|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

The Lonely Journey from Oaxaca Mexico

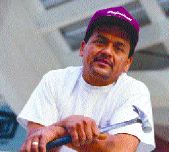

For the past year I have lived in the Renaissance apartment building, located just east of my school, Arizona State University West campus. The seemingly invisible and behind the scenes maintenance man greets every resident with a warm and inviting smile has a very interesting story to tell on how he migrated to this country. His name is Fernando and he is an immigrant from the beautiful Mexican State of Oaxaca. He is a short man in stature that carries with him a big heart and a truly remarkable take on life. For this assignment Dr. Koptiuch wanted us to interview an immigrant that has migrated here to the United States. Capitalizing on this assignment I thought it would be a great idea to get to know Fernando and to tell his truly remarkable story. The interview I conducted with Fernando was done in English in the courtyard of our apartment complex. The story he told me was filled with heartbreak, hope and compassion. Unfortunately stories like Fernando are not that uncommon but what makes him and others like him so fascinating too talk with is their unshakable will to survive and make the best out of their situations. A True Mans Man.

As he continued his story, he told me how truly different and alone he felt. He described it as being a little child “nino” not knowing how to take care of himself in this new and foreign land. Luckily for him, he explains that he knew how “to build things.” Back in his hometown, Fernando was a carpenter and as we continued our conversation, I asked him why he couldn’t stay in Mexico? He told me that he could not make enough money in Mitla to support his family. “I was a tradesmen within the field of carpentry, however when I did have a trade [work] to do sometime [s] I didn’t get money.” He also went on to tell me how dangerous it was in his hometown to be a carpenter. What he meant by this is that the same safety regulations that are taken for granted by carpenters in this country do not apply in Mexico. The example for this that he gave me was of his older brother Miguel. As he continued he once again looked me straight in the eye and told me how his brother died while roofing a new office building in the city of Oaxaca. This revelation by Fernando floored me, and I can assure you nothing was lost in translation. As he continued, he spoke of his brother’s three kids and his widowed wife. He told me how between him and his other two brothers they were able to support their deceased brothers’ family. After this heart opening revelation by Fernado, the two of us sat and perhaps reflected in our own way on the story he just told. The silent reflection period felt like five minutes, but in reality it was more like a minute. As I tried to gain my composure, I asked him how he is able to support his family. He told me that he works this job as a maintenance man during the week and he has another job installing drywall on the weekends. All the money that he earns from both jobs is sent back home to his wife and children. Fernando sends his money back through a major North American banking firm. I found this interesting because I was always under the assumption that you needed to be citizen in order to open up a bank account in this country. Rather, Fernando told me he just simply walked into the bank and asked for a Spanish-speaking banker. From there the banker helped Fernando establish a bank account and also showed him how his wife in Mexico can receive the money he puts into the account. The banker not only showed him how to transfer money to his wife in Mitla but apparently according to Fernando, the bank sent a debit card to his wife. The

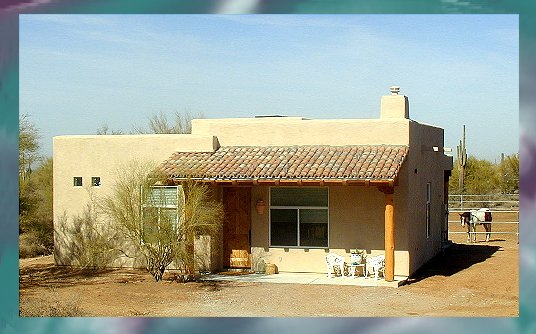

money that Fernando makes here in America may seem modest in terms

of our culture and how we view living comfortably, but for him it is

more then enough to support his family back in Mexico. During

Fernando’s last visit home more than two years ago, he finally

finished building his home. Modest, in comparison to homes here in

America, but for Fernando this truly was a monumental accomplishment

for him and his family. He showed me a picture of the home and he

told me that it cost him around 7,000 dollars to complete. $7,000

doesn’t sound like a lot, but for him it took nearly five years to

save the money up. As we began to wrap up our conversation, I asked him if he was going to return home for good. He responded with a reluctant nod and shrug of the shoulders and by saying “that he hopes he can return home and live with his family, but you know this is all just a dream…a mans job is to provide for his family and for me the only way I can provide is to stay in America… I don’t like it but that is the way it is.” Sadly this is the case for millions of so called “illegal immigrants” that come to America to work. The bitter sweet ability to earn money in America has lead to an ever increasing number of “Illegal immigrants” that come to this country in order to provide for there family. THE OAXACA CONNECTION

