It was summer, and a time when I thought everyone

was supposed to be happy and carefree. And in my own little world, I was.

I lived in an isolated world where things were fun and exciting, and no one

was unhappy or afraid. Looking back, I realize that my childhood was the

ideal that we all strive to attain for our own children.

It was summer, and a time when I thought everyone

was supposed to be happy and carefree. And in my own little world, I was.

I lived in an isolated world where things were fun and exciting, and no one

was unhappy or afraid. Looking back, I realize that my childhood was the

ideal that we all strive to attain for our own children.

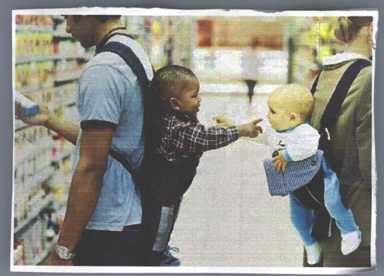

For as long as I could remember, my neighbors, Walt and Mildred W., had provided a home for foster children. The summer of 1970 was no different, except that they had two babies with them that year - Annette, or “Nini” as we used to call her, and Lori. Nini was three years old, had chocolate brown eyes, dark skin, and was mentally handicapped. Lori, also three, was a blonde, blue eyed beauty, who was also, I realize in hindsight, most likely mentally challenged.

Walt and Mildred eventually decided to adopt both of these little girls, to raise them as their own. They submitted the paperwork , the social workers gave their approval. But for the court appearance and the final official seal of approval, everything was in place to bring this little family together. Then it happened. I discovered for the first time the contrariness of a world in which people of color are treated differently.

Walt and Mildred came home from the court appearance with their new daughter. That’s right - daughter singular, not plural. The judge had decreed that although Mildred herself was a blonde, with brown eyes, with Walt’s dark complexion, Lori was “too white” to be placed with them on a permanent basis, but Nini would be a “more acceptable” child for them. And so, Lori, the little girl who had lived with them almost from the day she was born, the little girl they loved enough to want to make a permanent place for in their lives, was removed from their home and placed back into foster care.

I can remember Mildred sitting in our living room, crying with my mother over her lost child. It confused and angered me that they were not allowed to keep a little girl that until that moment, I had thought was their daughter. It was always my thought that Nini looked like Walt and Lori looked like Mildred, just as I look like my Dad and my sister looks like my Mom. It didn’t matter to me that Walt’s skin was darker than Lori’s - she was their little girl and that was what I knew.

It’s funny though - when I think back on Walt’s reaction, I don’t recall that he was ever sad. He always had a smile on his face, even in those dark days. His attitude seemed to be a “What are you going to do?” reflection - as though he had heard it all before and didn’t really expect anything to be different.

Contrary to Mildred’s sadness and Walt‘s acceptance, was my Grandmollie’s perpetual sneer. She was there taking care of my mother after my mother’s recent surgery and could not resist adding her opinion on the situation. I can clearly remember her saying, “Well what is the matter with that? That judge knew better than to allow a white girl to live with a coon and his wife. What would people say?” And for the first time ever, my mother lost her temper with her mother in law and advised her that we do not say such things in her home and that we are all God’s children no matter what color we may happen to be on the outside.

My neighbor’s experience and my mother’s argument with my Grandmollie burst the cocoon I had been living in. For the first time, I started paying attention to things outside my own little world. This incident brought to my attention that people had different skin tones. And that not everyone accepted those differences or considered them as equal. I started noticing that when my parents watched the news, they were horrified at the reports presented of race riots and assassinations. Their concerns about racial injustice represented a vast contradiction to my Grandmollie’s opinions.

Back at school that year, I noticed even more things. Rodney was the only student in my class that had dark skin. My friend Lydia was the only student from the previous school year that had dark skin. Before that summer, it wasn’t something that I had paid particular attention to - or even considered to be of any significance. They were my friends - nothing more. The only reason that I had taken previous note that Rodney was “different” was that in the third grade he did not have to stand up for the Pledge of Allegiance. When I was told it was because of a religious belief, I did not think any more of it. My own religion had different beliefs and this was something I understood.

Until my Grandmollie left for her home in California, just after school started, my home was a bit like a battleground. My mother would be talking about accepting people for who and what they are, while my Grandmollie would be touting the exact opposite - “Nothing good will ever come from mixing white and dark.” Perhaps this incident is still so vivid to me because it brought home the fact that my mother, whom I worshiped, and my Grandmollie, whom I equally adored, did not see eye to eye on these issues. Whose opinion and example should I follow? While I strive to follow my mother’s example, I must confess that every once in awhile, Grandmollie’s words drift to the forefront of my thoughts and opinions.

Until Mildred came over to speak with my mother

about her lost child, I had no idea anyone else or anything else existed outside

of my cocoon. It was the first time that I thought of Mildred as more that

just “the lady next door.” And it was the first time that the world

that had kept me sheltered and protected had suddenly become harsh and cruel.