GENERAL INTRODUCTION TO SCIENCE FICTION

The Three Eras of Science Fiction

The

First Era:

Early Science Fiction

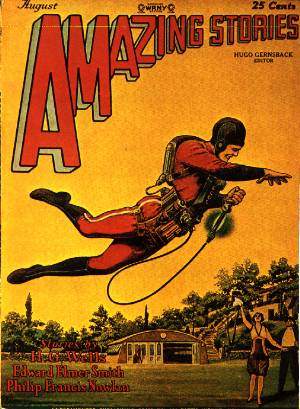

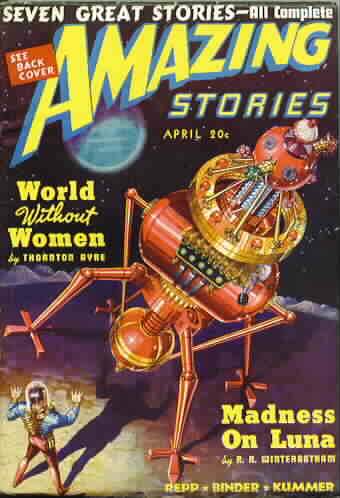

According to Brian Aldiss in his book Trillion Year Spree (Atheneum, 1986) science fiction is an offshoot of the Gothic tale and begins with Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, published in 1818. Aldiss, however, doesn't break down science fiction into the three distinct eras as I am going to do in this course. I suggest that there is a distinctive kind of science fiction that stretches from from Mary Shelley to gadgeteer Hugo Gernsback who will begin publishing Amazing Stories in 1926.

|

|

|

|---|

In the early 1930s, Gernsback will come up with the term "science fiction" (preferring it over the awkward "scienti-fiction," his earlier term) regarding the "new" literature he was publishing. This first era is over a century long and writers such as Edgar Allen Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Mark Twain, and Jack London, to name but a few, wrote stories that were recognizably science fiction. But instead of reading short fiction by the above-mentioned writers, I have chosen for this course several novels to guide us through science fictions many forms.

Three of the novels in this class are designed to show how the genre evolved up through and including the career of H. G. Wells. Two novels are also added that fall into the "scientific romance" subgenre, novels that came out when Hugo Gernsback was starting his publishing empire. In fact, Hugo Gernsback once described science fiction (as he envisioned it) as literature written in the mode of Edgar Allen Poe, Jules Verne, but particularly H. G. Wells.

The

Second Era:

Modern Science Fiction

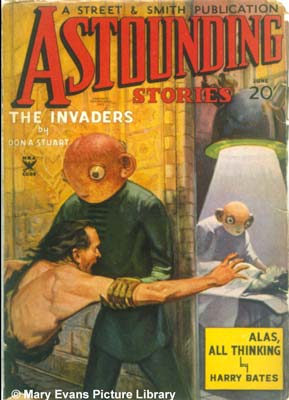

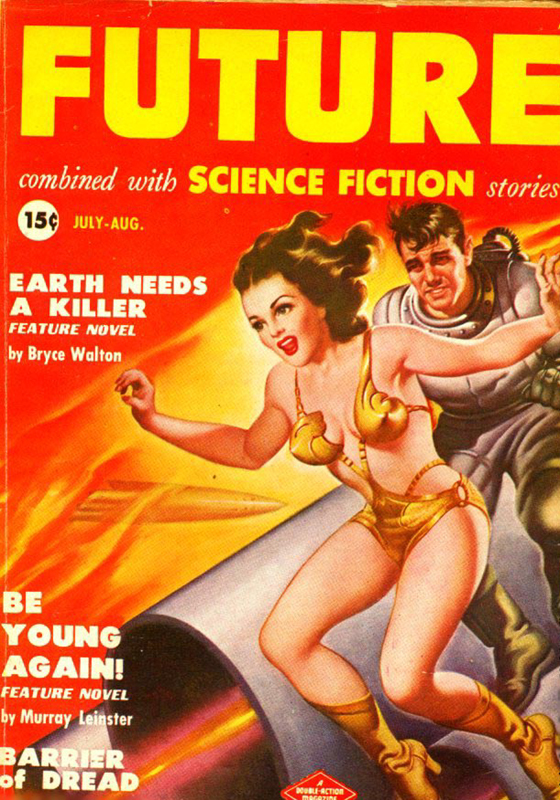

The era of modern science fiction begins in 1937 when John W. Campbell Jr. takes the helm of Astounding Stories and changed the field forever. The modern era will see science fiction, under Campbell's influence, become the genre that we know today.