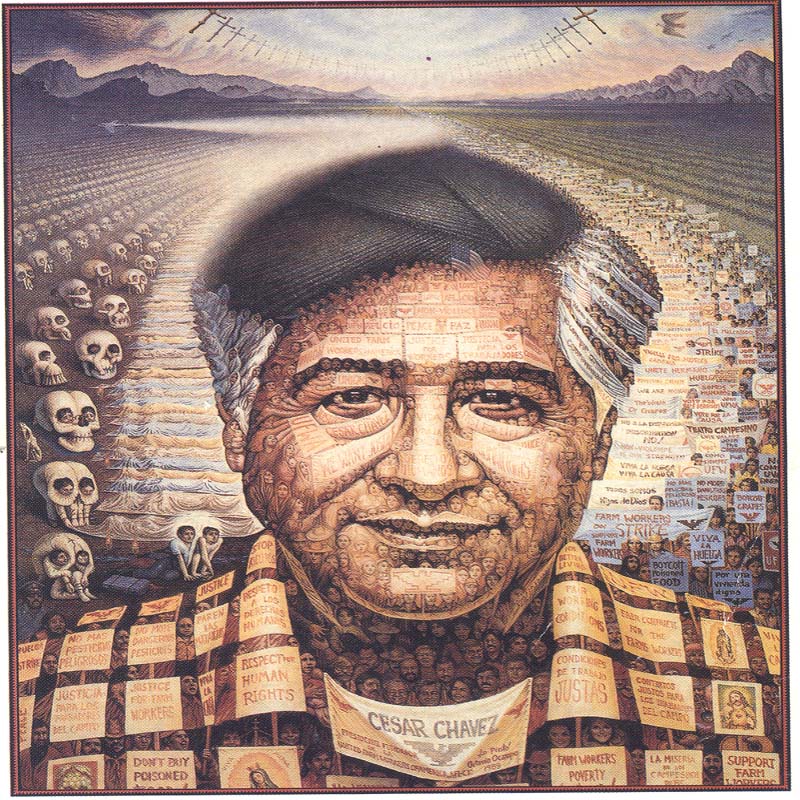

Migration of Oaxacan’s into the US is fairly low. According to, INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas Geografía e Informática and translated by Jeffery Cohen) Oaxaca ranks 16th in regards to the amount of immigrants that migrate to the United States. Of those Oaxcans like Fernando that chose to migrate, 91.2 percent remain within Mexico’s national borders and 8.8 percent, roughly 7,439 individuals crossed into another country (INEGI). Current migration in the central Valleys of Oaxaca, Mexico is motivated by real and apparent needs of migrants to send money back to their households. Like Fernando and his family the need for economic stability drives him and thousands like him out of their homeland in search of work. More often than not, the decision to migrate follows one of two paths. Either stays internally in Mexico or as in Fernando’s case look towards the North/el norte. Destinations within Mexico include urban centers like Mexico City, wherein earnings type of work is typically available, or to the northern border and state of Baja California, where work in agriculture can be found. Destinations of migrants that chose to leave Mexico for the US include Southern California, primarily the Los Angeles area and also north to Illinois, primarily Chicago. Current migration patterns of Oaxacans are deeply rooted in the past. Migrants from the central valleys Oaxaca have been leaving for the United State as early as the 1940’s and many found contract work through the Bracero Program. The

Bracero Program (1942 through 1964) was an agreement between the

U.S. and Mexican governments that permitted Mexican citizens to take

temporary agricultural work in the United States. This managed

migration, an unprecedented and radical solution to America's labor

needs, was prompted by the enormous manpower shortage created by

World War II. Over the program's 22-year lifespan more than 4.5

million Mexican citizens were legally hired for work in the United

States, primarily in Texas and California. Mexican peasants,

desperate for paid work, were willing to take farm jobs at wages

scorned by most Americans, who had moved into the better-paid war

industries. The Bracero Program helped establish what became a

common migration pattern: Mexican citizens entering the U.S. for

work, going home to Mexico for some time, and returning again to the

U.S. to earn more money, the so-called 'circular migration pattern'

of workers between Mexico and the U.S. The Bracero Program may have brought many Mexicans to this country during its twenty-two year existence. However do to the continual economic crises and political uncertainty that continues to plaque Mexico. Many Oxacans chose to migrate in order to find the elusive economic freedom they all are searching for. By the year 2000, according to Jeffery Cohen in his book The Culture of Migration in Southern Mexico, Oaxacans are well represented in the migrant stream heading for the US. According to the data provided by http://www.migrationinformation.org - on average, 46 percent of a central valley community's households included at least one migrant (see Table A)However migrants like Fernando from Oaxaca still remain a relatively small percentage of migrants living and working in the US (about 4 percent).

Oaxacan migrants settled with family or friends once in the

US (87 percent lived with a relative or friend), in southern

California; the Los Angeles-Santa Monica area is home to 94 percent

of the central valley's migrants. Sixty-two percent found work in

the region's service sector, mainly in restaurants, small

businesses, and homes.

To understand migration and remittance practices in Oaxaca's central valleys, a random sample of 15 percent of households in 11 communities was selected. In total, data for 590 households was collected, of which a little less than half had direct experience with migration. Source: Cohen, Jeffery, the culture of migration in Southern Mexico, 2004. Remittances typically went to daily and household-related expenses, with 60 percent covering immediate household expenses, construction and renovation). Other expenses include education, the purchase of appliances and domestic goods, and health care. Daily costs of living ranged from the purchase of food to payments for utilities (electricity, gas, and firewood). Many interviewees suggested that using remittances to cover daily expenses was a waste of hard-earned cash, but given the lack of local jobs, most argued there were few alternatives (see Table B).

