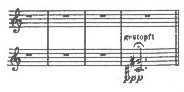

J. R. Lewy and Early Works of WagnerThe beginning of a longer article on the important German valved hornist J. R. Lewy and his career, 1837-51, with the following two articles completing the picture of the connections between Lewy and the horn writing of Wagner. John EricsonThis article is based on materials published in The Horn Call Annual 9 (1997). Some preliminary research on this topic also appeared in The Horn Call Annual 4 (1992). The period after 1835 saw the beginning of the use of the valved horn in the orchestra. Composers and hornists alike were just beginning to grasp the true potential and character of the valved horn. With respect to understanding this important period in the development of the technique of the valved horn, hornist J. R. Lewy is of considerable importance. The article on the topic of Schubert and the Lewy Brothers discussed the first portion of his performing career; this article continues the story, with particular attention given to his unique and frequently noted technique of using the valves as crook changes [see the original version of this article in The Horn Call Annual 9 (1997) for a complete discussion of this final topic]. J. R. Lewy was born in Nancy and studied the horn with his brother. From 1819 until 1822 J. R. Lewy was a member of the court orchestra in Stuttgart, and in 1822 he joined his brother in the orchestra of the Kärntnertor Theater in Vienna [Morley-Pegge, 163]. In the years 1834-1835 J. R. Lewy went on concert tours to Russia, Sweden, Germany, England, and Switzerland [Fetis, 294. Toeplitz, 75, reports that J. R. Lewy was even briefly music director to the Swedish navy in 1835]. He spent the winter of 1836-37 in Paris [Fetis, ibid], and from there Lewy went on to Dresden, where he became principal horn in the Royale Kapelle, performing on the valved horn [AmZ 46, col. 908]. He remained in Dresden from 1837 until his retirement in 1851. It was in this last period of his career that the name of J. R. Lewy became associated with the name of Richard Wagner. The association of these two artists began, at the latest, in early 1842, in the period when Rienzi was being prepared for its premiere in Dresden. J. R. Lewy met with Wagner in Paris in January of that year; Wagner mentioned this meeting in a letter to Ferdinand Heine in Dresden. Herr Lewy, who has been in Paris for the last week & who will probably be leaving us today, spoke of Reissiger, his opera [Adele de Foix] & so on most respectfully & favourably;--but yesterday--as it seemed (--& as I flatter myself--) on a friendly impulse he recommended that I treat Reissiger with great circumspection:--without wishing to be too personal, he said he felt obligated to consider Reissiger weak-willed & lacking any firmness of character:--he warned me & recommended most insistently that I should go to Dresden sooner rather than later, in order to be present & see for myself. It goes without saying that I shall come to the performance of my opera & in any event shall arrive about a week early . . . .[Spencer & Millington, 84-85. Wagner arrived in Dresden on April 12, 1842]. The premiere of Rienzi, which occurred on October 20, 1842, was a great success, and was quickly followed by the premiere of Der fliegende Höllander on January 2, 1843. On these premiere performances J. R. Lewy played the first valved horn part. Both of these works were scored for a section of two valved and two natural horns. While composed in Paris and undoubtedly reflecting elements of French valved horn technique [see the related articles on the topics of Joseph Meifred and the Early Valved Horn in France and The First Orchestral Use of the Valved Horn: La Juive], the horn writing seen in Der fliegende Höllander is nevertheless highly worthy of study in relation to early German valved horn technique. The revised version of Der fliegende Höllander dates to 1846 (with additional revisions in 1852 and 1860) and reflects Wagner's years of practical experience as conductor in Dresden and contact with German valved hornists. [NOTE: Several sources state that Wagner was Hofkapellmeister in Dresden (for example, Morley-Pegge, 2nd ed., 163,) but this is in error; K. G. Reissiger (1798-1859) instead held this position. For more on Reissiger see K. G. Reissiger on the Valved Horn--1837]. The orchestration calls for a pair of valved horns crooked in the keys of F, G, and A, and a pair of natural horns crooked in the keys of B-flat basso, H (B-natural), C, D, E-flat, E, and A. The overture opens as follows, for valved horns in F and natural horns in D. Wagner, Der fliegende Holländer, overture, mm. 1-46. The distinctly contrasting writing for the valved and natural horns in this passage shows that Wagner saw a major advantage in the new instrument. Wagner used the valved horns in F to play a number of