|

|

|

|---|

T

The

Third Era:

Contemporary Science Fiction

The contemporary era begins approximately when Harlan Ellison publishes his landmark anthology Dangerous Visions in 1967. (This is a date that I have chosen because so much of science fiction is different after Dangerous Visions came out.) At the same time, in England, Michael Moorcock takes over as editor of the radical mag New Worlds and allows all manner of experimentation. And somewhere in there, this new kind of writing is called the New Wave. This New Wave was led by writers and editors who had sensed a kind of stagnation in the field and felt that the field needed a change, a booster shot, a kick in the ass.

The New Wave in science fiction was devoted to publishing stories that broke all sorts of boundaries, that defied every accepted (and expected) publishing convention. Not only did these writers write about sex and morality in new and startling ways, they also sought to break all sorts of narrative modes, such as writing stories where the timeline is all screwed up ("Terminal Beach" by J. G. Ballard is a good example of this), or stories where actual computer tape is infused in the text, as in Harlan Ellison's "I Have No Mouth And I Must Scream." In fact, this was a time when everything in our culture changed. And it changed forever.

***

Science fiction as it exists today is a worldwide cultural phenomenon that encompasses both the printed word and visual media. It even has tropes and conceits in found in advertising and music videos. There have even been science fiction plays, such as Karl Capek's R.U.R. in 1920, which gave the world the word "robot" for the first time, and operas such as Karl-Berger Blomdahl's Aniara (1959), based on a 1953 epic poem by Swedish poet Harry Martinson (who eventually won the Nobel Prize in Literature) about a starship lost in space. All kinds of science fiction archetypes and modes of storytelling permeate our day-to-day experiences.

Scene from the opera Aniara.

We are, in fact, living in the future. To a person alive, say in 1909, just about every aspect of our lives would seem very futuristic and very strange, yet ordinary reality--reality as we see it--is literally nothing to us. Most of us are so caught up in our personal and private affairs that we don't think of time at all. Most of the time, our lives are so mundane as to become nearly boring.

Yet, another way of looking at "now" is to see it as the past, the dim past, to those not yet born (your children, your grandchildren). Imagine them decades from now trying to wrap their minds around notions such as "MTV " or what they think of Brittany Spears or Kanye West. To them, if these people and institutions are remembered at all, they'll be seen as anachronisims, quaint manifestations of a bygone era. Do you know who Arthur Godrey was? How about Pinky Lee or Bix Beiderbecke?

Our culture 100 years from now might not exist. America could be Muslim or Mexican. It could be mostly Chinese. Who says "America" will always be what we, now, think of as American? (Odds are it will. Italy hasn't changed since the Middle Ages, nor has England. Rome is gone, though. So who know?)

Today, as a global culture, we are so used to change we almost expect it. To be sure, we demand that our art always be new and Madison Avenue is there to inculcate change so that we will always be hungering for new products with new gizmos.

But it wasn't always this way. There wasn't always a Microsoft or iPods or cell phones or talking tatoos or cities on the moon . . . .

More than just a few critics and writers have said that science fiction is the literature of change. But there was a time in history when change happened very slowly, if at all. For millennia, the word "progress" was a term that had no real meaning. Many critics have gone to great lengths to show how science fiction, they believe, was being written as far back as Plato's time or the time of the Roman poet Lucian (115-200 C.E.). Others suggest that science fiction goes as far back as the Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh. Some have suggested that science fiction might have gotten its start when humans first conceived of time, and in the case of Gilgamesh this would be Time Past. Human recognition of "deep time" might have started very early on in the evolution of civilization.

