction with the social transmission of cultural conventions that promote “other-regarding behaviors” between non-kin in a way not seen in other animals. These traits (and the underlying physiological and cognitive machinery that produces them) appear to have coevolved and may explain the expansion of a small population of Homo sapiens within Africa during the later Pleistocene, and the ultimate replacement of alternative forms of Homo throughout the world. Furthermore, the emergence of this exceptional cooperation probably coincides with the origins of morality and ethnicity, and the unique emotional underpinnings of these phenomena that make us human. The suite of characters that make our species both successful and unique appear to implicate natural selection of both genes and cultural patterns at levels, from the individual, to large cooperative-breeding extended-kin-units, and probably to higher level coalitions of individuals and extended-kin-units with shared cultural patterns. If so they represent a fascinating new area of biological/social research the may account for the characteristics of our shared humanity.read a description of the “origins of human uniqueness” project at this link

Health challenges, cooperation, and the human life history.This project is based on a novel understanding of human evolution that connects cooperative solutions to health challenges during late Hominin history to the evolution of the major traits that make our species unique (cognition, cooperation, culture) and to the spread of the new species, Homo sapiens, around the globe in the late Pleistocene. The evolved cooperative solutions allowed greatly increased survival through bouts of disease, trauma and other serious health insults. This in turn lowered adult mortality significantly leading to the evolution of a new life history characterized by a long juvenile learning period and exceptional adult lifespan with increased investment in immune function. Thus, we view the human life history, unique cognitive abilities, cooperation and culture as all ultimately related to health challenges. We further propose that, the initial cooperative solutions to hominin health pressures have set the stage for additional adaptive changes in our species. Social networks that have emerged due to human cooperation are now critical for understanding both the spread of infectious pathogens, and the spread of information and health practices needed to combat them. Attaining optimal health around the world (and particularly in small-scale societies) in the modern context requires the solution of multiple collective action (public ) problems, but the likelihood of attaining such solutions is strongly impacted by cultural and cooperative patterns specific to each society. Thus, in short, we propose to study how problems led to the evolution of cooperative tendencies in Homo sapiens, and how currently the ability to tap those cooperative tendencies, and the structuring of social interactions due to them, constitutes the major factor in solving health problems in small-scale communities and in the world.Evolution of the human life history.Humans have an exceptionally long adult lifespan compared to other great apes, associated with a long period of juvenile dependency, low juvenile growth rates, a marked adolescent growth spurt, late age of sexual maturity, extremely high female fertility which terminates long before the end of the expected adult lifespan. These traits are associated with high paternal investment in offspring, resource flows within and between kin groups that subsidize female fertility patterns and constitute a pattern of “obligatory cooperative breeding”. The long adult lifespan and juvenile learning period coevolved with an exceptionally large brain, and a feeding niche shift to extractive and hunted foods. The production of these nutrient rich but high variance resources led to food sharing which lowered mortality due to random incidents of trauma and disease, res ulting in an evolutionary shift to later senescence. The lifespan also coevolved with an increasing tendency to engage in learning intensive foraging which would only be possible with an extensive adult productive period that repays the net energy loss experienced during the learning period. Hence cooperative breeding in the form of menopause, and food transfers from more productive age classes (and sexes) to those of lower net production.Cultural Ecology of Modern Hunter-Gatherers.Modern hunter-gatherers (foraging people) show great worldwide variation in subsistence patterns and social behavior. There is a much greater range of variation present in the archeological record covering world populations after the last glacial maximum. In the project I compose a synthetic overview of the range of patterns described for Holocene foragers, and then assess both universal tendencies and explanations for variation. This information is used to understand the adaptive responses of our recent ancestors and to evaluate patterns of behavior that may have characterized our ancestors in the genus Homo. Late Pleistocene foragers that may represent the first true “humans” with “modern” behavior, are particularly of interest.monograph in preparation “Hunter-gatherers of the world”. |