The amount of Oxacans that migrate to the US is fairly small with comparison to other Mexican states. The remittance that they send home plays a large and significant role in the economic well being of their families and of course the general overall economy. Oaxacans like Fernando play a significant role in the international economy and of course the State Of Oaxaca. The ambition and foresight of Migrants like Fernando keep our economy as well as theirs running. Hopefully the information that I have provided for you will give you a better understanding on the issue of migration. The next time you see an immigrant on the street hopefully you will remember the story of Fernando, the heartbreak and truly extraordinary life that men and women like him lead. Sources for this Section:

Cohen, Jeffrey H (2004). The

Culture of Migration in Southern Mexico. Austin: University of

Texas Press.

Migration Information Source. (May2006). Fresh Thought, Authoritative Data, Global Reach. http://www.migrationinformation.org United Farm workers (January, 2006). http://www.ufw.org

COMMENTARY:

SELECTED FACTS ABOUT MIGRATION TO THE US Via And Beyond Mexico

· According to the U.S. Census bureau, the foreign-born population of the United States is currently 33.1 million, equal to 11.5 percent of the U.S. population.

· Out of this total, the U.S. Census bureau estimates that 8-9 million are illegal immigrants.

· The US Census Bureau's American Community Survey, estimates that there were 9.9 million foreign born from Mexico in the United States in 2002.

· Between 1990 and 2000, the number of foreign born from Mexico in the United States more than doubled. The foreign-born population from Mexico increased from 4.3 million in 1990 to 9.2 million in 2000, or by 4.9 million persons, according to the results of Census 2000. The Mexican immigrant population more than doubled in size, increasing by 114 percent over the decade.

· Mexico continues to be the leading source of unauthorized immigration into the United States. According to a January 2003 report published by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), Mexico was the leading source of unauthorized immigration into the United States in the 1990s. The INS estimates that the unauthorized resident population from Mexico increased from about two million in 1990 to 4.8 million in 2000. By January 2000, Mexico accounted for nearly 69 percent of the total unauthorized resident population. The INS estimates also suggest that in 2000 over half of all Mexican foreign born were undocumented.

·

Census Bureau.

(April 14, 2006). Estimates of race/ethnicity. Retrieved April 27,

2006, from: www.census.gov.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The

first question I asked of Fernando was to describe his journey to

the United States. As he started to explain he looked directly into

my eyes and told me of the difficulties he had in his long trip up

from Oaxaca Mexico. Fernando in 1999, at the age of 22 left his

hometown of Mitla with his two older brothers and his younger

cousin. The four of them left behind their oldest brother Miguel,

parents and grand parents. In Fernando’s case he left his newly wed

bride and one year old baby girl Maria. As he continued his story a

bitter sweet smile came over his face as he explained to me how they

took long bus rides, slept along road side’s, eating and drinking

whatever they could get their hands on. The four of them crossed

the border illegally and for understandable reasons Fernando chose

not to elaborate on this matter. When the four of them arrived into

the country they had only one contact. The contact was a man from

their town that had made the journey a little over a year ago.

The

first question I asked of Fernando was to describe his journey to

the United States. As he started to explain he looked directly into

my eyes and told me of the difficulties he had in his long trip up

from Oaxaca Mexico. Fernando in 1999, at the age of 22 left his

hometown of Mitla with his two older brothers and his younger

cousin. The four of them left behind their oldest brother Miguel,

parents and grand parents. In Fernando’s case he left his newly wed

bride and one year old baby girl Maria. As he continued his story a

bitter sweet smile came over his face as he explained to me how they

took long bus rides, slept along road side’s, eating and drinking

whatever they could get their hands on. The four of them crossed

the border illegally and for understandable reasons Fernando chose

not to elaborate on this matter. When the four of them arrived into

the country they had only one contact. The contact was a man from

their town that had made the journey a little over a year ago.

Unfortunately

stories like Fernando’s are not that uncommon. For generations now

scores of Mexican men have been embarking on similar treks as

Fernando’s, which have brought them here to the United States. The

reasons for why these men risk so much can be answered in a simple

five-letter word M-O-N-E-Y. Many Mexicans like Fernando have to

make a hard choice of whether to stay in their country and suffer

from poverty or risk everything by crossing into America illegally

in order to find work. The subsequent facts listed below will help

better illustrate the ever increasing number of people like Fernando

that are willing to risk it all for the love of their family.

Unfortunately

stories like Fernando’s are not that uncommon. For generations now

scores of Mexican men have been embarking on similar treks as

Fernando’s, which have brought them here to the United States. The

reasons for why these men risk so much can be answered in a simple

five-letter word M-O-N-E-Y. Many Mexicans like Fernando have to

make a hard choice of whether to stay in their country and suffer

from poverty or risk everything by crossing into America illegally

in order to find work. The subsequent facts listed below will help

better illustrate the ever increasing number of people like Fernando

that are willing to risk it all for the love of their family.