And it doesn't stop with the epic of Gilgamesh. We have stories of utopian societies (Plato's Republic gets cited the most) and the speculations of Lucian in his True History (ca. 150 C.E.). True History, in fact, is often credited with being the first interplanetary satire. And it's thanks to Plato that we have the myth of Atlantis which may also have been a psychic manifestation of the Greeks of Plato's time conceptualizing the earliest time of Mediterranean civilization.

And, indeed, there have been earlier "flights of fancy" writings, mostly in the form of "dreams" visited upon the writer. This was particularly true in a culture that had little knowledge of machines. One such story was written by an Englishman, Francis Godwin. Godwin wrote A Trip to the Moone in 1638, a combination of two books of dreams.

Godwin was a British prelate and church historian and A Trip to the Moone, a mostly secular work, went through at least 27 editions, mostly because it was intelligently written. A Trip to the Moone was very popular in its time and was translated into several languages and read across Europe.

On the heels of Godwin's "flight of fancy" came one from the Cyrano de Bergerac Savinien, he of the large nose and a taste for dueling. Voyages to the Sun and the Moon came out in 1662 and only seemed to cement the French eccentric's penchant for flagrant idiocy. The Frenchman in question did not mind, however. He relished the attention.

In his tale, de Bergerac suggested that one might fly by trapping dew in bottles, strapping the bottles to oneself, and standing in sunlight. So it wasn't as if humans in the Renaissance and Enlightenment period were without imagination.

These works, however, are not predictive; they are not seen as happening in the future; nor are they about the effects of industry, science, and invention.

Moreover, they are all couched in the present moment of each writer's time. Rarely do they come from a perception of change induced by technological growth on their culture. Lucian's True History is a satire on modes of belief common to his own time. He knew nothing about the future. The same is true of Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels, written in 1726. Gulliver's Travels is satire, not a document born future shock. Even the prophecies in the Bible reflect the time during which they were written. We see no futuristic cities in the visions of John of Patma. This is because they knew of no change. Their tomorrow would be just like their yesterday. Nnot ours.

So we can say that science fiction is (at the very least) a form of literature that is consciously aware of change, particularly change coming from the dual impacts of science and technology on our lives. Thus we only get true science fiction when Industrial Revolution in England begins in the middle of the eighteenth century. Up to that point, people had no real concept of the future because they had no concept of material progress---progress they could see and upon which they could extrapolate consequential events in their lives---perhaps not on a daily basis, or even a yearly basis. But people in England in the early 1800s could see it happen with decades. The world of Browning and Tennyson is vastly different than that of Wordsworth and Shelley.

This change in time-perception really began around the time of the Protestant Reformation in 1517 C.E. This was also the era of the great European explorations of the oceans. News of strange lands, strange animals, and strange peoples began to trickle into Europe. Add to this the earlier invention of printing in Germany (ca. 1440 C.E.) and you get a cultural revolution that creates an influx of (and a desire for) information about the world beyond one's humble village.

So what is "science fiction"? There are hoards of excellent definitions, but the definition I want to work with is this:

Science fiction is an expression in literature of an author's sense of dread based on perceived or imagined changes in society brought about by science and technology since the time of the Industrial Revolution.

The definition above isn't unique to me. You can find similar characterizations of SF if you go to:

***

Brian Aldiss, in his The Trillion Year Spree, believes science fiction is a subgenre of literature in the Gothic mode. Specifically, he says: "Science fiction is the search for a definition of mankind and his status in the universe which will stand in our advanced but confused state of knowledge (science), and is characteristically cast in the Gothic or post-Gothic mode" (p. 26). Thus, many science fiction stories border on the horror story archetype: the monster coming back to haunt us, a monster right out of Europe in the the Middle Ages, the Golem.

If not the Golem, we have the homunculus, a man-made creature found most notably in Geothe's Faust. In Faust it's mostly a play-thing of the troubled genius, but Faust does not turn his miniature creation loose on humanity. Like Dr. Frankenstein, he creates it simply because he can.