pitches not possible to perform as open pitches on the natural horns in D. There is nothing to suggest that he wished the pitches in the valved horn parts to be performed in any manner other than as open pitches using the valves; a definite concern for projection is obvious from the orchestration. While the F crook is called for the most frequently, Wagner does request other, higher crooks of the valved horns as well. The following is an example from Act II for the first horn crooked in A and the third horn crooked in E. Wagner, Der fliegende Holländer, Act II, no. 6, Finale, p. 254. The reason for using this higher crook may well reflect the higher tessitura of this passage. While it was possible to perform all the notes on the F crook, the A crook was requested for improved accuracy, and possibly to make the passage look lower, visually, as well--Wagner likely felt that because the notes looked lower they should be more playable. Wagner allowed time for quick changes of crooks to be made, and it would appear that he intended the valved horns to use all of the requested crooks. As Meifred noted in his Méthode, "It will always be better, in the interest of execution, to use the crook indicated by the Composer . . . "[Meifred, 71, trans in Snedeker diss]. The crooks which Wagner called for on the valved horn are generally consistent with those suggested by Berlioz in his Grand Traite d'Instrumentation et d'Orchestration Modernes (1843) [p. 143--see the related article Berlioz on the Valved Horn], and could be applied to many valved horns of the period. While writing for valved horns in crooks other than F may have initially been a reflection of what French orchestral players were doing in this period (as in Halévy's opera La Juive), Wagner's maintaining these crooks through later revisions must certainly reflect early German practices as well. [NOTE: The opera La Juive is known to have been a significant influence upon Richard Wagner [Westernhagen]. Wagner himself commented favorably on the work in a review of a production of Halévy's later opera La reine de Chypre (1841) [Snedeker, 11-12--see the related article on the topic of The First Orchestral Use of the Valved Horn: La Juive]. One final passage from this work should be examined with a view to stopped horn notations. An unusual notation is first found in the following passage at the end of Act III, no. 7, in the natural horn parts in H (B-natural). Wagner, Der fliegende Holländer, Act III, no. 7, conclusion. This notation is seen two more times in Act III, no. 8: measure 166 in the natural horn parts and again in measure 247 in the valved horn parts. The first of these additional examples is in C and the second is in F, but all three examples request the same written pitches. Wagner placed this marking in these horn parts to confirm that these pitches, if performed on a valved horn, were specifically written where they were to be performed stopped with the hand. [NOTE: Hector Berlioz was also quite clear on this topic. See the related article Berlioz on the Valved Horn]. The valved horn writing in general is reasonable and clear, and from his background J. R. Lewy certainly would have had no difficultly in performing these early valved horn parts of Wagner exactly as written using the originally requested crooks and standard fingerings. SOURCES Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 46 (November 13, 1839), col. 908. [This notice described J. R. Lewy as being the "brother of the famous Viennese horn virtuoso" (E. C. Lewy)]. Hector Berlioz, A Treatise on Modern Instrumentation, trans. Mary Cowden Clarke (London: Novello, n.d.). F. J. Fétis, Biographie Universelle des Musiciens, 2nd ed. (Paris: 1874; reprint Bruxellex: Culture et Civilisation, 1963), vol 5, 294. Joseph Meifred, Méthode pour le Cor Chromatique, ou à Pistons (Paris: S. Richault, 1840), 71, trans. Snedeker, diss, 239. R. Morley-Pegge, The French Horn, 2nd ed. (London: Ernest Benn Ltd., 1973). Jeffrey Snedeker, "The Early Valved Horn and Its Proponents in Paris 1826-1840," The Horn Call Annual 6, (1994), 6-17; the cited passage makes reference to Richard Wagner, Richard Wagner's Prose Works, trans. William Ashton Ellis (London: Kegan Paul, 1898; reprint, New York: Brode Brothers, 1966), vol. IV, 220-221. Stewart Spencer and Barry Millington, Selected Letters of Richard Wagner, trans. Stewart Spencer and Barry Millington (New York: W. W. Norton, 1987). Uri Toeplitz, "The Two Brothers Lewy," The Horn Call 11, no. 1 (October, 1980), 75-76. Richard Wagner, The Flying Dutchman, ed. Felix Weingartner (Berlin: Adolph Fürstner, [ca. 1896]; reprint, New York: Dover, 1988). Curt von Westernhagen, "Wagner, Richard," The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Stanley Sadie, ed. (London: Macmillan Press Ltd., 1980), vol. 20, 105. Copyright John Ericson. All rights reserved. |