Some critics, notably Ursula K. Le Guin, has suggested that science fiction is a specific kind of literature mostly recognizable by its images, icons and tropes. These would be things like robots, alien beings, ray guns, etc. that undeniably ground a story in a science fictional universe or science fiction milieu.However, what would not be part of the science fiction realm would be elements of "mythic" icons, such as those representing Good and Evil and archetypes more commonly found in the works of Joseph Campbell and Carl Jung. These are the predominant elements of the Star Wars stories, for example. George Lucas was a student of Campbell as Campbell was a student of Carl Jung. Thus no one schooled in the history of science fiction would see Star Wars as anything but fantasy, or perhaps a Western that takes place in outer space instead of the American west. Star Wars may have science fiction icons, but the series is more loosely characterized as fantasy than science fiction. But let me be clear here: This is not to suggest that Star Wars is somehow diminished by the above characterization. Star Wars is intrinsically faithful to its own tropes and icons and is a whole hell of a lot of fun besides. Everything a good science fiction adventure should be. (And, yes, incomplete sentences are allowed now and then.)

All this is to say that we have to be careful when we are making wholesale claims for "proper" science fiction icons. Tom Wolfe's book,The Right Stuff, has all kinds of futuristic icons, not the least of which are astronauts and real space ships. However, you can't characterize movies such as 12 Monkeys, Gattaca, Minority Report, or District 9 as anything but science fiction. It's a question, in the end, of how the icons are used and how the extrapolations of advanced technologies are depicted.

By our definition, true science fiction appeared when people began to get a sense, however murky and ill-defined, that some aspect of their lives was being subtly influenced by changes in their culture.

However, critic John J. Pierce suggests that science fiction actually evolved from the travelogue or the tale of a journey to a faraway land, both real and imagined. Pierce points to the writings of the ancient Greeks and Romans (such as Lucian) and to stories where men flew to the moon with wings or rode in saddles attached to giant birds or just got there in their dreams.

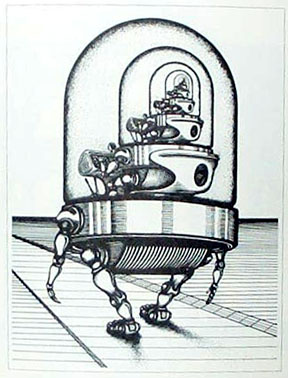

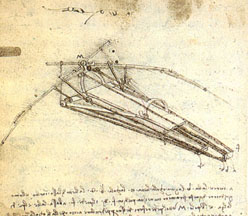

This da Vinci illustration resembles a winged re-entry space vehicle. Do you think he knew something?

Indeed, for two thousand years world literature was rife with familiar tales of fantastic journeys, so much so that all Jules Verne had to do was tap into an already present interest in the travel literature genre.

Jules Verne, however, used real science, or science as he understood it, when he conjured the strange vehicles his protagonists used. This is what made Jules Verne, in John R. Pierce's view, the first science fiction writer. Verne's characters go to the moon, travel around the world and under the sea. They even journey to the center of the earth. This is the essence of science fiction: humankind's ability to alter their destinies through technology. The wrinkle in most science fiction stories is that these technologies often transcend our ability to control them.

Here we need to pay attention to Brian Aldiss' notion that science fiction is a subspecies of Gothic fiction. There is something very important going on in Mary Shelley's "ghost story" Frankenstein that is often missing from the stories of Jules Verne. Mary Shelley managed to instill familiar (to her time) Gothic elements of the mysterious, exotic, and unknown into her tale, a tale that still haunts us. The Gothic sensibility brings to science fiction the emotional aspect of the nightmare-made-manifest. (Wait until you read Jerome Bixby's story "It's a Good Life.") Frankenstein occurs at a time when the consequences of a technological wonder are only just beginning to be perceived, and dimly at that. When it happens, though, all hell breaks loose: The good doctor has created this thing, but then what? The monster, it turns out, has a few ideas of his own, such as having a wife and raising a family, or perhaps terrorizing the neighborhood. There are all kinds of ways that scientific advances can go wrong.

So now, let the games begin. Good luck and have fun with your new head.